Review: ANGELS IN AMERICA, PART TWO: PERESTROIKA at Theater West End

For all the heaviness and turmoil that Millennium Approaches gives us, Perestroika somehow manages to find a levity to make us find the joy in life.

Previously, on Angels in America:

Based on statistics available from the Center of Disease Control, from May 1991 to November 1992, roughly 47,892 people passed away due to AIDS-related illness. Breaking that down even further, that meant about 2,660 people a month would die. On the daily, that’s 88 folks per day. 88 heartbeats stopped. 88 lives cut off. 88 stories now unfinished. There’s a beautiful irony in that statistic, though. 88 also represents the idea of double infinity, a seemingly neverending concept. And so those 88 souls per day, those 2,660 names per month, those 47,892 individuals that passed across a year and a half… they go on forever. As do those before and after them. Their light may have dimmed, but the fact that they shone at all means something. It meant they were here. It meant the shadow of their former presence is now taken care of by others. After all, those 88 people did not live within a vacuum. Each one of them was connected to others: survivors, family, friends, the occasional passing glance across a crowded room. The impact of 88 people per day is, in truth, that double infinity. And those 88 people, the abstract idea of them growing exponentially every day, lives forever.

Why, specifically though, am I focusing on a statistic of May 1991 to November 1992? Quite simply, because that’s how long it took before Angels in America, Part Two: Perestroika made its stage debut. Writing about this play thirty-five years later means I have the benefit of immediacy. I didn’t have to wait eighteen months for the “tune in tomorrow…” of it all. On the contrary, it was a mere eighteen days between the closing of Part One and the opening of Part Two at Theater West End. And yet, I couldn’t help but think now about those 47,892 people — whoever they may have been — that Angels in America did not reach in time. To those people, Angels in America remained unfinished. No opportunity to see a resolution. No chance to learn what the Great Work might have been, or if Prior would also succumb to his illness, or how deep Joe and Louis’s affair would go. The mystery of what’s next that keeps audiences on the edge of their seats at the end of Millennium Approaches gets resolved as Perestroika plays out.

And it somehow manages to be a superior story to its predecessor. For all the heaviness and turmoil that Millennium Approaches gives us, Perestroika somehow manages to find a levity to make us find the joy in life. We are already familiar with these characters, we’ve cried for them before. Now, ironically, we get to laugh with them, too. Make no mistake, this isn’t some side-splitting, stomach-clutching, farcical comedy of errors. Rather, it’s a smartly-written approach to allow for humor to help off-set the pathos. For lines to be allowed to be funny. For characters to embrace certain absurdities because, at this point in life, you may as well enjoy what time you have. That, perhaps, is what helps make Perestroika stronger than Millennium Approaches. We are allowed to take a breath, to no longer gasp and wince at the inhumanity of a disease, but instead to applaud the perseverance of those who still fight with it. We are meant to question the ambiguity of Prior’s visits with the Angel just as we are meant to enjoy the bending of reality as implausible connections between six desperate people bring them together in New York City to have an appointment with destiny.

The singular line “My ex-lover’s lover’s Mormon mother” alone is a prime example of why Perestroika surpasses the sheer genius already found in Millennium Approaches. It shows just how interconnected each character is to the other, a microcosm of the entire population of New York City itself. Through this cognitive bias of identifiable victim effect, the audience now can know those 88 people per day who will never have known Perestroika. Any of them may have been a Prior or a Belize or a Joe or a Harper. They may have known a Louis or a Hannah or an Angel itself. They may have been wronged by Roy. But what those 88 people, per day, now have is a vague understanding — even 35 years later — that their story was allowed to be told.

