Review: 'JOSEPHINE' & 'PAGLIACCI' at Union Avenue Opera

runs through August 2

Josephine — music and libretto by Tom Cipullo, 2016

Josephine Baker was a monumental presence in the last century. She rose from a St. Louis childhood of profound poverty to brilliant international celebrity. She’d been a street child sleeping in cardboard boxes. At eight she worked as a live-in domestic for a white family. At eleven she watched East St. Louis burn in the race riot. She was married at thirteen, divorced and married again at fifteen. She was a waitress, a street performer, a vaudevillian. She was, above all, a survivor.

She visited France with a touring show—and eventually became the toast of Paris. Singing and dancing—often in the near-nude—she demanded and received attention. She epitomized the free-spirited ‘20’s. She became a French citizen. She became the friend of royalty and genius. Picasso painted her. Hemingway met her at a night club and spent all night drinking champagne with her at her kitchen table, discussing love and their souls.

She had multiple lovers and husbands. She adopted twelve kids and fostered a thirteenth. She had a pet cheetah named Chiquita.

During the war she served daringly as an intelligence agent for the French Resistance—for which she was awarded great honors. She is a major French heroine with a place in their Pantheon.

Throughout her long career she was a clarion voice for civil rights.

Tom Cipullo’s short opera Josephine is set in 1975. It is a “monodrama” (i.e. the work rests entirely on the lovely shoulders of its soprano). It takes us into Josephine’s dressing room just before her final performance—a revue celebrating her fifty years in French show business. (The revue was financed by Prince Rainier, Princess Grace and Jackie Kennedy Onassis.)

It’s four days before her death.

She’s being interviewed.

Manna K. Jones gives us a complex Josephine. Strong-willed, demanding, yet vulnerable. This Josephine is justifiably a diva. (The orchestra is waiting, waiting to begin rehearsal, but Josephine repeatedly cries out “Not now!”) Ms. Jones has a rich velvety voice capable of deep drama. And that velvet endures as she lofts into her very highest notes—which seem dreamily easy and almost endless. A number of times a high note is shot, like a bright spear, straight up into the dome of this church-cum-opera-house. Acoustically this works beautifully.

Tom Cipullo’s score calls for only a small ensemble: violin, cello, flute, clarinet, and piano. The music is rich and melodic. Occasional wisps of jazz suggest the era of Josephine’s rise to stardom. The score is haunted by a phrase or two from Josephine’s signature song, “J’ai deux amours”.

This is a lovely work, beautifully performed. But it seems more a “monologue” than a “monodrama”. It remains (dramatically speaking) an interview, with little more structure than one expects from that genre. A one-person dramatic opera is surely possible. Look at Poulenc’s La voix humaine, which Opera Theatre of St. Louis gave us four years ago. In it a solitary woman desperately clings to a doomed romance. It has that central requirement of drama: human conflict and resolution. The lost lover is present only inaudibly at the far end of a phone conversation—but he’s essential to the drama. The conflict is resolved unhappily, but it is resolved.

The opera Josephine shows us a startlingly talented, many-faceted entertainer. We see her fiercely engaged in the struggles against racism and Nazism—but these are social forces outside the confines of the stage. The only human conflict we see on stage is that between the orchestra and the diva who refuses to start the rehearsal. This is too petty to support “drama”.

So, it’s not a drama we see. But it is a tightly compact, fascinating mini-biography of an amazing woman. Running time is about thirty minutes.

Now to the second half of the double-bill.

Pagliacci — Music and libretto by Ruggero Leoncavallo, 1892

Now this is a drama! In fact, like so many operas of its era, it is a melodrama. Pagliacci has retained great popularity ever since it’s opening. It has the classic conflict— the love triangle (or in this case it’s a “love square”).

We have a prologue, a play, and a play-within-a-play. The run-time is about seventy minutes.

It’s “Carnevale!” (i.e. Mardi Gras) A Commedia troupe arrives in a small Sicilian town. It’s led by Canio who plays Pagliacco the clown. The players include Nedda (Canio’s beautiful wife), Tonio (who lusts after Nedda), and Beppe. Nedda is ready to flee this vagabond life. Her affections are swiftly won by Silvio, a handsome local swain. So—three guys, one woman. Conflict!

