Exclusive: How Jerry Mitchell & Co. Made Technicolor Magic In BOOP! THE MUSICAL with 'Where Is Betty?'

BOOP! THE MUSICAL is playing now at Broadway's Broadhurst Theatre.

This season, technology is making a splash on Broadway. From the steadicam ops at Sunset Blvd. and The Picture of Dorian Gray to the state-of-the-art spectacle that is Stranger Things: the First Shadow the conventions of modern cinema are making their mark on midtown. While innovation has plenty to offer, however, old school theatre fans know that true Broadway magic begins and ends with good, old-fashioned imagination.

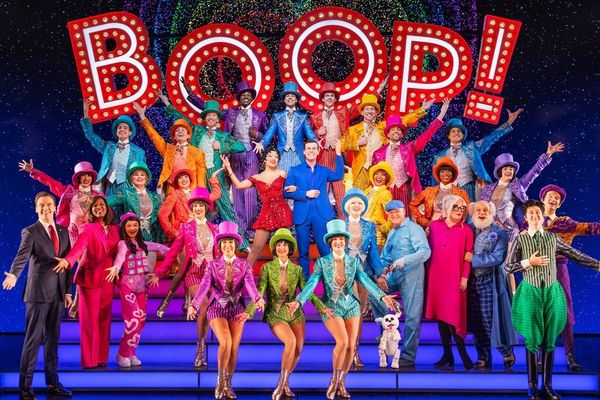

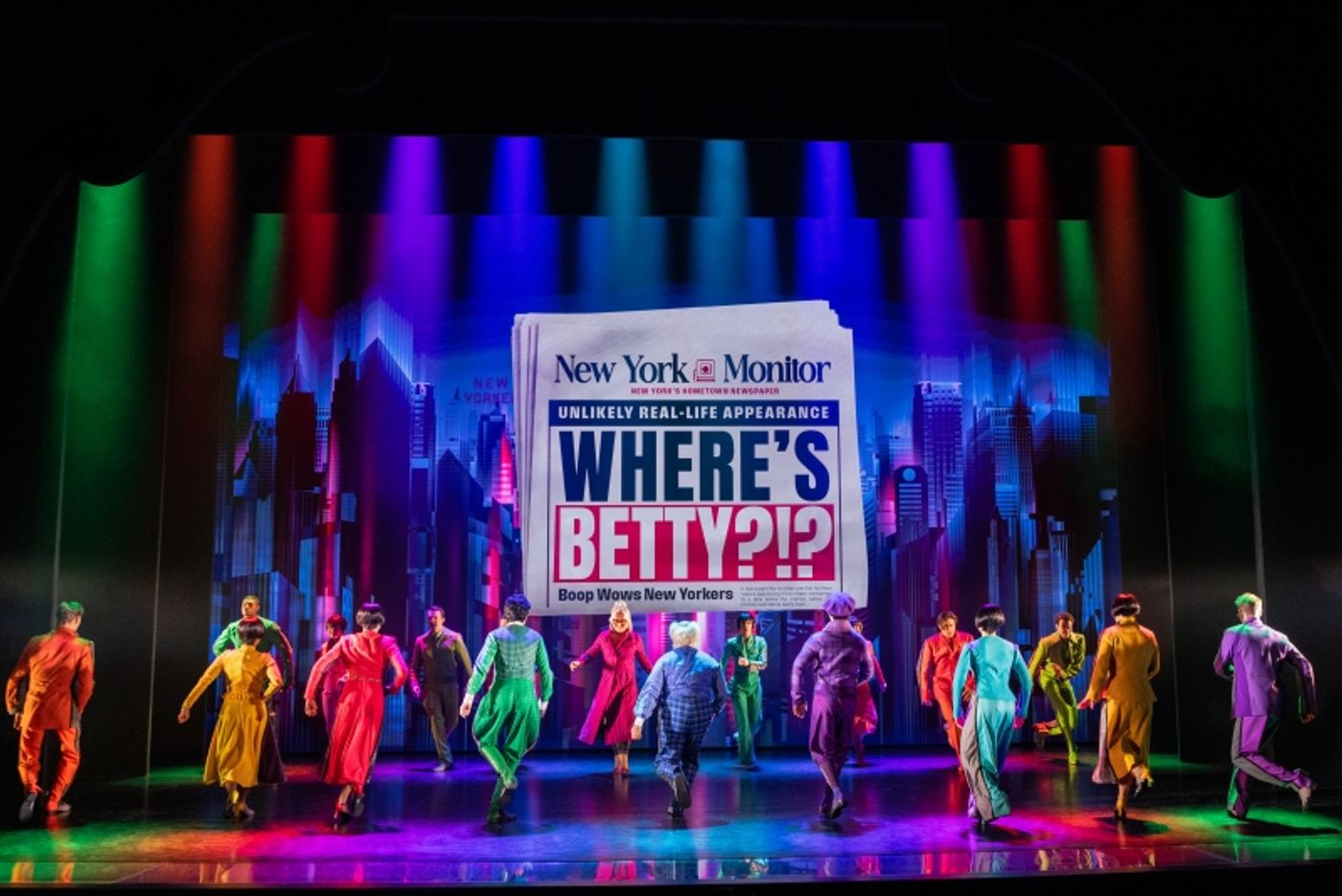

Few theatrical moments in recent memory have displayed as much imagination or generated as much buzz as BOOP! The Musical’s standout number “Where Is Betty?” a dazzling visual spectacle that toggles between black-and-white and full-color worlds, blurring the line between animation and reality. With its clever design, kaleidoscopic costuming, and choreographic sleight-of-hand, the number has proven captivating for both audiences and social media feeds alike.