Part Two: Perestroika begins with a preface from the world’s oldest living Bolshevik, Aleksii Antedilluvianovich Prelapsarianov, who urges then-President Mikhail Gorbachev to walk back the various progressive reforms he was introducing to the country. Gorbachev, a polarizing figure in Russian politics, became a key figure in lifting the Iron Curtain between the Soviet Union and the Western world, even if it came at the cost of the dissolution of the USSR in December 1991. Aleksii decries progress, believing the only way forward is by looking back: return to the old ways, regress to what (didn’t) work before. This scene, while seemingly inconsequential to the personal lives of the other characters we already know, sets forth the thesis of Perestroika — both the play’s title and the actual, political movement set forth by Gorbachev. Unlike Millennium Approaches, where every character’s life is upended by the AIDS epidemic and their connection to it, Perestroika seeks to restructure these lives and force them to move forward. They cannot go back to what life was before, making a compelling argument as the three acts play out: it’s not even a question if they can go back, but also if they even should. After all, there’s no turning back in a world that will move on with or without you.

Meanwhile, Prior (Ben Gaetanos) and Belize (Zoa Starlight Glows) are leaving a funeral when Prior recounts to Belize the encounter with the Angel (Ame Livingston). The Angel instructed Prior to retrieve a book underneath a tile in his kitchen, while also giving him a vision of Heaven: a city not unlike San Francisco, created by God. God had, in 1906, abandoned Heaven for Earth because He was enamored by the continued progress mankind had made. Their ability to choose, to copulate, to change, had enticed God as the Angels were incapable of changing or creating themselves. The Angels hope that Prior might become their prophet, to tell the world to stop — literally, figuratively, and every definition in between — so that God might then return to Heaven. Belize is unsure whether to believe Prior’s vision, theorizing it could simply be an elaborate hallucination Prior has created to cope with his illness and physical decline.

When Prior goes to a Mormon center to research more about angels, he meets both Hannah Pitt (Janine Papin) and Harper Pitt (Lauren Elizabeth Reed) — unaware of their connections to Louis via Joe. Neither Harper nor Prior remember each other from their previous hallucinations, although they do have a sense of recognition. At an animatronic display of a Mormon family, Harper jokes that the father reminds her of Joe (Celestino De Cicco), who suddenly gets into a spirited argument with Louis (Jeffrey Correia) about Joe’s religious upbringing. Joe later visits a dying Roy at the hospital, where he receives a blessing from him, although Roy gets incensed upon learning Joe has left his wife Harper to live with a man. He urges Joe to reconcile with Harper, which they do, but both realize whatever love they might have shared between each other could never be intimate. Prior and Belize decide to find Joe and confront him about being with Louis. Belize recognizes Joe from his visit to Roy’s, and now discloses to Louis the true nature of Roy’s hospitalization. Gradually, more and more interconnected moments continue between these characters — leading to the unexpected Hannah Pitt at Prior’s bedside when he takes a turn for the worse, while Joe and Louis have an acrimonious break-up, and Harper leaves the city entirely for parts unknown.

At that point, the rotating stage — which had been turning counterclockwise for all of Millennium Approaches and Perestroika — suddenly made a half-turn clockwise, which was the wrong direction compared to how the stage was meant to turn. It shut down the show for a second. At least, that’s what we were led to believe. Instead, when the lights came on, we were no longer in New York City, but in Heaven as the Angels all argued with each other about the upcoming Chernobyl disaster, as well as the arrival of the Angel with their prophet Prior. Whether or not he becomes the prophet they want is their great question, as well as the culmination of the Great Work they have given him.

Theater West End was wise to split Angels in America in the season as two separate performances, each with their own block in the schedule. Originally, I was concerned that the Part Two of it all might turn away prospective theatergoers. But upon watching both parts now, and bearing in mind my own familiarity for the characters, I can also see now how the original production’s 18-month gap would have also been enticing for an audience. Perestroika does immediately continue the story threads of Millennium Approaches, but also offers enough context within its own libretto to stand firmly on its own. Very few sequels — in theatre or cinema or television — have that “standalone” capability, but Angels in America somehow makes it work. Yes, you should still have sought out Millennium Approaches when it was playing. But Perestroika takes the foundation of that and says, “what direction can we go now?” without ever being fully reliant on its predecessor. It forces the audiences to play catch-up to the characters themselves, always moving forward with the momentum of the story and each character’s journey. Even the effective “one-minute recap” that Theater West End posted is sufficient enough for a newcomer to Perestroika to enjoy the play without having seen Millennium Approaches.

