Review: BOOM FOR REAL: THE LATE TEENAGE YEARS OF JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT, East End Film Festival

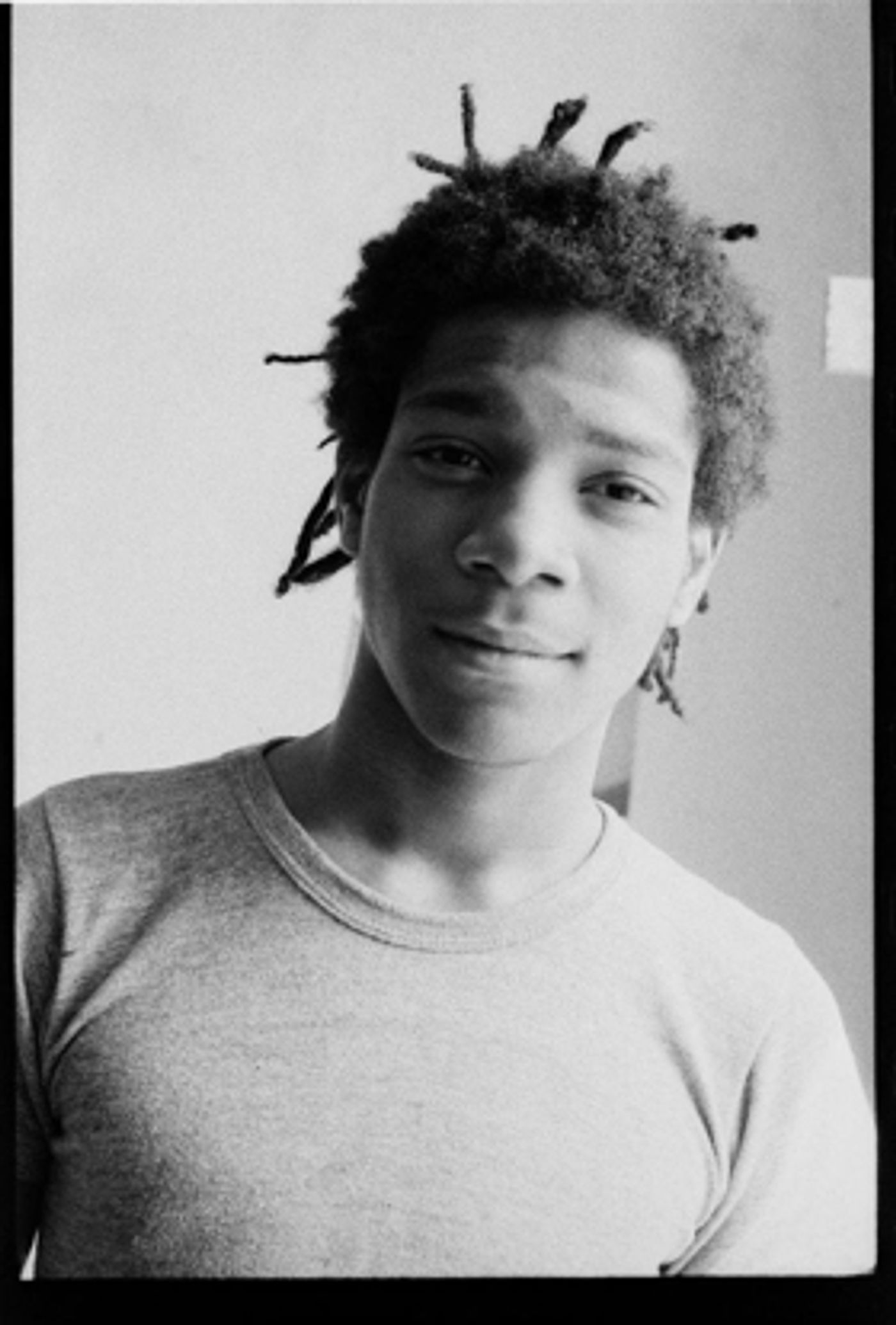

![]() Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?

Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?

I heard someone say once that all you needed for art to flourish are young people with lots of time on their hands, a bit of space in which to experiment and no money. I'd add that some - though probably not all - need a bit of talent too.

Forty years ago, Jean Michel-Basquiat and Al Diaz invented SAMO, spray-painting walls all over NYC's Lower East Side, making memes before the internet was invented - not the last time Basquiat would be ahead of his time.

SAMO, aided by the Banksyian mystery of seductive anonymity, became an underground celebrity - but bigger, much bigger, fame awaited Basquiat in a life lived with the fast-forward button pressed down very hard indeed.