To understand how the team achieved their fully-practical magic, we sat down with director-choreographer Jerry Mitchell, whose Broadway credits include everything from Kinky Boots to Legally Blonde. In this conversation, Mitchell unpacks the inspirations behind “Where Is Betty?”, the challenges of post-tryout rewrites, and how a cartoon icon like Betty Boop inspired a celebration of theatricality in its purest form.

Broadway is going in a very technological direction, which is creating such exciting new potential for stories told onstage, but what you’ve done with “Where Is Betty?” is such a gorgeous example of old-school theatrical sleight of hand. How did it come to be part of the show?

Jerry: Well, first of all, you know I love a showstopper, right? Especially at the beginning and the end of an act. What happened was we were in Chicago, and we were doing that fabulous number in black and white—the opening number, which is another showstopper in its own right. And I was watching the audience reaction to that number, right? So we didn’t have the “Where Is Betty?” number. It was sort of a reprise of all the kids on their cell phones texting and calling each other like, “Where’s Betty? You won’t believe it. Better sit down. Betty and Steve—look who’s in town.” It was all talking about Betty Boop being discovered in town and she’s real. And it just felt like the audience was expecting a showstopper.

One of the things I love about going to Chicago is, if you're smart and you pay attention, you learn from what you've created and how the audience is responding to it. And they'll tell you where they want more and where they want less. And so this was one place that they definitely wanted more. They wanted to start the second act the way we had started the first act, with that feeling of confidence and a production number that really sets the tone for the whole rest of the show and the rest of the act.

Were there any musicals or classic films you used for reference?

I had skirted the idea of the two worlds existing at the same time with some sort of a costume that would make that doable. And, you know—of course I was thinking of all the numbers that I’ve either performed in or loved myself. Like 'Favorite Son' from The Will Rogers Follies. I was thinking about Grand Hotel, that beautiful, simple number—“We'll Take a Glass Together”—and everybody’s just doing a Charleston step. So simple. And then I thought about my own—“Don’t Break the Rules” from Catch Me If You Can and “So Much Better” from Legally Blonde. Simple, simple, simple ideas.

There are a few elements working together to create the misdirection of the number and a major piece of that is the costume design. Can you elaborate on the design of the double-sided costumes?

So I got an idea for this costume thing, and I called Gregg Barnes. And I said, “Gregg, I have an idea. We’ve all seen the person do the routine where they’re the bride and the groom, and it’s split down the middle. One side of them is dressed as the bride and one side is dressed as the groom. If you're facing them, it’s right down the middle, like down the nose.”

I said, “What if we put the slit on the side? So the front side of a person is the black-and-white cartoon world, and the backside of the person is the world of color—or vice versa.” So I could line all of our cast up in a row, and when half of them are facing downstage and half are facing upstage, you get a full line of color or a full line of black and white. And I just keep switching it and play on that theme. And he said, “I think that could work.” And I said, “Why don’t you mock it up for me in sweatpants? Get four sets of colorful sweatpants and four sets of black or gray sweatpants. Cut 'em in half and then stitch 'em back together—two sets with black on the front and two sets with color on the front, vice versa. And give 'em to me, and I'll get some dancers in the room, and I'll start playing with this idea.

Once I knew I wanted to do it, I picked the cast. They're not all boy, girl, boy, girl in those lines — it's all mixed up. I picked it by size. Then I had to give that to Gregg because once he made the costume, I couldn't switch anybody around. They had to be with their pair. We laid out a color chart of what would be on the color side, and basically a hue for each color. Like, if it's green, there might be three greens; if it's pink, there might be three pinks; or if it's blue, there might be three or four blues — and some texture in there too. That's what's so beautiful. If you look at those costumes in detail, they're stunning. Gregg didn’t just throw color — he threw real shapes and silhouettes on each of those people. It's just magnificent.

How long did it take to get the bones of the number on its feet?

We went into the studio, and in March, I choreographed the whole number and also sort of sketched out musically what I wanted the number to do with Zane Mark, my dance arranger. It was lots of planning — over a year of planning. Finally, when I saw the costumes and the sweatpants together, I knew it was going to work. Then we had to go to the producers and say we need a set of costumes because they're not used anywhere else in the show. And we just went for it. As soon as we got it on stage — the cast had been rehearsing with me at the rehearsal studio, obviously, this new number — we only had two and a half weeks before we went into tech rehearsal.