The show begins with a simply glorious Prologue. This, in the manner of Shakespeare, introduces the audience to the story they’re about to see. And it stresses the players’ dedication to Reality (as opposed to the artificiality presented in most theater of that time.) This is verismo opera. Real people! Real passions! Not the corporate “passions” bandied about today which so cheapen the word. (“Diabetes is our passion!” Now really!) In Pagliacci we see real old-fashioned passions based on love and honor. Passions with high stakes. Passions for which one would readily die. And Leoncavello’s music beautifully supports those passions. It makes us totally believe in them.

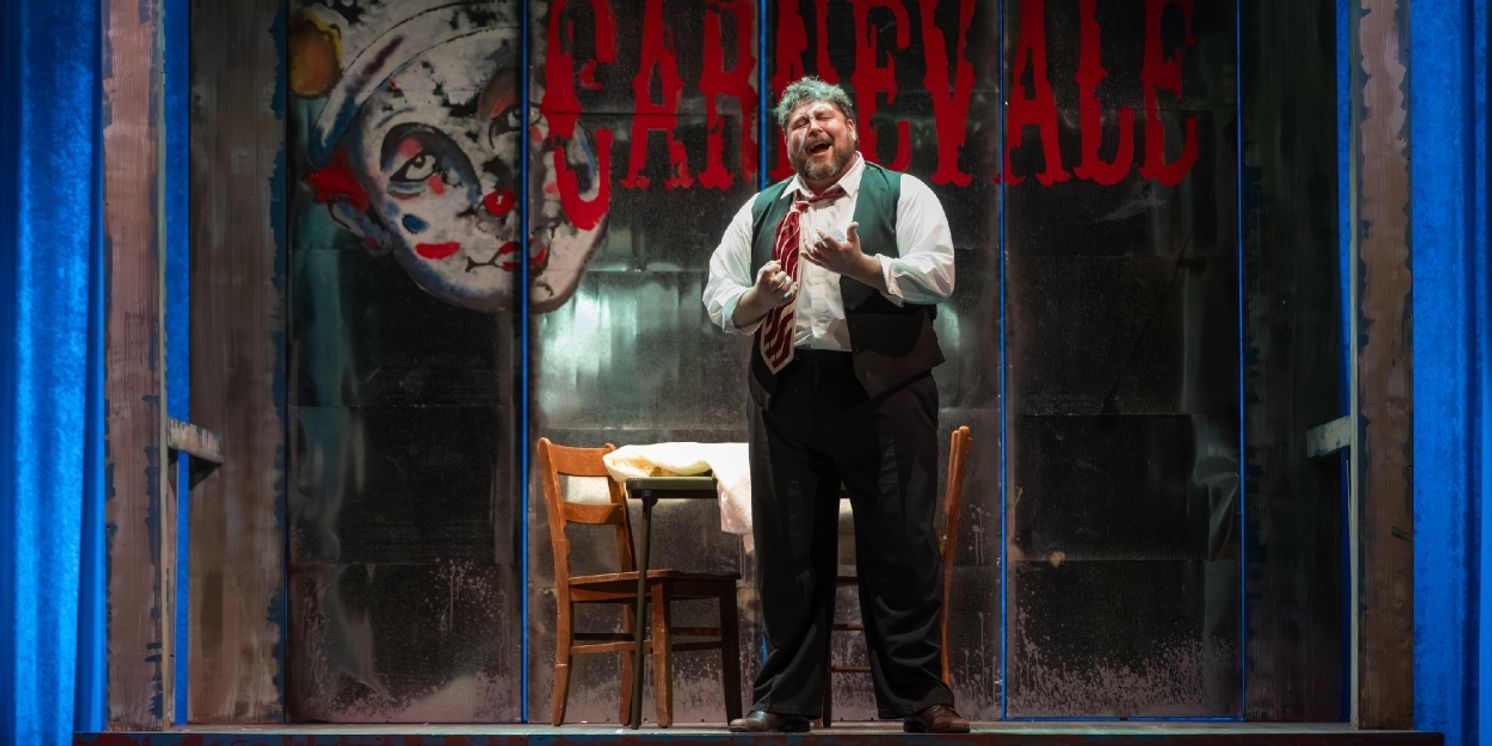

Andy Papas triumphs in the prologue. In St. Louis we’ve seen his great comic gifts in Yeomen of the Guard, The Mikado, Barber of Seville, and Don Pasquale. In Pagliacci he gets to blend comedy and villainy. From the first note of the prologue I was awed by the sheer power and drama of his voice.

