Review: ANGELS IN AMERICA, PART ONE: MILLENNIUM APPROACHES at Theater West End

Angels in America remains one of the most important plays of the twentieth century not merely because of its intellectual or political heft, but because its realism is so emotionally precise that we recognize the people inside it.

One of my favorite films of all time is 1987’s Der Himmel über Berlin, better known to US audiences as Wings of Desire. It’s a film that takes a lot out of me emotionally, so I space out viewings of it every few years – a stark comparison to favorite films that I’d easily watch once a month or play as background noise. But once one watches Wings of Desire – uninterrupted, without scrolling a phone or checking a watch, but entirely focused on the flashing imagery on the screen – one better understands the heaviness of the film. It’s about the stark contrast between the misery of eternity and the limitless joy of being mortal. It’s about how some choices we make may not be the best choice, but the right choice. It’s about how the promise of someday will always come with a final search for tomorrow. And it’s remarkably secular despite its decidedly Biblical inspirations. Angels of Wings of Desire don’t represent any specific religion or faithfulness to a deity. Rather, they represent a longing for what we take for granted, a curse to live eternally in the periphery of life rather than actively partaking in it. And, as mentioned earlier, it takes a lot out of me emotionally anytime I watch the film.

I preface all this for the simple fact that Tony Kushner’s Angels in America is equally a very emotionally striking play that will ask a lot of its audience without ever considering if they are ready for what unfolds on the stage. And, taking inspiration from Wings of Desire, Kushner’s Angels fulfill a Watcher role – no intervention, no direct interaction until they reach that final breaking point. Whereas Wings of Desire will alternate between the miserable eternity and the euphoric mortality, Angels in America keeps us firmly planted on the ground: watching lives unfold and unravel with every turning of the earth. At the time of its 1991 debut, it was contemporary and timely, putting a raw and unfiltered face of the AIDS epidemic on stage with intensity and language that had otherwise been sanitized in more mainstream dramatic narratives (Longtime Companion, The Ryan White Story, etc.).

Angels of America today now plays as a historical time capsule of that early fear, uncertainty, and “will there even be a tomorrow?” for a disease that claimed nearly an entire generation of gay men in the prime of their lives, amidst a general public who simply were not as informed about the disease as they are now. We know now that AIDS is not transmitted by mere touch, but the 1980s treated a diagnosis as immediate social exile. It devastated communities that have never truly recovered, quite simply because there is still misinformation and assumptions out there today that it was only ever a “gay man’s disease” despite it claiming notable public figures like supermodel Gia Carangi and “Gunsmoke” actress Amanda Blake. Yet for every Gia and Amanda, there’s a Rock Hudson, a Freddie Mercury, a Joel Crothers, or an Anthony Perkins. And for every gay man, there’s also straight men like Ryan White or Roy Cohn – the latter also serving as an actual historical character within Angels in America.

Cohn, himself, never publicly acknowledged where he fell on the Kinsey Scale. For him, the identity of “homosexual” did not apply to him. A more apt description would be “men who have sex with men,” first coined in 1990 (four years after his death) as a more nuanced way to describe men who engage in intimacy with same-sex partners. Queerness never is black and white, after all, there’s no one way to “be” gay. And Cohn ascribed to an identity of power defining him, not partners. All this is to say: Angels in America treats AIDS not just as a “gay disease” but as one that’s non-discriminatory. It can happen to anyone, and the way the characters react to who it happens to defines them more than the disease could.

The two-part play begins with Part One: Millennium Approaches, which introduces us to our eight core characters and their lives between October 1985 through February 1986. Primarily, we focus on Louis Ironson (Jeffrey Correia), partner to Prior Walter (Ben Gaetanos), who has just learned he has AIDS. Louis finds he cannot cope with being by Prior’s side as his lover gets sicker and sicker, so he chooses to leave him. Prior instead finds emotional solace with friend Belize (Zoa Starlight Glows), a former drag queen turned nurse, who still hangs out with Louis – although both Belize and Louis know not to talk about Prior. Counterpoint to Louis and Prior’s story is that of Joe Pitt (Celestino De Cicco), a young Morman lawyer who’s offered a prestigious position in Washington D.C. by his mentor Roy Cohn (Thomas Muniz). Pitt, a closet homosexual who vehemently denies his attraction when Louis correctly assumes he is gay, is torn on whether or not to take the job as he must also think about his pill-popping wife Harper (Lauren Elizabeth Reed), whose addiction to Valium causes her to have hallucinations and occasionally wander off into episodes herself. One such episode has Harper believing she’s made it to Antarctica, pregnant, thanks to her travel agent Mr. Lies (Belize playing a secondary role). Roy Cohn also has learned he has AIDS by his doctor, and insists on publicly addressing it as liver cancer so as to not be associated with the stigma of AIDS being a gay man’s disease. As mentioned earlier, Roy’s identity clearly does not align with the public’s then-perception of homosexuality. He never saw himself as a pixie, a fairy, a fae, a pansy, a f****t, any slur that was commonplace then. And he surely would not want his associates to view him as such.