Once we got the costumes on stage, I had to spend two days just trying to light it properly with Philip [Rosenberg] to make sure I saw as little of the other side — particularly in the beginning — as possible, so you would get the effect of the switch. That was the thing I learned in Chicago with the clothes and the projections. I think numbers like this are spectacular when they start in a very simplistic place and then go a little crazy. That’s what I was trying to do with it — starting as simple as I could and then getting as crazy as I could, of course, with the full company. I've got incredible dancers up there. And I have Steven and Faith and a couple of the others who are actors who move well. So I had to make sure everybody was capable of doing the steps. And I had to teach it kind of quickly because, like I said, we had two and a half weeks in the room before we were on stage doing tech.

The technical element of the number is so crucial. The lighting and projections truly make it come alive. What was the tech process like? How long did it take to inegrate all these elements so seamlessly?

One of the other things I did in the projections because the projection worlds have to change with us as quickly as we flip: I did this all throughout the process on this number, I would film, in a studio, my pre-production dancers doing the choreography, and then I would send that video of my dancers to [projection designer] Finn [Ross]. Finn would take the arrangement and the dancers, and put them in a little box on his computer. He would show me what the walls were going to be projecting while they were dancing. Then he'd make a video of that and send it back to me. So we communicated back and forth in real time. He was in the UK, and I was here a lot of the time, but we would communicate by watching what the walls were doing based on what my dancers were doing in the pre-production room.

That was an incredible process for me because we were able to accomplish so much of the technical work before we actually got into technical rehearsal. The minute we walked into the theater, I already knew what the video screens were going to be doing. It was just a matter of adjusting for size, of course, in the theater, but the information — I had already seen it, so it wasn’t surprising to me. We had collaborated on what the projections would do — how they would switch, whether they would flip, come from the bottom up, fade — all of those kinds of choices we made before we actually saw the number with the dancers. And it saved hours and hours of technical time.

If I had waited to do it the first day of tech, we would have spent two weeks just on that number. So I had to do the costumes ahead of time, I had to do the video projections ahead of time, I had to do the musical arrangements ahead of time. The first time we were all together in technical rehearsal, I actually already knew in my head that they all were going to work together. I just needed to be proved right by seeing it. You spend the time creating it and designing it with each team and each department, and then you put it together and cross your fingers. But I was pretty confident this was going to work.

The number also feels like a feat of stage management and more specifically, cue calling. The timing is never quite the same and it is on a hair trigger. The folks in the light booth and whomever is calling the cues must be superhuman.

That is my brilliant stage manager, Bonnie Becker, who was my PSM on Legally Blonde. She is absolutely, 100% responsible for the blackout when Elle Woods jumps in the air at the end of Act One. Bruiser, the dog, was supposed to run out to Laura Bell [Bundy], and she's supposed to hold him up in the air — blackout. We were in San Francisco-- the dog would not go. So Laura Bell just jumped in the air. At the last beat, Bonnie Becker called the blackout while she was in the air. And I went, that's it. We're not bringing the dog on. That is how we're ending the act.

Oh my gosh. And that's who is calling the cues! Bananas. Were there any challenges that surprised you in the staging of this number?

I think part of it was the planning and experience. Really, it's about experience. I think the hardest challenge in the number was, once we got it on stage, Philip and I had to light it. When we first did it the very first night — of course, everybody went crazy because it was this new number and this new idea — but the lighting wasn’t right. I could see too much of the other side of the costume.

When they first enter, they're doused in color — the color world is facing upstage on the downstage side, and the upstage side is facing downstage. It's all color. I said to our lighting designer, Philip Rosenberg, "Douse them in color, so I don't see any black and white." And then, when they turn around for that first time, all of that color light turns into white light — and the audience goes, "What just happened? What the hell just happened?" And then, when we turn back to color, they realize — "Wait a minute. My mind wasn't playing tricks on me. Oh my God, those costumes are two-sided!" So then they're in on the storytelling.

It's such a terrific magic trick, so uniquely theatrical, and the audience absolutely loves it. Is leaning into the unique strengths of theatre and preserving those traditions something you consciously consider?

For me, theater will always be about the live element — the live experience. That will never, ever go away. I worked with Michael Bennett for the last couple of years of his life. I was Michael's associate and a dancer in Scandal — one of the last musicals he worked on that never came to Broadway. It was during that period, during Scandal and while we were creating Chess, that Robin Wagner, Michael Bennett, Bob Avian, and myself were in a room together and I was listening to how they were using the influences of film to make theater seamless. The best example of that for Michael, obviously, was Dreamgirls. Dreamgirls was almost like a film in the sense that the transitions were seamless. From the curtain of the first act to the curtain of the second act, there are no blackouts — it just moves.

I'm always aiming for that idea. I'm aiming for making seamless transitions. I think transitions can make or break a musical. When I go see a musical and I have to stop and wait for the scenery to change — today, in today's world, with all the technical things available to us — unless it's a real choice by the director to stop, I'm always confused. Why would you do that? Why would you waste time on the transition when you can make the transition mean something? It's part of the storytelling.

How you do that — whether you do it with an actor, or you do it with a video, or something else — I'm less concerned about. As long as the experience is live, and living, breathing, and moving.

Get a peek at the showstopping, "Where Is Betty?" and a better look at Gregg Barnes two-toned costumes here!

Check out some of Jerry's inspo for the number here!