Part and parcel of why Perestroika seems to work as a standalone is in the fact that, tonally, it allows itself to lean more into the suspected supernaturalness of the Angels. It bends time and space with breaking the fourth wall — not for the audience, but for the characters — with hallucinations and visions and clearly improbable scenes that give them information they wouldn’t have gleaned through real-world, natural means. Much of the hallucinations we saw in Millennium Approaches were often attributed to the drugs (valium for Harper, various medications for Prior). Here, other characters participate in the hallucinations to now suggest that they may not be hallucinations after all. That the Angels may be among us after all. That Prior’s role as “prophet” is not a coping mechanism, but something beyond even his own understanding. Perestroika works because it’s not bound to the dictates of traditional theatre. It encourages the surreal, it embraces a stagecraft that reminds audiences they’re watching a story. It forces that audience to rethink what they saw and find new meaning in it. Most importantly, it does so while still delivering performances that make these characters relatable.

Hunter Rogers continues his direction he brought to Millennium Approaches, now joined by stage manager/sound designer/projection designer Bryan Jager as his co-director. Jager himself even has a very minor role during the scene in Heaven, which I found to be very clever. It read initially as “Oops, a tech issue, let’s hold” before I realized that it was entirely intentional and helped make the surreality of Perestroika even more genius. As both were on hand for Millennium Approaches, they bring their same sensibilities to Perestroika. Likewise, much of the crew is the same, so set design, costumes, lighting, all are consistent with Millennium Approaches. We are literally within the same theatre space, allowing for a sense of familiarity where both plays are definitively presented as parts of a whole. And even if it was a few weeks between Part One and Part Two, knowing that the same theatre company of players were behind it allowed viewers to never feel like Perestroika was trying to distance itself from its predecessor. As a result, Rogers and Jager, as well as the crew they oversaw, were able to guide the entire production into a narrative through line that allowed Perestroika to definitely stand out on its own even if it is, by all traditional definitions, a sequel.

In particular, I felt that the two were able to guide the performers — also already familiar with their own characters — into more naturalized delivery. A dialogue-dense play like Angels in America might sometimes fall into the trap of sounding preachy — as if the words spoken were meant for the unseen audience rather than for another character — but Kushner knows how to give this dialogue flavor, to make it apparent that these characters are talking to each other, audience be damned. As a result, Rogers and Jager are able to finesse within the performers that absolute dismissal of the audience themselves. They don’t hold for applause or offer any winking nod at a one-liner that ate in rehearsals. They’re able to ensure the performers remain in their world, while allow us as an audience to observe it from our carefully-calibrated distance.

In particular, Celestino De Cicco’s Joe feels the most natural on that stage. His mic knocked out for the first hour or so of opening night, but he never overcompensated by yelling his lines. If anything, the faulty tech made him feel much more natural than intended. His delivery and his portrayal of the character, someone who’s growing vastly different from who he was in Millennium Approaches, made him the standout in my opinion. His Joe has the most ties to each character on the stage, which necessitates different approaches as well based on who he’s with. The concern I had for the underdevelopment of Harper in Millennium Approaches is somewhat resolved in Perestroika. Harper’s got more of a backbone in this half of the play, with Lauren Elizabeth Reed now delivering a character who’s less kooky and more nuanced when it comes to the forced progress she must make: the life she wanted and was groomed for has been taken away, the entire world is a blank slate that’s hers for the taking. Ultimately, I still feel like Harper is underwritten, but at least her projected arc when viewed in full context of Millennium Approaches and Perestroika makes more sense now.