Despite both Roy and Prior getting sicker, Louis still cannot come to terms with his own sexuality in relation to their illnesses. A late night walk in Central Park where he failed to have a hookup later leads to him drunkenly calling his mother in Salt Lake City, confessing his orientation to a very confused Hannah Pitt (Janine Papin). She immediately sells her house so she can travel to New York to find him. When Joe finally comes out to his wife Harper, she leaves as well, causing Joe to run into Louis as they begin an affair. Prior’s sickness leads to him hearing the voice of an Angel (Ame Livingston) who tells her to prepare for her arrival, along with visions of prior “Priors” in his family bloodline – a medieval peasant and a Renaissance-era aristocrat. Roy, too, sees a vision of Ethel Rosenberg, a defendant he prosecuted and arranged for her death. And throughout all these dramatic turns, two Angels (Brenna Arden, Aryanna Lúa) stand resolute over each scene, never interacting, though often watching in judgment as to the choices of the people in the world. Part One ends with the glorious arrival of the Angel, an exciting cliffhanger that will surely see resolution – as will all these unfinished story threads – for Part Two: Perestroika.

Theater West End’s production of Angels in America is a two-part series, with Millennium Approaches running January 16 through February 1, after which a three-week (dramatic?) pause occurs, before concluding with Perestroika from February 20 through March 8. This is a change from the original Broadway mounting of the play – both parts were performed in a single day as an afternoon performance and an evening performance. Similarly, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child uses this same approach for its West End production and initial Broadway production. The Broadway version now combines both parts into one play, trimming scenes and lines and rewriting some plot points so the five-hour play now runs a shade under three. Truth be told, the emotional density of Angels in America would result in an audience being put through the wringer across over seven hours. Although I am genuinely curious and eager to watch Part Two unfold in a month’s time, I am grateful I did not have to commit to such heavy themes and contemplative questions in a single day. And I’m sure the performers, too, would need to break away from these characters and their journeys as well.

As I write that, I realize, of course, the dramatic irony of such a statement. We enter Angels in America as spectators, and the performers as re-enactors. We should consider ourselves lucky that we can “turn off” this show by the end, to walk away from it and resume our normal lives until we’re ready to return. The reality of its era meant that the glimpses of lives we see unfolding throughout the play did not have that same privilege. Men like Prior who were sick and hospital-ridden couldn’t put the disease on a shelf and walk away. Conflicted closeted characters like Joe can’t just return to his 9-to-5 until it was convenient to address his sexuality again. Even the hallucinations of Harper had an expiration date when the scene ended while those with addiction will keep suffering the withdrawal pangs. Angels in America, for all of its heaviness, should perhaps also be celebrated for allowing us the chance to step back, either at intermission or the conclusion of a Part. To give us the benefit and the clarity and that separation from the narrative. By watching this story unfold in the future that was uncertain to these characters thirty-five years ago, we owe it to their real-life inspirations and counterparts to return for the story. And to make sure the story keeps getting told.

Watching the story unfold in the thrust stage of Theater West End surely would entice any Part One viewer to immediately book their ticket for Part Two. Sanford truly has always had a gem with Theater West End living in the heart of their downtown. Their shows have consistently impressed me over the last eight years of attending productions – either as a reviewer for Broadway World or as a paying audience member – with Angels in America upping the wow factor for its approach to the material, the era, and the occasional out-there-ness of its own design. Scenes play out not just on the thrust stage, but within the aisles of the audience area. Scene changes are not done with literal sets, but a rotating stage manually pushed into place by the Angels themselves. It felt symbolic that only the Angels ever dictated these scene changes, turning the stage to watch these lives unfold scene by scene. They were the Watchers just as we were, but they had the power of choice: they choose what we see, even if they do not make choices within the world of the play. The simplicity of a door being on the left or the right side of that rotated stage helps establish the change in scenery, as do well-placed props that invite the imagination to fill in the rest of the set because the performances are so strong that they don’t require a fully physical standing set.

