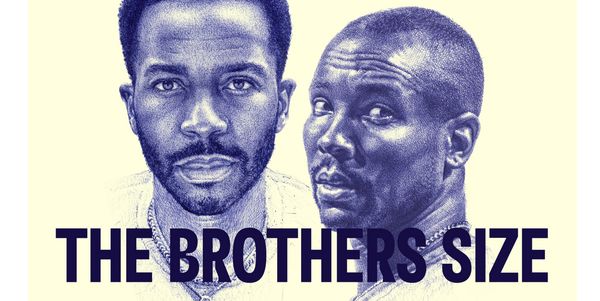

Review Roundup: THE BROTHERS SIZE Opens Off-Broadway at The Shed

The show is now playing at The Shed in a production co-directed by Bijan Sheibani and McCraney and starring André Holland, Alani iLongwe and Malcolm Mays.

Tarrell Alvin McCraney’s The Brothers Size is now playing at The Shed in a production co-directed by Bijan Sheibani and McCraney and starring André Holland, Alani iLongwe and Malcolm Mays. This new production of The Brothers Size, co-produced by The Shed and the Geffen Playhouse comes on the 20th anniversary of McCraney’s groundbreaking drama.

From Tarell Alvin McCraney, the Academy Award–winning storyteller behind Moonlight, comes a modern-day fable about life after incarceration and the struggles of family, duty, and freedom. This intimate, lyrical new production is presented in the round with live music, incorporating the rich storytelling tradition of the Yoruba people of West Africa.

Read the reviews here!

Matt Windman, amNY: For all its beauty and occasional flashes of humor, “The Brothers Size” remains more evocative than fully satisfying. At 90 minutes, it drags in places, its lyrical style and deliberate pacing sometimes testing patience. It works best as part of the larger “Brother/Sister” cycle, where its themes of loyalty, family, and survival resonate more deeply.

Matt Windman, amNY: For all its beauty and occasional flashes of humor, “The Brothers Size” remains more evocative than fully satisfying. At 90 minutes, it drags in places, its lyrical style and deliberate pacing sometimes testing patience. It works best as part of the larger “Brother/Sister” cycle, where its themes of loyalty, family, and survival resonate more deeply.

Thom Geier, Culture Sauce: What’s unusual about The Brothers Size, and what has enabled it to endure in multiple productions since its premiere, is that it combines the flashy showmanship of a young artist with an unexpectedly polished maturity. There’s a simple elegance to the storytelling, enhanced by shifts into poetic language heightened by Spencer Doughtie’s lighting cues. It’s a work of ambition but also of modesty, willing to explore masculine vulnerability as well as braggadocio. Perhaps that’s the truest reflection of the experience of Black men, whose very bodies have been placed in jeopardy (and behind bars) with such frequency. In the face of such systemic brutality, why not try a little tenderness?

Thom Geier, Culture Sauce: What’s unusual about The Brothers Size, and what has enabled it to endure in multiple productions since its premiere, is that it combines the flashy showmanship of a young artist with an unexpectedly polished maturity. There’s a simple elegance to the storytelling, enhanced by shifts into poetic language heightened by Spencer Doughtie’s lighting cues. It’s a work of ambition but also of modesty, willing to explore masculine vulnerability as well as braggadocio. Perhaps that’s the truest reflection of the experience of Black men, whose very bodies have been placed in jeopardy (and behind bars) with such frequency. In the face of such systemic brutality, why not try a little tenderness?

Melissa Rose Bernardo, New York Stage Review: Chronologically, The Brothers Size is the second play in the trilogy, but McCraney wrote it first. That probably explains why the 90-minute-play stands on its own so well. But don’t be surprised if, at the end, you find yourself wanting to know more about these men. Fortunately, you can pick up The Brother/Sister Plays and read Elegba’s, Ogun’s, and Oshoosi’s stories from the beginning.

Melissa Rose Bernardo, New York Stage Review: Chronologically, The Brothers Size is the second play in the trilogy, but McCraney wrote it first. That probably explains why the 90-minute-play stands on its own so well. But don’t be surprised if, at the end, you find yourself wanting to know more about these men. Fortunately, you can pick up The Brother/Sister Plays and read Elegba’s, Ogun’s, and Oshoosi’s stories from the beginning.

David Finkle, New York Stage Review: That alone is worth the price of admission. Okay, the entire production is worth more than the price of admission. If there’s any drawback to what’s on view, it may be that the early clowning somewhat delays McCraney’s up-close-and-personal view of brothers unsuccessfully trying to align. (Inevitably, men in the audience who have a brother will focus, even if fleetingly, on their sibling.)

David Finkle, New York Stage Review: That alone is worth the price of admission. Okay, the entire production is worth more than the price of admission. If there’s any drawback to what’s on view, it may be that the early clowning somewhat delays McCraney’s up-close-and-personal view of brothers unsuccessfully trying to align. (Inevitably, men in the audience who have a brother will focus, even if fleetingly, on their sibling.)

Elysa Gardner, The Sun: The exchanges that follow segue from effusive, bittersweet humor to shattering sadness, with Messrs. Holland and iLongwe — the latter is equally potent and can be especially funny, when he’s not breaking your heart — evince the mix of responsibility, guilt, and, above all, love that makes Ogun’s relationship to his brother so tender and tragic.