Surprisingly, Joe’s mother Hannah gets much more development in Perestroika than she did in Millennium Approaches, for which I was grateful. Janine Papin helps make the character fully realized, as Hannah herself even addresses that her particular demographic — conservative, religious mother — is an unfair stereotype just as Prior’s — an out and proud gay man — also can be. The unexpected friendship between Hannah and Prior becomes a welcome turning point for both characters, establishing a new sense of the “found family” that often results from LGBTQ community’s clashes with more conservative groups. I was grateful to see it played as sincere and genuine, rather than a camp approach of the “f*g hag” and her gay-best-friend. Ben Gaetanos’ Prior throughout Perestroika also has a more charged, “I Want to Live!” sensibility that allows Prior to also feel much more grounded than he had been in Millennium Approaches. Even when he’s afforded an amusing one-liner, it’s given within a serious context that allows the line to feel potent without overreaching. His two notable sequences with Angel America, played by Ame Livingston, also allows the latter to finally delve more into who this mysterious character is and how she relates to the others on stage.

The new character coupling of Hannah and Prior also leads to a more unexpected pair of scenes between Louis and Belize that brings forth new history between them, Prior, and Joe. As a result, it allows Jeffrey Correia and Zoa Starlight Glows to really dig deep into the neuroses of their characters, the shared history between them, and the present-day concerns that keep them inextricably tied together. The moment between the two in Roy’s hospital room — with the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg also present — serves to show that same interconnectedness between characters that otherwise might have never met before. Roy, too, still played by Thomas Muniz, becomes much more humbling of a figure. Muniz brings great sympathy to the role, as the book itself does what it can to make the audience feel sadness for the real-life figure’s demise. Death doesn’t discriminate the way we do, though. It came for Cohn in the summer of 1986 even after he strong armed his vast connections to put him on AZT treatment — despite the fact that countless more patients could have benefited from the clinical trials he co-opted for his own health. If any tears must be shed for Cohn, it is shed more for the humanizing treatment he was given in Angels in America.

And, in the end, it’s really the Human Factor of it all that makes Angels in America such a powerful presence within the greater purview of American Theatre. In spite of its supernatural, meta, and reality-bending approach to the AIDS crisis, the focus has always been on that tiny little subset of people and how we relate to them. How we relate to the abandonment, to the loneliness, to the closet. How we feel about spirituality, about organized religion, about our morals versus our actions. Angels in America, both parts but especially Perestroika, asks more of its audience because it knows it’s living on borrowed time. Millennium Approaches hooks the audience in, offering a strong foundation of characters and narrative that makes them want to come back for Part Two. Perestroika clutches to the audience, even knowing that eventually, they must let them go. Our time spent with these characters, with their moments in time, with their trials and tribulations and twist and turns, must come to an end. We will likely never see an Angels in America, Part Three. But we don’t need to.

Maybe that’s the quiet miracle of it all. Those 88 people per day I wrote about at the beginning — those stopped heartbeats, those unfinished stories — they serve to remind us that history is not an abstraction. It is not a statistic on a CDC report or a footnote in a theatre program. It is people. It is Prior standing at a fountain insisting on more life. It is Harper boarding a plane toward an unknown future. It is Belize refusing to let cruelty have the final word. It is Joe, and Hannah, and Louis, and even Roy, each confronting who they have been and who they might yet become. Perestroika does not resurrect the 47,892 souls lost in that eighteen-month waiting period. It cannot rewind the clock or return what was taken. But it does something perhaps more enduring: it insists that these characters’ stories — and the stories of the 88 who followed the next day, and the next — are folded into a larger, double-infinity of human connection. “The Great Work” is not about stopping progress, nor about returning to some imagined past. It is about continuing. About remembering. About allowing the light that once shone to refract through us. And so, even as the curtain falls, even as we leave the theatre and the rotating stage finally rests, those 88 lives — multiplied across years and decades — do not feel unfinished anymore. They feel carried forward, weaved into the tapestry of unwritten tomorrows by our own design.

