Review: THE OUTSIDERS at Dr. Phillips Center For The Performing Arts

The Outsiders still does what it’s always done best: remind us that being young is hard, being different is harder, and that found family can be the thing that saves you.

It’s hard to overstate just how much The Outsiders changed everything. S.E. Hinton started writing the novel when she was only sixteen years old, partly as a response to her own dissatisfaction at teen-targeted fiction that, essentially, did not take teenagers seriously. By the time she published it at nineteen, she had unknowingly created the Young Adult literary genre as we know it today: for-us, by-us stories about young people that didn’t talk down to them. The Outsiders was unfiltered, emotional honest, and hard-edged where it needed to be. It told readers, particularly adolescent ones: you were allowed to be angry, it’s okay to be scared, there is admiration in loyalty. Teenagers were allowed to, at least in fiction, be human. Nearly every YA novel that followed owes something to Hinton’s decision to tell the truth about adolescence instead of sanitizing it.

That truth is what drew Francis Ford Coppola to the story nearly two decades later. Prompted by an middle school class who petitioned him to adapt the novel into a film, Coppola’s 1983 movie introduced the Greasers and Socs to a cinematic audience. The initial theatrical cut came with, unfortunately, quite a few compromises that Coppola though would make the film more appealing: much of the first third of the book was condensed, emotional beats were rushed, and the ending arrived before the story’s full resolution could land. Coppola himself later admitted the film didn’t quite reflect the novel’s scope or heart. More than twenty years later, he returned to the material with The Outsiders: The Complete Novel, a director’s cut that restored nearly a half-hour of deleted scenes to reshape the film into an experience far closer to Hinton’s original vision.

The leap from page and screen to stage took even longer. The Outsiders as a musical was first announced in 2019, only to be delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic before it ever had a chance to find its footing. A workshop followed in 2022, before premiering at La Jolla Playhouse in 2023, making the jump to Broadway later that year. It became clear that this was not a novelty adaptation looking to cash in on IP familiarity with the Coppola film, but a serious piece of musical theater. Like the Coppola film, the stage musical was remarkably faithful to Hinton’s written text, while taking liberties that allowed this new approach feel earned and original. The folk-rock score, kinetic choreography, and emotionally grounded storytelling struck a chord with audiences and critics alike as the production went on to win multiple Tony Awards, including Best Musical, thus cementing its place not just as a successful adaptation, but as a legitimate continuation of The Outsiders legacy.

Now, that legacy is on the road with a national tour that launched this fall, bringing the Tony-winning production to cities across the country. For the next week, Orlando, Florida gets to call it home. For longtime fans, it’s a chance to see a familiar story reframed in a New Medium; for newcomers, it’s a powerful introduction to a world that has been resonating for nearly sixty years. However you come to it – be it the 1967 book, the 1983 movie, or the 2023 musical – The Outsiders still does what it’s always done best: remind us that being young is hard, being different is harder, and that found family can be the thing that saves you.

Act I opens with Ponyboy Curtis (Nolan White) anchoring us in memory and place, situating the audience firmly in his version of the world (“Tulsa ’67”). What follows is the Greasers’ loud, joyful self-definition of their social class: a full-throated celebration of loyalty, bravado, and belonging (“Grease Got a Hold”). But almost immediately, the show pulls us inward, narrowing its focus to the Curtis household, where identity is less about swagger and more about responsibility. Darrel Curtis (Travis Roy Rogers) steps forward as both brother and stand-in parent, mourning the life he might have had while doing his best to keep what remains intact (“Runs in the Family”). From the outset, the musical establishes its central tension: Ponyboy is still figuring out who he is, while Darry has already been forced to decide who he must be, with middle brother Sodapop (Corbin Drew Ross) caught between them, smoothing edges and absorbing the fallout.