Co-directors Gabriel Garcia and Hunter Rogers shape Angels in America with an actor-centered sensibility that refuses to overinterpret Kushner’s already monumental text. Rather than lean into the spectacle of Kushner’s more abstract nature of the play, Garcia and Rogers manage to coax the ten-strong ensemble toward astonishingly calibrated performances – the kind that feel refined rather than rehearsed. This isn’t direction that hides behind clever scenic coups; it’s direction that trusts actors to build worlds out of tone, breath, and intention. The rhythms of New York are everywhere in the staging: impatient overlaps, clipped negotiations, acidic throwaways, tender hesitations. Scenes that are written to play back-to-back and overlap have developed a sort of quadrille approach so the audience never loses focus. All this is due to Garcia and Rogers allowing their performers to land on those micro-beats that make Kushner’s sprawling libretto feel like recognizable human speech instead of capital-T Theatre.

On the mostly abstract thrust stage, geography becomes a matter of traffic and tempo – the very New York-ness of a bustling Manhattan street gets conjured more through dialogue than through set pieces. The sterility of the hospital materializes less by its clinical design and more by how each actor functions within its space. Harper’s Valium-induced hallucinations spiral out through a loosening of gestures, with line delivery that stretches across time as if we were on the trip with them. By stripping away scenery, Theater West End’s production uses the actors’ performance as the architecture of the play, letting narrative and emotional clarity overshadow the desire for a spectacle. We have a performer-first philosophy in Angels in America that’s as revelatory as the material itself: we don’t just watch actors on a stage, we witness these characters’ lives as they know it.

Costume Designer Maria Tew leans into the play’s temporality in a way that feels slyly meta: Angels in America’s 1985 setting was contemporary enough in 1991, but all these years later now is bona fide vintage. Rather than chase an archival accuracy, Tew costumes to the way we remember the period – we have a rose-colored, VHS-graded 1980s that feels more nostalgic to our memory of the era rather than a thrift-store-find from it. There’s a wry pleasure in seeing clothes rendered not as historical fact but as archetype: Joe is the lawyer, full stop, forever encased in a Wall Street suit-and-tie uniform that reads less as menswear and more as vocation. Prior begins flamboyant and witty – the “sick gay” as the play treats him, Gloria Swanson turban and all – as he drips in theatricality that lets him pass as fine, until Tew grunges him down scene by scene as the illness asserts itself. Louis wears what one imagines an out-but-not-comfortable gay man might have chosen in 1986: sensible, slightly rumpled, studiously unremarkable, as if his body were trying not to attract attention because his partner already did. And then there’s Harper, the mysterious wife – enigmatic, hard to pin down, costumed almost as though she were walking in and out of genres rather than scenes. I still don’t have a firm grasp on who Harper is (perhaps that’s work for Part Two), but Tew’s choices suggest a woman actively resisting definition, as if her wardrobe were trying on identities she doesn’t yet believe she deserves. Must be the Mormon upbringing getting phased out of her life. The effect across the ensemble is not accuracy but affectation – the role of the costumes serve to remind us how our memory can be tender to a decade even when the subject matter is anything but.

Theater West End’s co-founder Derek Critzer is in charge of the lighting design for Angels in America. He treats lighting here less as visibility and more as its own form of dramaturgy. We don’t simply get lighting that dims on a quiet scene and brightens up for the big emotional blow-ups. Nor is it an onslaught of overhead lighting so every detail is illuminated on the thrust. Instead, Critzer brings the light closer to the body: key scenes get up-lighting from the deck so it casts faces in uneasy relief. Old-fashioned chandeliers above will flicker and hum with the nostalgia of pre-LED warmth. Temperate lighting shifts the environment strictly into the abstract, perhaps in mimicry to Kushner’s own narrative approach of overlapping scenes, characters, and hallucinations. Even when Critzer deploys a traditional spotlight, it isn’t merely to announce who is speaking, it also isolates for emotional resonance. The halo becomes narrative, evocative of the role of Angels, even among us mere mortals. In a play filled with visitations, confrontations, and observations, the dramatic choices for illumination allows us to not just see the actors, but sense their aura among each other.

