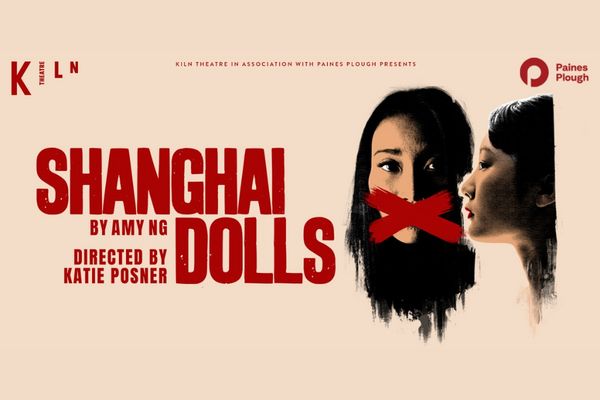

Review: SHANGHAI DOLLS, Kiln Theatre

Two women rise to power in postwar China.

![]() Looking at the rise and fall of two powerful Chinese women through the vague lens of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House probably sounded good on paper. It’s a shame then that Shanghai Dolls fails to deliver on almost every front.

Looking at the rise and fall of two powerful Chinese women through the vague lens of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll House probably sounded good on paper. It’s a shame then that Shanghai Dolls fails to deliver on almost every front.

Amy Ng’s new play begins in 1930s China as a starving teenager we will come to know as Sun Weishi (Millicent Wong) stumbles into a theatre where the future Jiang Qing (Gabby Wong) is practicing lines for the role of Nora. The first will go on to be adopted by Zhou Enlai (second in the country only to Chairman Mao) and become the country’s first woman director. The second ends up as Mao’s wife, starting the Cultural Revolution that will imprison and kill Weishi.

In this war torn country as the Nationalists fight a savage war against the communists, the two begin from very different places. Weishi is the daughter of a Communist martyr and part of with deep political connections. In contrast, Qing comes from a much poorer background. She and her mother ran away from their violent father and, as she trains to be an actress, her mother is working as a domestic servant who occasionally “warms” the master of the house’s bed. While Qing disdains the “champagne” leftists around her, Weishi is more of an establishment creature who leans on her “uncle” Zhou for help. Despite these differences, they move in together and pledge loyalty to each other.

From there, the story jerks forward in jumps and hops. Famine and civil war are followed by the rise to power of Mao and, much later on, the inevitable backlash against the old guard in the form of the Cultural Revolution. Qing finds herself replacing the Chairman’s first wife but, as a consequence of her new position, is forced to give up politics for 30 years.

Weishi, meanwhile, is sexually assaulted by Mao who buys her silence through a position high in the theatre world. These Noras have moved on from the early confines but find their position and “freedom” once again defined and bounded by the men around them.

That Ng is a historian is clear from the wealth of exposition delivered in each scene through news articles projected onto the walls and set design. Her love for this period shines through but - even will all the information splashed up and dotted into the dialogue - it is still hard work to grasp the nuances of the bigger picture as we move along.

Time passes in an Interstellar-style fashion: tens of years pass on stage in what is a few minutes for us. There’s some effort to “age up” the characters through direction or clothing as they go from youth to middle-age but not enough to help us adjust to the rapid shift along the timelines and keep our empathy for their respective plights.

Director Katie Posner keeps the pedal to the metal in a play that was commissioned during the Covid-19 pandemic by ex-Kiln artistic director Indhu Rubasingham before her move to The National Theatre. Its long gestation hasn’t paid off in terms of enabling this play to find its voice with its clunky script not allowing the characters to breathe to any great extent.

The final climactic scene between Weishi and Qing is truly gripping. It shows a greater focus on drama and more potential than anything in the hour beforehand and highlights how much of a missed opportunity Shanghai Dolls really is.

Shanghai Dolls continues at the Kiln Theatre until 10 May

Photo credit: Marc Brenner