As Ponyboy moves through the world, his idealism becomes both his strength and his liability. He believes, sometimes stubbornly, that people can be more than the sides they’re assigned, a worldview crystallized in a late-night, hopeful reflection (“Great Expectations”). A night at the drive-in introduces Ponyboy to Cherry Valance (Emma Hearn), and while their conversation briefly softens the Greaser/Soc divide, it also deepens Ponyboy’s sense of being misunderstood at home. His connection with Cherry is marked not by romance so much as recognition, given voice in the tender, searching duet (“I Could Talk to You All Night”). Meanwhile, the strain inside the Curtis family intensifies. Darry’s fear for Ponyboy sharpens into control, Ponyboy bristles against it, and Sodapop once again finds himself acting as the emotional glue, even as the cracks widen.

The act pivots when Ponyboy and his Best Friend Johnny Cade (Christian Arredondo) muse about escaping from Tulsa for another town and another life (“Far Away From Tulsa”). The idea of escape surfaces not as freedom, but as loss, as it underscores just how deeply Ponyboy’s identity is tied to his family. An unfortunate run-in with Cherry’s boyfriend Bob (Mark Doyle) ends in violence that comes quickly and irrevocably, leaving Johnny and Ponyboy with no option but to run. Their friend Dallas (Tyler Jordan Wesley) helps them plan their midnight escape, while Darry and Sodapop are left behind to reckon with fear, guilt, and the possibility that love may not be enough to keep a family together. The act closes with motion rather than resolution, as flight becomes both literal and emotional (“Run Run Brother”). The Curtis brothers thus become separated, but still bound: a reminder that this story isn’t about who throws the hardest punch, but about what it costs to protect the people you love.

One of the most effective things the musical gains by moving from page to screen to stage is permission to reframe the story without betraying it. By leaning harder into the Curtis brothers as the emotional spine, the musical clarifies a distinction that’s always been present in the text but rarely foregrounded this explicitly: Darry, Soda, and Ponyboy are family by blood, bound by obligation and grief; while the Greasers are family by choice, bound by loyalty and survival. That distinction gives the show room to deepen Ponyboy’s relationship with Johnny in particular. Their closeness isn’t new – it’s consistent across the novel, the Coppola film, and now the musical – but onstage it feels more fully realized, less rushed than in the 1983 film, where the faster-paced momentum and runtime sometimes flattened quieter emotional beats. Here, Johnny isn’t just Ponyboy’s friend or fellow runaway; he’s the person who understands him most clearly, and the one relationship that bridges both kinds of family at once.

The stage musical also makes a bold – and, some might argue, overdue – choice to lean into the LGBTQ readings that have long surrounded The Outsiders, even if S.E. Hinton herself never intended the characters to be read as queer. Decades of interpretation, helped along by the inescapable homoerotic charge of Coppola’s film, have already cracked that door wide open. The musical merely steps through it with a confidence that might have been seen as controversial even ten years ago. This doesn’t mean the musical is relabeling characters or rewriting the text. Rather, it’s allowing the intensity of these homosocial bonds to exist without a “No Homo” preface or apology. Nowhere is this clearer than in “Far Away From Tulsa,” a song that plays less like a simple escape fantasy and more like an “I Want” anthem for queer youth who know, deep down, that the life they want isn’t available where they are. Lyrics about a place that feels real even if it hasn’t been seen yet, about being free to decide who you want to be, and about choosing each other as family practically invite a queer reading – and one that resonates powerfully on a Broadway stage filled with young bodies singing about futures they’re not yet allowed to claim. In a way, the musical doesn’t rewrite Hinton’s The Outsiders so much as it listens more closely to what it’s been saying all along about the strong bonds of friendship.