Elysa Gardner, The Sun: The exchanges that follow segue from effusive, bittersweet humor to shattering sadness, with Messrs. Holland and iLongwe — the latter is equally potent and can be especially funny, when he’s not breaking your heart — evince the mix of responsibility, guilt, and, above all, love that makes Ogun’s relationship to his brother so tender and tragic.

Jonathan Mandell, New York Theater: “The Brothers Size” is a kind of dance, in some ways literally (the performers moving around that white circle to the sound of the drums) but also metaphorically – a swirl of envy and resentment and deep love that engages all three characters in different, fascinating and (of course) oblique ways.

Jonathan Mandell, New York Theater: “The Brothers Size” is a kind of dance, in some ways literally (the performers moving around that white circle to the sound of the drums) but also metaphorically – a swirl of envy and resentment and deep love that engages all three characters in different, fascinating and (of course) oblique ways.

Kyle Turner, New York Theatre Guide: Holland, having emanated something similar all those years ago in the same role, thus gives his Ogun the tragedy of understanding, making him feel all the more devastated by Oshoosi’s surrender to something that may prove self-destructive. But perhaps it’s that same awareness, and touch of history within the production itself, that allows the finale to land with such revelatory beauty, fueled by an incendiary hope and fraternal bond.

Kyle Turner, New York Theatre Guide: Holland, having emanated something similar all those years ago in the same role, thus gives his Ogun the tragedy of understanding, making him feel all the more devastated by Oshoosi’s surrender to something that may prove self-destructive. But perhaps it’s that same awareness, and touch of history within the production itself, that allows the finale to land with such revelatory beauty, fueled by an incendiary hope and fraternal bond.

Billy McEntee, 1 Minute Critic : As in the Oscar-winning Moonlight, McCraney unravels the nuances, vulnerabilities, and shimmering love that shape Black masculinity. In this stellar revival, the performances and production match the writer’s clarity.

Billy McEntee, 1 Minute Critic : As in the Oscar-winning Moonlight, McCraney unravels the nuances, vulnerabilities, and shimmering love that shape Black masculinity. In this stellar revival, the performances and production match the writer’s clarity.

Helen Shaw, The New Yorker: Twenty years have done something wonderful to McCraney’s play. It now feels more like an assured masterpiece than the first work of a prodigy; here, polished to a deep lustre, is the finest exertion of McCraney’s talents, elevated by a cast with staggering gifts. Holland’s self-effacing tiredness as Ogun is deliberately unshowy, and, while the actor’s name appears above the title in the program, he cedes the limelight to both Mays, who gives the graceful, flirtatious performance of a lifetime, and to iLongwe, who grows more radiant and funny as Oshoosi’s frustration with his brother sharpens. A certain inelegant hastiness in the plot has been resolved by treating the monologues almost as arias, giving them each an equal sense of grandeur, like the relentless finale of a fireworks display.

Helen Shaw, The New Yorker: Twenty years have done something wonderful to McCraney’s play. It now feels more like an assured masterpiece than the first work of a prodigy; here, polished to a deep lustre, is the finest exertion of McCraney’s talents, elevated by a cast with staggering gifts. Holland’s self-effacing tiredness as Ogun is deliberately unshowy, and, while the actor’s name appears above the title in the program, he cedes the limelight to both Mays, who gives the graceful, flirtatious performance of a lifetime, and to iLongwe, who grows more radiant and funny as Oshoosi’s frustration with his brother sharpens. A certain inelegant hastiness in the plot has been resolved by treating the monologues almost as arias, giving them each an equal sense of grandeur, like the relentless finale of a fireworks display.

Maya Phillips, The New York Times: For as much as the play is about the very real and very prescient themes of Black incarceration, brotherhood and Black masculinity, “The Brothers Size” doesn’t feel as grounded as it needs to be to make these relationships and motifs sing. The show has the capacity to explore this deep lyricism while maintaining its footing, however, as it proves in a quiet scene late in the play where Oshoosi and Elegba are sitting outside at night. Here the show slows its pace to linger with these men; the lights dim and the sound of crickets chirp in the background. It’s the scene that stays so vividly in my mind not for any particular line delivery or turn in the plot but because it is where the abstract most gracefully meets the concrete. That was where the play felt most alive.

Maya Phillips, The New York Times: For as much as the play is about the very real and very prescient themes of Black incarceration, brotherhood and Black masculinity, “The Brothers Size” doesn’t feel as grounded as it needs to be to make these relationships and motifs sing. The show has the capacity to explore this deep lyricism while maintaining its footing, however, as it proves in a quiet scene late in the play where Oshoosi and Elegba are sitting outside at night. Here the show slows its pace to linger with these men; the lights dim and the sound of crickets chirp in the background. It’s the scene that stays so vividly in my mind not for any particular line delivery or turn in the plot but because it is where the abstract most gracefully meets the concrete. That was where the play felt most alive.

Average Rating: 81.0%

- To read more reviews, click here!

- Discuss the show on the BroadwayWorld Forum