Meroë Khalia Adeeb is also becoming familiar to St. Louis audiences. Last year at OTSL she sang two widely contrasting roles in their New Works Collective, then gave lovely new dimension to Micaëla in Carmen. Now she sings Nedda—and she’s stunning. Her bird aria, “Ballatella”, is enchanting, blending her sweet soprano with the orchestra’s impersonation of a flock of birds “thirsty for the blue sky”. Nedda yearns to be so free.

The title role, Pagliacco (Canio), is sung by Jonny Kaufman. Canio is convinced his wife is unfaithful to him. But the show must go on. Mr. Kaufman does quite glorious justice to one of the greatest, most popular, most passionate arias in all of opera—“Vesti la giubba!” (“Put on the costume!”) “Put on the costume, Clown. Laugh though your heart is breaking. Laugh through your tears! Laugh, Clown, laugh! It’s your job!” Mr. Kaufman sings with such power and passion and commitment, and he’s supported by Leoncavallo’s irresistably passionate music. If this doesn’t compel you to embrace a Victorian frame of emotions then nothing will.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

and Kenneth Stavert

Silvio, Nedda’s lover, is sung by Kenneth Stavert. He does beautiful work. His love duet with Nedda, where he pleads with her to have the courage to run away with him is so romantic, so seductive. It’s sexy as hell, and it shows both beautiful voices at their very best.

Marc Schapman has been very busy on our opera stages for the last decade or so. Among other roles he has sung Mime in Siegfried, Tateh in Ragtime, and Monostatos in Magic Flute. Here he does fine work as Beppe (Arlecchino). His comedy is deft and precise.

There is a lovely shift of style when the Commedia actors start the play-within-the-play. We see Columbina (Nedda) awaiting the arrival of her husband Pagliacco (Canio). The comic servant Taddeo (Tonio) awkwardly woos her, then Arlecchino (Beppe) comes to serenade her. This is all done in a delightful cartoonish style, the way the old Commedians might well have done. And of course the scenario echos what’s happening in real life outside the theater.

Then Pagliacco arrives and here the line between acting and real life gets very tenuous. It becomes a little Pirandello. Canio is drunk with jealous rage and can barely keep to the scenario. Finally he abandons it and demands that Nedda tell him the name of her lover. I’m reluctant to give you a “spoiler”; I’ll just say the rest is violence and blood.

And in the end Tonio gives one of opera’s most famous final lines, which book-ends nicely with his Prologue. With leaden gravitas and finality he proclaims, “La commedia è finita!”

There is a large and excellent chorus which sings beautifully throughout. Over the past several years Union Avenue’s chorus seems to be getting better and better. Their graceful entry and exit down the aisles gives the audience an intimacy and acoustical variety which is quite lovely.

The decision to place the show in 1949 Sicily works well. Since 1946 Sicily has been an “autonomous region” of Italy—a status in which it may comfortably retain the ancient traditions which make it a distinctive culture. The passionate sense of honor we find in Pagliacci seems at home here, as do the travelling players.

-------

Kathryn Frady directs both Josephine and Pagliacci. She gives a natural visual variety to the former, and in the latter she handles the chorus beautifully, making them a group of realistic individuals. The clever heightened-reality style in the play-within-the-play is charming indeed. And the violence is convincingly staged.

Conductor Stephen Hargreaves masterfully leads both the quintet in Josephine and the twenty-piece orchestra in Pagliacci. For Pagliacci he draws every single ounce of emotion out of that score. Marvelous!

Design work is excellent throughout. Laura Skroska did the sets. For Josephine we see a simple, comfortable dressing room. For Pagliacci there is a rustic temporary stage backed with narrow rotating panels—hinting at the old periaktoi used by the Greeks. In one position the panels display an enormous poster for the traveling company. It shows a great face of Pagliacco and (hugely written in blood red) the word “CARNEVALE”. This poster is a masterpiece. It’s old. It’s been ill-used. Its paint is flaking. And it almost drips theatrical anguish and threat.

Costumer Teresa Doggett gives her amazing best. Josephine glitters properly in a blue evening gown. The villagers and players in Pagliacci are clothed as fits the time and place—with nice variety within an overall sense of unity of palette and style.

Patrick Huber designed the lighting. The two shows have quite different lighting demands, yet Huber deftly serves both masters.

The Union Avenue Opera Theatre presents Josephine and Pagliacci through August 2.

For tickets visit unionavenueopera.org/

(Photos by Dan Donovan)

Reader Reviews

Videos