Dayna Taymor’s direction of The Outsiders, working from a libretto by Adam Rapp and Justin Levine (who also co-wrote the score), gives the musical one of its most quietly radical strengths: a distinctly female gaze on masculinity. Like Hinton before her, Taymor isn’t interested in sanding the boys down or turning them “soft” in a way that feels corrective or ironic. She’s not “fixing” them to her liking. Instead, she treats their softness as intrinsic to their masculinity, not in opposition to it. These Greasers are, in many ways, the softboi archetype before the term ever existed: outwardly rough, defensive, and posturing, but inwardly tender, loyal, and deeply emotional. The direction consistently allows space for that contradiction to exist without a raised eyebrow or a sly wink to the audience. These boys are genuine in their emotion, they’re allowed to feel them and perform them. They cry, cling to each other, yearn, and dream, even as they perform toughness for the world watching them. And while the show never turns into a lecture about gender, it is unmistakably shaped by it: it takes women like Hinton and Taymor to look at men not as problems to be fixed, but as people whose vulnerability is not a flaw. In doing so, the musical offers something rare: not a critique of masculinity, but a vision of what healthy masculinity can actually look like when it’s allowed to be honest.

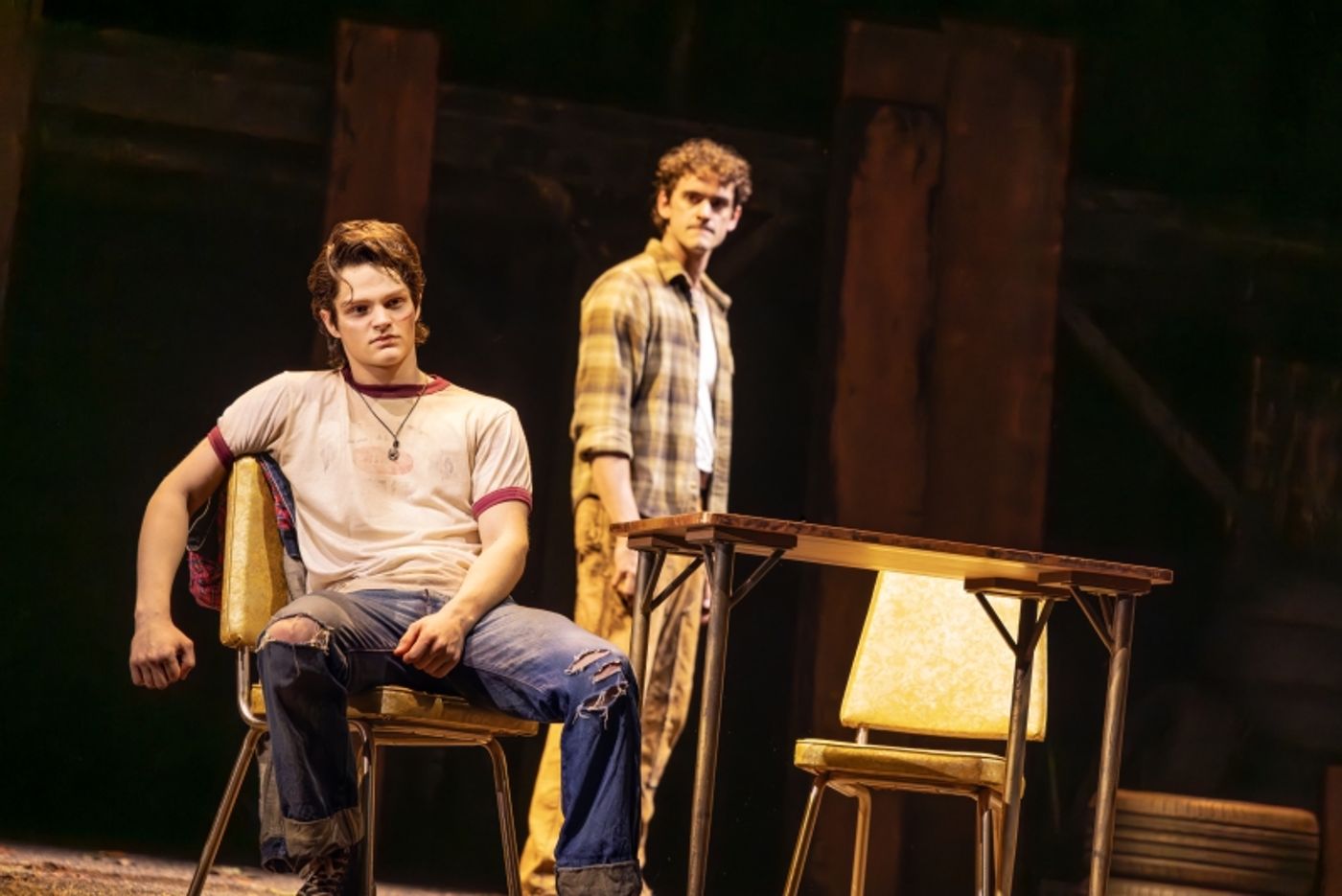

As a result of Taymor’s direction, the cast themselves are doing extraordinary work across the board. At the center of it all is Ponyboy Curtis, played by Nolan White, who is effectively the engine of the entire show. He’s onstage for what feels like ninety percent of the runtime, and at no point does he ever step outside the character. Not even before the show officially begins, when he’s already seated among the audience, quietly inhabiting Ponyboy’s interior world. That level of sustained focus would be impressive for any performer, let alone one so young. Ponyboy is meant to be fourteen; White is, I believe, around twenty, and the gap never shows. He brings a depth to the role that balances teenage angst with a sense of premature world-weariness, as if Ponyboy has already lived a little too much life before he’s had the chance to be a kid. It’s a demanding performance, both physically and emotionally, and White carries it without a single visible crack.