Working in tandem with these performances and lighting choices is a sound design – credited to co-director Gabriel Garcia and stage manager/projection designer Bryan Jager (in regional theatre, folks wear hats upon hats) – that at long last marks a thrilling evolution for Theater West End. I still recall in the theater’s early years when the space and scope of their productions had ambition which was sometimes hampered by a dodgy soundboard and acoustics that did not do their live-orchestras any favors. Given that we are eight years and better-equipment later (and about four years since the last time I reviewed a show here), I’m glad to report that Theater West End’s sound problems are – like Angels in America – firmly in the past. We can hear Kushner’s libretto as it deserves to be heard: crisp, articulate, and unafraid of silence. Garcia and Jager balance the actors’ vocal textures with musical interludes that glide between scenes, smoothing transitions without smoothing the emotion. One moment in particular featured the dance between Prior and Louis underscored by the old standard “The Man That Got Away.” It feels very much like a thesis for their approach to the aural experience. The song doesn’t crash into the scene like a wave. It glides in gently, fading in like a warm memory taking shape. And, thus, when it finally swells, we feel caught in that same bittersweet nostalgia that the characters are reliving.

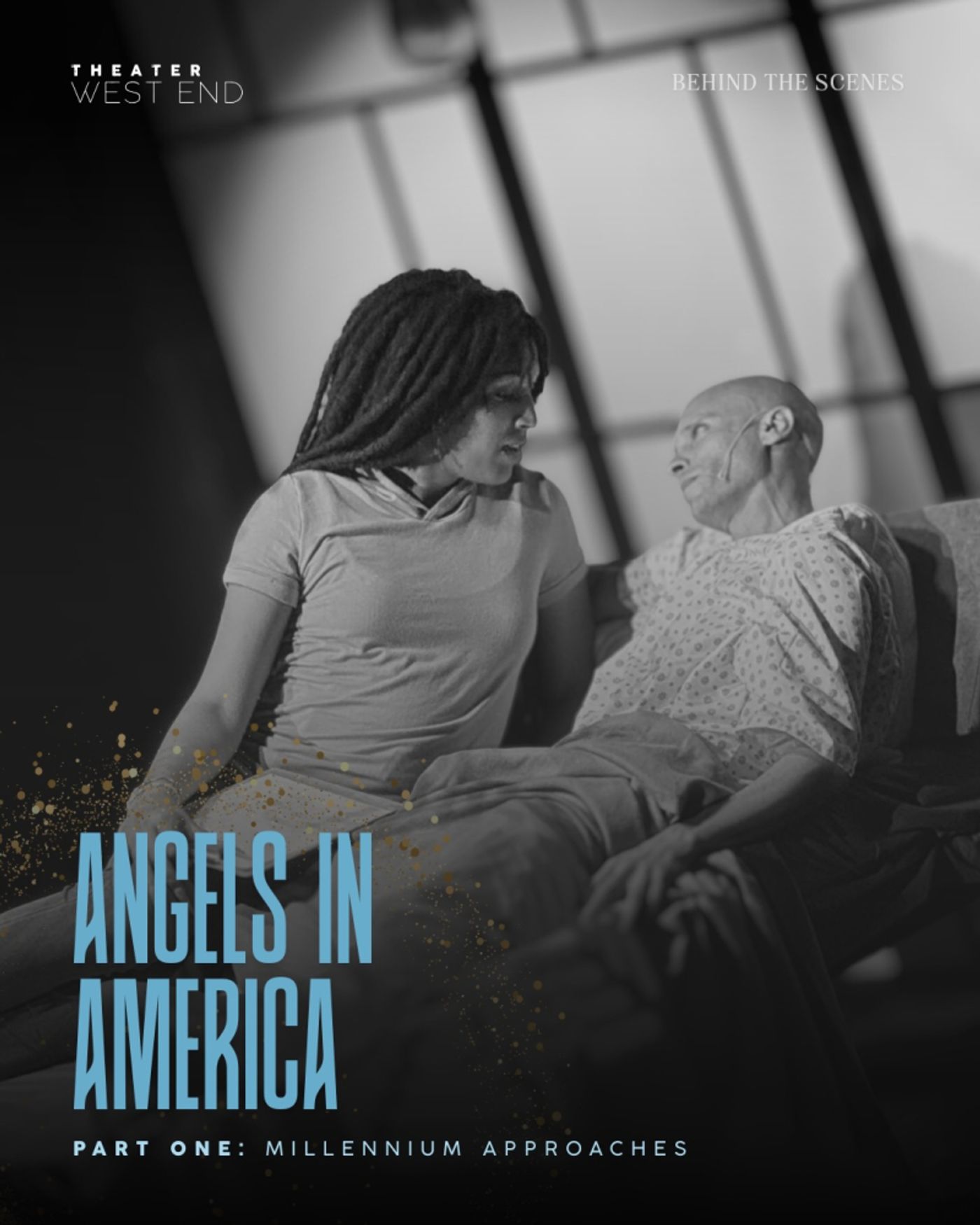

Without ever naming it, Kushner sets up Prior and Louis as the archetypal “camp gay/straight gay” couple – one is theatrical and biting, the other reserved and neurotic. Ben Gaetanos (Prior) and Jeffrey Correia (Louis) inherit that stereotype and then do something quietly brilliant with it: they play it as an old married couple. Not in the literal sense – these two characters are firmly in their mid-to-late twenties – but emotionally. Both have built a domestic shorthand into their scenes together, the kind of rhythm that only forms after years of cuddling on a couch, folding the other’s laundry, negotiating dinner plans because one wants Italian but not heavy Italian and the other just wants to eat, and waking up next to the same body. Because they establish that familiarity so effortlessly, the rupture hits harder when the play shifts from their early witty banter to the heavy stuff. Gaetanos lets Prior’s illness strip away his armor of camp until the flamboyance becomes defense, then defiance, then finally exhaustion. Correia’s Louis sputters, rambles on long diatribes, and goes off on tangents as he is unable to find the right words until the wrong ones fly out. They hurt each other because they can, because they’ve loved each other long enough to know where the nerves are. And in those scenes, the anger is so raw that even characters not in the argument react to hearing it.

Joe Pitt may not be the central focus of Angels in America – the play, by its own design, is truly an ensemble piece – but he’s the character most entangled in everyone else’s story. Celestino De Cicco leans into that cross-circuitry as he plays Joe as a man who can’t keep his identities from colliding. His Joe at work opposite Roy is dutiful, clinical, and moralistic: the very model of a modern Mormon legal. His Joe with Harper is brittle, evasive, almost frightened – not of her – of the domestic world she represents and his secrets