Sara Driver's film shows us a late 70s New York that looks hurricane-struck. Empty streets are lined with burned-out houses, rubble is strewn along and across roads, and there just aren't any people. It's hard to believe it was like that so recently, but she was there - as I was in Liverpool, another city that teetered on the verge of bankruptcy at that time, its population diminishing, its streets abandoned... its creativity booming.

This archive footage of Basquiat and friends carrying canvases through urban desolation, smoking on stoops and graffitiing walls and subway trains because, well, you know what, they cared more for them than their owners or the authorities - these scenes transfix and lend an elegiac undertow to images of an accidental playground long gone in the real estate boom (and of playmates long lost to drugs and AIDS).

But some survived, the dice falling their way, and they're on camera, some a little ravaged (well, who wouldn't be?), but still sharp of mind and as passionate as ever about art and their long gone friend's place in its pantheon.

Fab Five Freddy has the easy articulacy of the seasoned TV star he is, telling tales of how he and Basquiat educated themselves about art. Let nobody use that damning word "primitive" about Basquiat's work - his influences may not have been hypodermically injected in a classroom, instead absorbed in museums, in conversations, in the liberating act of creation, then filtered through a consciousness that understood exactly what it all meant, right here, right now.

Jim Jarmusch gives an insight into how artistic endeavour cuts across boundaries as men and women took on roles as filmmakers, photographers, musicians, painters, collagists, performances artists, television producers... and swapped back and forth between them, the process of creation trumping the medium of production in a whirlpool of youthful energy.

Lee Quiñones talks with wonderful eloquence about his whole car works, anticipating the parkour movement, as his graffitiied subway trains transformed urban environments, putting the (hu)man back into manmade, creating a visual discourse that would inform animation, graphic design and computer games for decades. Counter-cultural work is never accepted in its time, but, at this distance, the value of the work is inarguable.

We get glimpses - perhaps more - of Basquiat the man. The slow, sometimes half-stammered speech that lends a vulnerability to offset an almost limitless internal confidence evident in his work. The face that compels one's attention, beautiful in repose yet with a ready smile could turn the lights of New York back on with its incandescence.

He may have been that friend who always seems to turn up looking for a sofa or a floor for "just a few nights" at the least convenient times; the guy at whom your girlfriend looks for just a little too long - every time she sees him; the one who smokes your dope without bringing any of his own.

But in return, you get the charisma, the talent, the sense that life will never be the same again. Artists - great artists - do not just transform the world in their art, they transform it in their presence. Driver's film makes this case slowly but irrefutably.

In a closing scene that has something of Tarkovsky's Andrei Rublev about it, the screen explodes with the mature work, the New York Times magazine cover star, the icon frozen in time by death. The paintings live on, the distillation of life in the biggest of big cities; the stories of humanity flung together, clashing and coalescing; of the potential we have - for good and for ill.

Michael Holman, whose energy seems undiminished by time, characterises Basquiat's art in terms of the man he knew, The Radiant Child, but great art always speaks with multiple voices. After over 50 years living in cities and thinking about them, how they shape people and how people shape them, I'd suggest otherwise.

One sees the hard edges, the slicing of steel lines etched across space, an aesthetic neither the product of the time and tide of natural processes, but of the urgent imperative of Man. (In this, there's something of Basquiat in Walter Hill's 1979 cult classic, The Warriors, reviewed here).

In the cavalcade of writing Basquiat draws into his paintings, one sees the chaos of communication in the city, the assault on the brain that all this information sums to, the need to continuously filter and never let up as urban space rushes towards you. Everything is fast, faster, fastest because the next thing is here already, the past layering up beneath us, informing and supporting this continuous present that won't rest.

Most of all - and this comes across much more explicitly in Driver's film than in the BBC's BAFTA nominated Basquiat - Rage to Riches, which spent too much time with art dealers and not enough with artists - one sees the depth and width of community we need simply to get through navigate the topology of life in the city.

People depend on each other not as a result of religious or family compulsion, but because to be generous is to invite generosity in return. Not everyone survives - temptation is never far away and cities might have been invented for the promotion of excess. But not everyone does (or ever did), the intoxication of life lived as blazingly bright as possible always exacting a high rate of casualties.

If you want to see what big cities were like two generations ago - and what most cities are like today - Basquiat's paintings, and Driver's film, will show you. Not always pretty - but that's life. Indeed, that's living.

Read my BWW five star review of the 2013 play about Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Andy Warhol, A Thousand Miles of History, here and my interview with its writer Harold Finley here.

Photo Credit: © Alexis Adler. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

Reader Reviews

Videos