That emotional weight lands even harder because of the work being done by the other two Curtis brothers. Travis Roy Rogers plays Darrel as if he’s wandered in from A Doll’s House, and I mean that as the highest possible compliment. There’s an Ibsen-esque seriousness to his performance: a sense that every line is being filtered through years of internalized responsibility and suppressed grief. Rogers treats Darry’s struggle not as melodrama, but as lived reality, relying as much on restraint as on outward expression. It’s a choice that could feel out of place in a musical, but here it grounds the entire family dynamic, giving Darry’s authority real emotional stakes. Watching Rogers work, you believe completely in the cost of being the brother who had to grow up first.

That intensity is beautifully counterbalanced by Corbin Drew Ross as Sodapop, the emotional core of the Curtis family and the connective tissue between his brothers. Sodapop has always been the heart and soul of the story (an assessment Ponyboy gives time and again in text, film, and musical). Ross leans into that role with warmth and clarity, giving the character a depth that surpasses the famously underwritten portrayal by Rob Lowe in the 1983 film (the theatrical cut reduced Lowe to three scenes, one of which was literally just him stepping out of the shower). This Soda feels alive in every moment: open, expressive, and deeply sincere, with affection for both Darry and Ponyboy that feels instinctive rather than performative. Ross’s energy plays perfectly off Rogers’ severity and White’s angst, creating a family dynamic that feels organic and lived-in. True to the Hinton text, this Sodapop doesn’t need alcohol or rebellion to escape; he “gets drunk on just plain living,” and Ross makes that joy feel not naive, but necessary.

Johnny may not technically be the story’s lead, but emotionally, he is Ponyboy’s person whether one chooses to read that bond through a queer lens or as a brother-from-another-mother connection forged by shared neglect. In this performance, Johnny was played by swing Christian Arredondo, who delivered an achingly tragic interpretation of the role. Arredondo leans hard into Johnny’s loneliness, shaping him as a boy who was never loved enough, and whose hunger for belonging gives his attachment to Ponyboy its emotional gravity. There is something deeply endearing in the way this Johnny gravitates toward kindness wherever he finds it, and devastating in how little of it life ultimately allows him. His fate, at just sixteen years old, lands with quiet, crushing force. And if there were any doubt about how this relationship reads to a modern audience, “Far Away From Tulsa” removes it entirely. The song all but canonizes Johnny and Ponyboy as the story’s emotional center, inviting the kind of fervent audience investment that has long fueled “shipping” culture. Both “Far Away From Tulsa” and “Stay Gold” serve to position them, quite naturally, as the OTP of The Outsiders, whether the text names it or not.