she might intuit. His Joe on the phone with his mother feels like a regression to “Little Joey,” the obedient boy who knew the catechism of his conservative upbringing but didn’t yet have the vocabulary for sin, desire, or shame. And then there’s Joe with Louis, the affair that forces all the other compartments to bleed into one another. De Cicco doesn’t flatten these versions of Joe into a single, consistent reading. He stacks each version of his character, letting his own sense of self contradict when the material asks it. The result is a portrayal that locates Joe as the play’s experiment in identity loss: Can Little Joey coexist with Joe the homosexual? Can Joe the married man ever reconcile with the Joe who wants out of it? The answer may live in Part Two, but here in Part One, De Cicco gives us a character who’s still desperately trying to decide who he is depending on who’s in the room.

Because of the complexities of Joe Pitt, his wife Harper is, by design, a woman whose identity can’t quite stand on its own. In Part One, she exists first as Joe’s wife: one not yet as a fully-articulated character which makes her scenes feel inherently borrowed from his narrative. Portrayer Lauren Elizabeth Reed leans into that limitation and then subverts it during Harper’s Valium benders, which become the only moments where Harper gets to explore who she might be outside the marriage. On pills, she isn’t merely erratic; she’s curious, animated, occasionally funny, and almost free. Reed finds levity in those scenes, not because the material is light, but because Harper’s altered state grants permission to imagine herself beyond the veneer of Mormon domesticity. If we don’t yet “know” Harper in Millennium Approaches, we at least glimpse someone trying to learn herself in real time. Fortunately, neither Reed nor the production will rush that process. Part Two will likely give us a clearer picture, but in Part One, Reed makes the mystery feel intentional rather than underwritten.

Thomas Muniz tackles Roy Cohn with the exact flavor of New York gruffness one expects from a man who threatened to sue the universe into submission. His Roy is equal parts Gordon Gekko and Howard Beale – the Wall Street shark with a terrible bedside manner; a man who is eternally mad-as-hell and refuses to take “No” for an answer. Muniz plays him as someone who has only ever known forward motion and force of will, which makes the scenes in which he is told he will die particularly potent; Roy Cohn will not say “Yes” to death any more than he said “Yes” to failure or vulnerability. In contrast, Belize breezes through Millennium Approaches with an entirely different kind of power. Zoa Starlight Glows portrays Belize with an effortless buoyancy – this is a character who is neither victimized nor ornamental, but thriving. It may be Kushner’s slyest triumph within the play: the sole minority character is not written as suffering, nor embittered, nor tragic, but alive and certain. Belize does not exist to prop up the emotional needs of the other characters; they move through scenes with agency, wit, and a kind of knowing that suggests they understand survival better than anyone onstage. Glows makes Belize the most alive person in the room not by straining for it, but by letting the character’s certainty radiate. They know they will be okay, and that knowledge becomes its own form of resistance.

