Student Blog: Being Black in the Art-o-Sphere

What Being Black in the Arts Means, Depicts and Is

Being a person of Black-American descent and being in the arts has helped me understand myself and my identity within an artistic space throughout these past couple of years. From art pioneers like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Katherine Dunham, Eartha Kitt, Aretha Franklin, Alvin Ailey all the way to Andre Leon Talley and Sean Bankhead, their influence in pop culture has shaped the way we perceive art and what we draw a liking to. Black creatives are the reason why all forms of art look the way it does today. Without the pioneers in theatre, dance and TV/film, the enhancements and what we see today in all ranges of media wouldn’t exist. As much as Black culture heavily influences what we wear to the music we listen to, why is being black in art so damn hard?

One of my earliest memories when forming media literacy is realizing how some of the most popular artists at the time - Beyonce and Micheal Jackson - were people that more or less looked like me and the people I was related to, yet I had seen the oppression of Black people on a day to day basis - whether online or in person. It became very clear that the product of their labor was more celebrated than what they actually stood for as people and their communities. Black performers are less likely to be seen as people in comparison to their non-Black counterparts, due to harmful racial biases perpetrated by the viewer. Beyonce and Micheal Jackson being some of the only highly accredited Black musical artists in the past 2 decades when they are also heavily influenced by people that look like them is disturbing. Not everyone is destined for the utmost amount of fame — of course, but for their influences to be ripped of accolades to make room for mediocrity and imitation from their non-Black counterparts isn’t what makes a non-racist industry. There are specific audiences that would rather treat Black people and their art like selective things to enjoy rather than a respected community.

In circumstances more personal to me, I do know what it is like to be the only Black person in an artistic space. When I was younger and unaware of racial biases, it simply didn't affect me but as I got older, it became more and more obvious how peoples’ racial perception of others projected onto me. I can specifically recall when I was told that I could not wear tights and ballet shoes that matched my skin tone and I would have to continue wearing pink tights and shoes to maintain “uniformity.” To preface, tights and ballet shoes are pink, because they are supposed to be an extension of a dancer's line when performing and in class. The main problem with that is the color pink only matches the undertone of somebody who is White or is of a paler complexion, which excludes Black dancers and forces a eurocentric standard upon them. Being forced to wear garments that don’t match your skin tone can be mentally damaging to a young dancer, because it unfortunately teaches them that their skin tone is wrong for the kind of dance they are doing. Though my circumstances didn’t allow me to hone in on my identity, I can remember what it was like wearing garments that matched my skin tone. It was a confidence boost I didn’t know I needed. It was overall more aesthetically pleasing, as my legs and arms looked like a long, cohesive line. Since I’ve left that dance school and am fully able to wear garments that match my skin tone now, I can’t help but realize that the discrepancy was strictly racial, whether the dance school realized it or not. Not being able to wear tights and shoes that don’t match their skin tone wouldn’t ever happen to a White and/or non-Black dancer. They are already granted the confidence and the “luxury” of not having their line cut-off, therefore there is no subconscious shame for their skin color.