And then there’s Dallas Winston. My goodness, there’s Dallas Winston. Tyler Jordan Wesley gives Dallas a presence that’s both intimidating and quietly protective, establishing him as perhaps the truest father figure in the story, even more than Darrel at times. He knows exactly when to play tough; his tense back-and-forth with Cherry at the drive-in reads less like flirtation and more like taunting, testing boundaries and daring her to push back. But when it comes to Ponyboy, Wesley dials up the gentleness, creating moments of care and protection that make Dallas’s climactic Act II number, “Little Brother,” devastating in its tragedy. If Travis Roy Rogers treats The Outsiders like an Ibsen play, Wesley is channeling August Wilson: grounded, muscular, and deeply human. The casting here is also a smart, intentional shift: while Hinton’s original Dallas is tall, blond, and blue-eyed, and Coppola famously cast teen idol Matt Dillon regardless of eye or hair color, Wesley’s Dallas is African-American, bringing new layers of depth to the role. His paternal instincts, combined with his assumed toughness, enrich the character’s relationships with Ponyboy and the rest of the Greasers, making Dallas not just feared, but truly respected and beloved.

Emma Hearn’s Cherry Valance is a masterclass in duality. In dialogue, she reads as impossibly proper – almost Stepford-level poised. At first, it’s disarming, but then it clicks: the story is filtered through Ponyboy’s recollection, and he has lionized Cherry as the embodiment of everything “good” about the Socs. Hearn leans into that, playing Cherry as if she’s in a Douglas Sirk melodrama (golly, imagine if Cherry Valance were a member of the Hadley family in Written on the Wind), with every gesture and line carrying a subtext beneath the outward perfection. And then she sings. When Cherry sings, Hearn lets the character’s real voice emerge: vulnerable, wobbly, emotionally open. It’s a subtle, remarkable choice that lets the audience hold two readings at once: we have Cherry in dialogue as a girl trapped by the expectations of wealth and privilege, and Cherry in song as someone who, in her own way, is as much an Outsider as Ponyboy. The performance reminds us that outsiderhood isn’t about leather jackets or street fights; it’s about longing, alienation, and the quiet courage to be oneself.

Adding more fuel to the Sirk Subtext fire is Mark Doyle’s Bob, who is a fascinating study in charm gone wrong. At first glance, he embodies the clean-cut, all-American It Boy — the kind of guy you’d imagine as Troy Donahue in A Summer Place or John Saxon in Rock, Pretty Baby: classically handsome, effortlessly charismatic, the type everyone would be expected to like. But Bob is, in reality, profoundly insufferable, and Doyle leans fully into that contradiction. He plays him as the mirror-universe version of that teen idol archetype, the polished exterior revealing entitlement, arrogance, and cruelty rather than virtue. It’s a delicate balance: the audience can admire the effortless charisma of Doyle while simultaneously reviling his character’s behavior. Doyle’s control over just how much of Bob’s privileged slimeballness is on display is masterful, making us loathe the character and yet enjoy watching him command the stage.