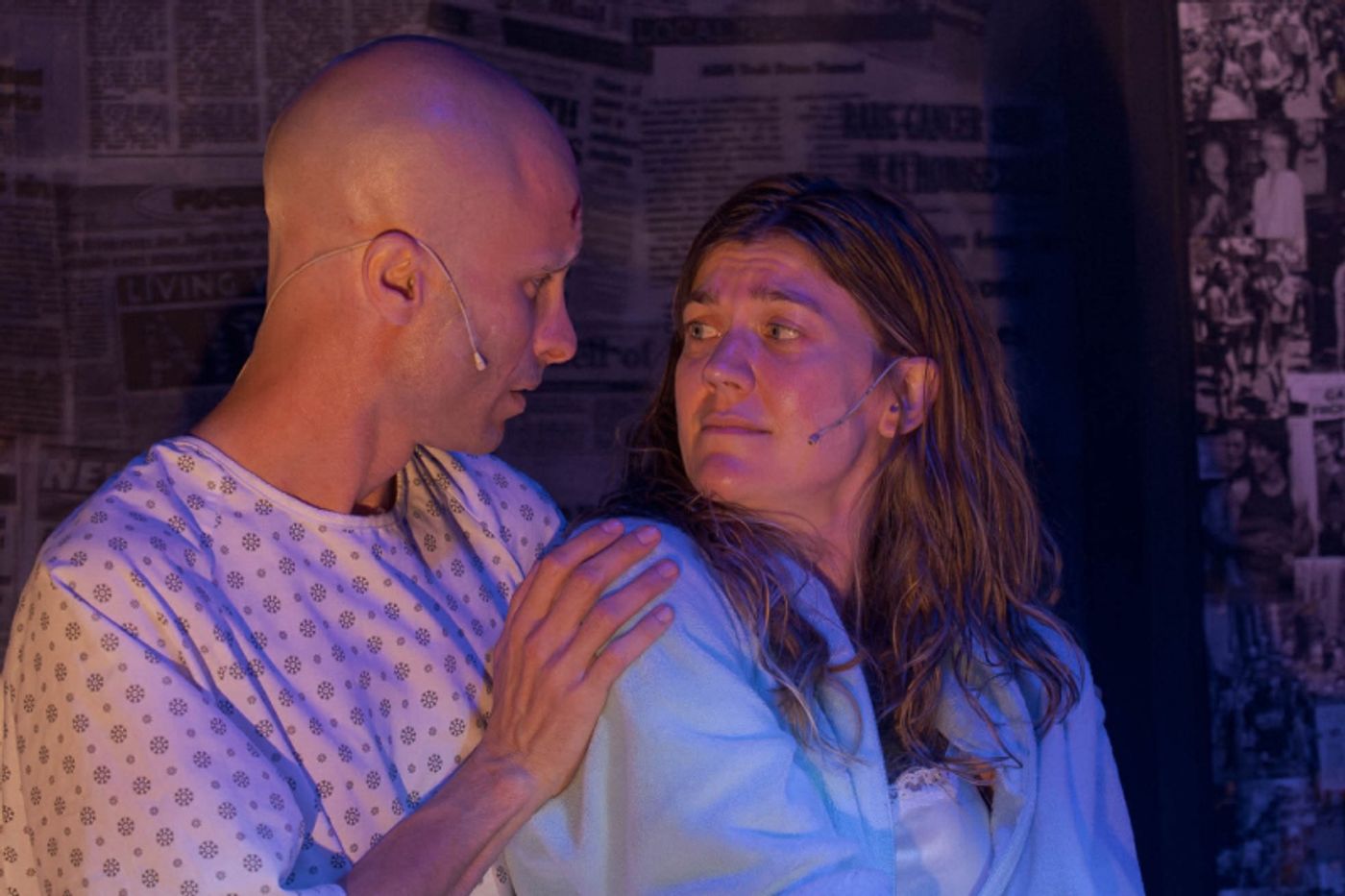

Angels in America, Part Two: Perestroika plays at Theater West End February 20 through March 8. A special one-day performance of both Millennium Approaches and Perestroika back-to-back will occur on March 7. Tickets can be acquired online or at the box office, pending availability. Photography by Red Front Door Studios, used with permission.

Reader Reviews

Videos