Janine Papin anchors the orbiting roles as Hannah Pitt while also slipping into a rabbi’s beard, a doctor’s coat, and Ethel Rosenberg’s stiff ghostly presence, each distinct enough that we willingly suspend the obvious fact that it’s the same performer simply changing hats, both literally and figuratively. Ame Livingston fills out the other corners of the play’s world as a nurse, a homeless woman, and a nun before finally revealing herself as the Angel, a casting choice that feels thematically deliberate: even before she sprouts wings, Livingston is already playing characters who tend, observe, and channel the divine. Paired with the physical presence of the other Angels (Brenna Arden and Ayanna Lúa), and supported by the principals who likewise slip into minor roles, the production populates its stage with a New York that feels bustling and fully inhabited despite the minimal scenic design. It’s a testament to the versatility of this ten-person company that no character feels like a placeholder. Even when the audience recognizes the face under the wig or the voice behind the accent, the strong performance does the imaginative work for us. In a play that blurs the boundaries between the real and the fantastical, the ensemble’s shape-shifting becomes part of the magic.

While much of the dramatic weight of Angels in America undeniably stems from the specter of AIDS, it would do the play – and Theater West End’s production – a huge disservice to reduce it to a story about disease alone. What the Theater West End cast and crew make clear is that Kushner’s work is as much about identity, loss, and the human struggle to reconcile who we are deep down with who we present to the world. Each performer, from Joe navigating his fractured sense of self to Prior and Louis negotiating intimacy and mortality, embodies that collision of private desire and public expectation. The multiplicity of roles played by the ensemble underscores this as well: actors are not just inhabiting characters, but reflecting the broader spectrum of what it means to be alive in America, to claim a life against impossible odds, and to endure in a world that can feel both absurd and cruel. The mythology Kushner evokes here – his angels, ghosts, and reality-bending visitations – exists not apart from humanity, but as a celebration of it. And it calls to mind, for me at least, a quote by writer Irna Phillips – the mother of the modern soap opera. Phillips penned this in 1957 as a response to viewers outraged that she had killed off the beloved Jim Lowell on “As the World Turns”:

“As the world turns, we know the bleakness of winter, the promise of spring, the fullness of summer, and the harvest of autumn – the cycle of life is complete. What is true of the world, nature, is also true of man. He, too, has his cycle.”

It is unlikely that Tony Kushner had the venerable daytime serial in mind when writing Angels in America, and I’m fairly certain Theater West End didn’t choose a rotating thrust stage to intentionally echo Phillips’ literal notion of the world turning — but as Millennium Approaches drew to its cliffhanger ending, I found myself thinking of that quotation. Partly because Part One ends on the kind of theatrical gasp only a soap can truly appreciate, but also because Kushner shares Phillips’ dramaturgical instinct: if we know the people, we will follow the story. By the time Prior sees the Angel, we have come to know these characters with the same intimacy one reserves for longstanding soap protagonists – not as caricatures or archetypes, but as human beings whose rhythms, micro-expressions, and contradictions feel stolen from real apartments, real hospital rooms, real park benches, or overheard through the Open Window of a New York tenement.

Angels in America remains one of the most important plays of the twentieth century not merely because of its intellectual or political heft, but because its realism is so emotionally precise that we recognize the people inside it. And it is that quality – that deeply human realness – that also animates the best of the soap tradition, where characters are known over time and change is earned. Theater West End’s production honors that tradition, whether it meant to or not, crafting a Part One so resonant, so well-lived-in, that the audience cannot help but crave its conclusion.

Tune in tomorrow, indeed.

ANGELS IN AMERICA, PART ONE: MILLENNIUM APPROACHES plays at Theater West End January 16 through February 1, with PART TWO: PERESTROIKA playing February 20 through March 8. Tickets can be acquired online or at the box office, pending availability. Photography by Damion Cornett Sr. (Production) and Bryan Jager (Behind the Scenes), used with permission.

Reader Reviews

Videos