It might feel like a disservice to lump the rest of the cast together, but the ensemble and minor characters are the unsung heroes of this production: Seth Ajani, Brandon Mel Borkowsky, Dante D’Antonio, Gina Gagliano, Hannah Jennens, Giuseppe Little, Sebastian Martinez, Abby Matsusaka, Justice Moore, Mekhi Payne, John Michael Peterson, Luke Sabracos, and Jonathan Tanner. These performers are constantly switching hats – literally and figuratively – moving seamlessly between Greasers and Socs as each scene demands. A few smaller roles stand out: Jaydon Nget brings mischief and charm to Two-Bit, Katie Riedel makes Marcia memorably supportive, and Jackson Reagin gives Paul just enough presence to matter in a scene or two (particularly when his previous friendship with Darrel is revealed). Justice Moore also notably plays Ace, a prominent female greaser that joins her boys in the memorable Rumble. But more importantly, the ensemble’s ability to vanish into whichever side of the class divide is required not only highlights their versatility, it reinforces one of the show’s central ideas: that everyone, no matter their status, feels isolated at times. Their constant transformations become a kind of thematic echo, amplifying the emotional core of the story and giving the main characters’ struggles context, contrast, and resonance.

When it comes to the technical factors of this production, the lighting design in The Outsiders is nothing short of spectacular. It’s easy to see why the show won the Tony for Best Lighting Design. Here, light and shadow aren’t just decoration, they actively shape the story, mirroring both the camaraderie of friends and family and the tension between the Greasers and the Socs. The gradients and diffusers do more than simulate sunsets and sunrises; they reflect the way memory filters reality, highlighting the distinction between lived experience and recollection. Key moments are enhanced with subtle strobing or “slow-motion” effects, signaling to the audience that what we’re witnessing is Ponyboy’s memory, not objective time. The movement of the performers is only part of the choreography – lighting now dictates how we see, how we feel, and how deeply we inhabit Ponyboy’s point of view. It’s a quietly brilliant example of design shaping narrative, turning every shadow and highlight into storytelling itself.

And then there’s the Rumble. Spectacular and intimate all at once. A water dance, a symphony of movement, a 21st-century take on the dream ballet, but condensed and narratively necessary. Every punch, tumble, and pivot is meticulously choreographed, and yet it feels wild, chaotic, and utterly alive. The performers make the stage pulse with tension and adrenaline. The rainfall initially seemed like a very clever projection at first, until I noticed splashing on the set. They literally made it rain in the theatre. The audience’s reaction was immediate and instinctive. There was a silent awe as we watched this all unfold, no one dared to even cough or unwrap a noisy bag of candy. Then at the conclusion, applause erupted before the lights even went down. A few theatergoers almost gave a premature standing ovation, thinking the show had reached its climax. The Rumble is not just a fight scene; it’s a kinetic expression of brotherhood, rivalry, and youthful bravado, distilled into pure spectacle. If a single number could clinch a Best Musical Tony on its own, the Rumble is the one that did it for The Outsiders. Watching it is like being inside the story itself: thrilling, dangerous, and impossible to forget.

The Outsiders on stage is more than an adaptation; it’s a full-throttle reimagining that honors S.E. Hinton’s original novel while taking full advantage of the musical medium. Every element works in concert to make the story feel lived-in, as if pages from the book itself were directly imagined on the stage. Whether it be Dayna Taymor’s sensitive, female-gazed direction or the powerhouse performances by the cast, The Outsiders never loses sight of its emotional truth: family by blood and family by choice are one and the same. The musical doesn’t just retell Ponyboy’s story; it immerses the audience in his world. In the shaky dynamics of the grieving Curtis brothers, in the heartbreak and humor of adolescence and friendship. It’s a production that wholly respects its roots while boldly carving out new ground, whether that’s leaning into the depth of Johnny and Ponyboy’s bond, exploring masculinity through a female lens, or turning a fight scene into a moment of pure theatrical magic. By the final note, it’s clear that this version of The Outsiders isn’t just a nostalgic revival or a high-concept curiosity. Rather, it’s a landmark production for modern theatre, one that is fated to continue to resonate for the foreseeable future as its source material has done for the last sixty years.

THE OUTSIDERS plays at Dr. Phillips Center December 16 through 23. Tickets can be acquired online or at the box office, pending availability.

Reader Reviews

Videos