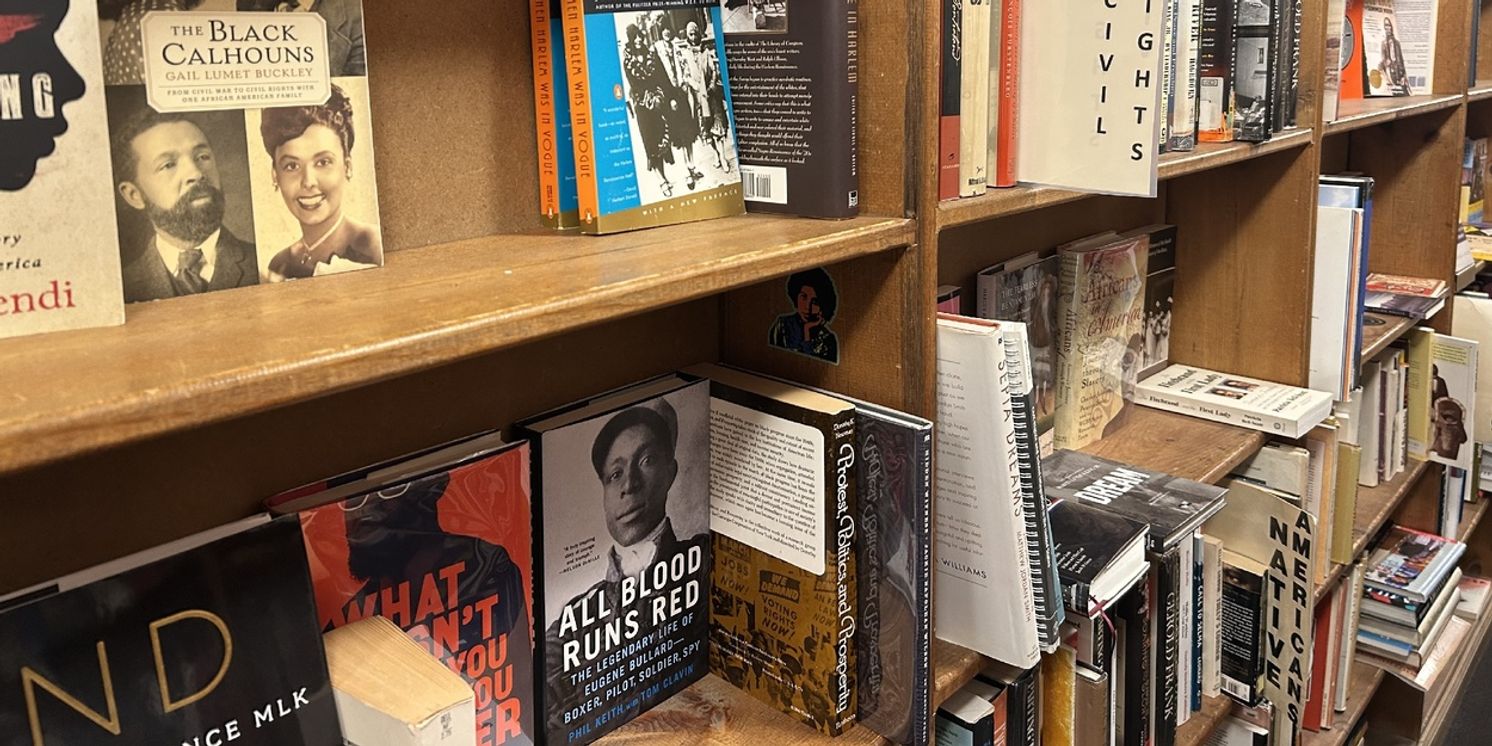

Understanding your identity within your work is just as important as creating something meaningful. Your past and whatever you make of your present and future will inevitably inspire those around us that look like us. I don’t know where I would be today without performers like Misty Copeland and Linda Celeste Sims. As tough as it is being Black in a predominantly White arts space, finding strength in my difference has allowed me to understand how important my art is. Seeing how dire art is to the world and seeing Black stories of triumph and struggle that accurately depict the Black experience is important to a young Black artists’ upbringing. One of the first times I realized how beautiful Black art is was when I watched The Wiz for the first time. I feel like it is proper to talk about now since the second Wicked movie came out, but The Wiz offers a fresh, “Black” take on the original story. The movie taking place in Harlem already adds a familiar tone to me, since my family is from there and the music hones in on the musical trends Black-Americans created in the 1900s. The beauty of the movie really shines when you recognize that all of the characters aren’t caricatures of the people who adapted the story, but an extension of their creative storytelling. My absolute favorite part of The Wiz was when the main characters stumble upon the Wicked Witch of the West’s factory and all of her workers and Mabel King sings “No Bad News”. Talk about a powerful performance! The dance number is one I’ll honestly never forget and it is still one of the reasons I want to pursue dancing on Broadway to this day. Simply put — nothing will ever compare to the cultural impact of The Wiz.

I’ve mentioned in my other blog about how going to The Ailey School for my pre-professional training has been one of the highlights of my training so far. In my senior year at The Ailey School, the Whitney Museum was displaying the Edges of Ailey exhibit and so the school got my class tickets to go. I remember walking around with my classmates talking about how stunning the exhibit was, as it meshed together the life experiences of Mr. Ailey, while highlighting his dancers and influences. There was this one video of his dancers wishing him well and telling him to get well soon, when he was dealing with complications from AIDs and I still think about that video now. The amount of love and care Mr. Ailey put into his art reflected off of his dancers — as they often got standing ovations for his work — but the community he created was one of solidarity. Mr. Ailey created a multicultural dance troupe and toured through the US during the Jim Crow era. He was daring when telling his truth and sharing stories that reflected the battles he had with himself and his identity, whilst carrying gratitude for his work and dancers. I believe that the bonds they had can only be created in such a circumstance and cannot be recreated or imitated. They were people from all different walks of life, but they knew what it was like to walk into a room and be denied service, they knew what it was like to struggle as a child, they knew what it was like to simply not understand the world around them and find refuge in dance. Every single time they performed it was a protest to tell the world that they belonged there and that their art was just as credible as any other major dance company in the world.

Being a young artist in confusing times only makes it easier to doubt myself day by day. To self-soothe, I remember all of those who came before me and how they turned their doubts and fears into something that made people like them more understood.

Videos