5 Incredible Discoveries from the Stephen Sondheim Collection at the Library of Congress

From lyric drafts to music manuscripts, the collection offers a historic and extensive look at the process of one of the greatest musical theatre writers of all time.

Do you have a burning Broadway question? Dying to know more about an obscure Broadway fact? Broadway historian and self-proclaimed theatre nerd Jennifer Ashley Tepper is here to help with Broadway Deep Dive. BroadwayWorld is accepting questions from theatre fans like you. If you're lucky, your question might be selected as the topic of her next column!

Submit your Broadway question here!

Earlier this year, it was announced that the Library of Congress had acquired the Stephen Sondheim collection. The legendary composer and lyricist passed away in 2021 at the age of 91 after a long and extraordinary career. His collection at the Library of Congress is in the midst of being catalogued, with the boxes that have been processed now available to the public for educational and scholarly purposes.

This month, I traveled to Washington D.C. and spent several days poring over Sondheim’s lyric drafts, music manuscripts, rewrite notes, brainstorm pages, song list outlines, and more. The collection offers a historic and extensive look at the process of one of the greatest musical theatre writers of all time. For theatre fans who love Sondheim’s work or writers interested in seeing renowned technique up close, there is no greater pleasure than spending time in the Sondheim collection.

In this first of a three-part series, check out five incredible discoveries I made in the Sondheim collection at the Library of Congress:

1. Some of Company’s most iconic moments were not in early drafts of the show.

One might assume that April the flight attendant was given her name just to set up “Barcelona”’s best joke: that Robert forgets the name of the woman he just slept with and guesses “June”, another month. But actually, early drafts of “Barcelona” show that Bobby used to blurt out the name “Barbara” before April corrected him.

It is staggering to see the amount of rewrites Sondheim gave every song until he was satisfied with every single syllable. Seeing the man who gave us “Another hundred people just got off of the train” consider “Another hundred people just got out of their cars” makes one deeply appreciate just how much writing really is rewriting.

The endless pages of free-form word association result in tools that make each song sharp and specific, so Sondheim never hesitated to throw unformed or first drafty ideas on the page and hone from there. We could never have the utter brilliance of “Or they find each other in the crowded streets/ And the guarded parks/ By the rusty fountains and the dusty trees/ With the battered barks/ And they walk together past the postered walls/ With the crude remarks” without notebook pages brainstorming phrases like “beercan lakes” and “candy-wrappers winter breeze”. The iconic ode to New York that has regularly stopped performances of Company and become a standard can be viewed in all of its messy, beautiful development.

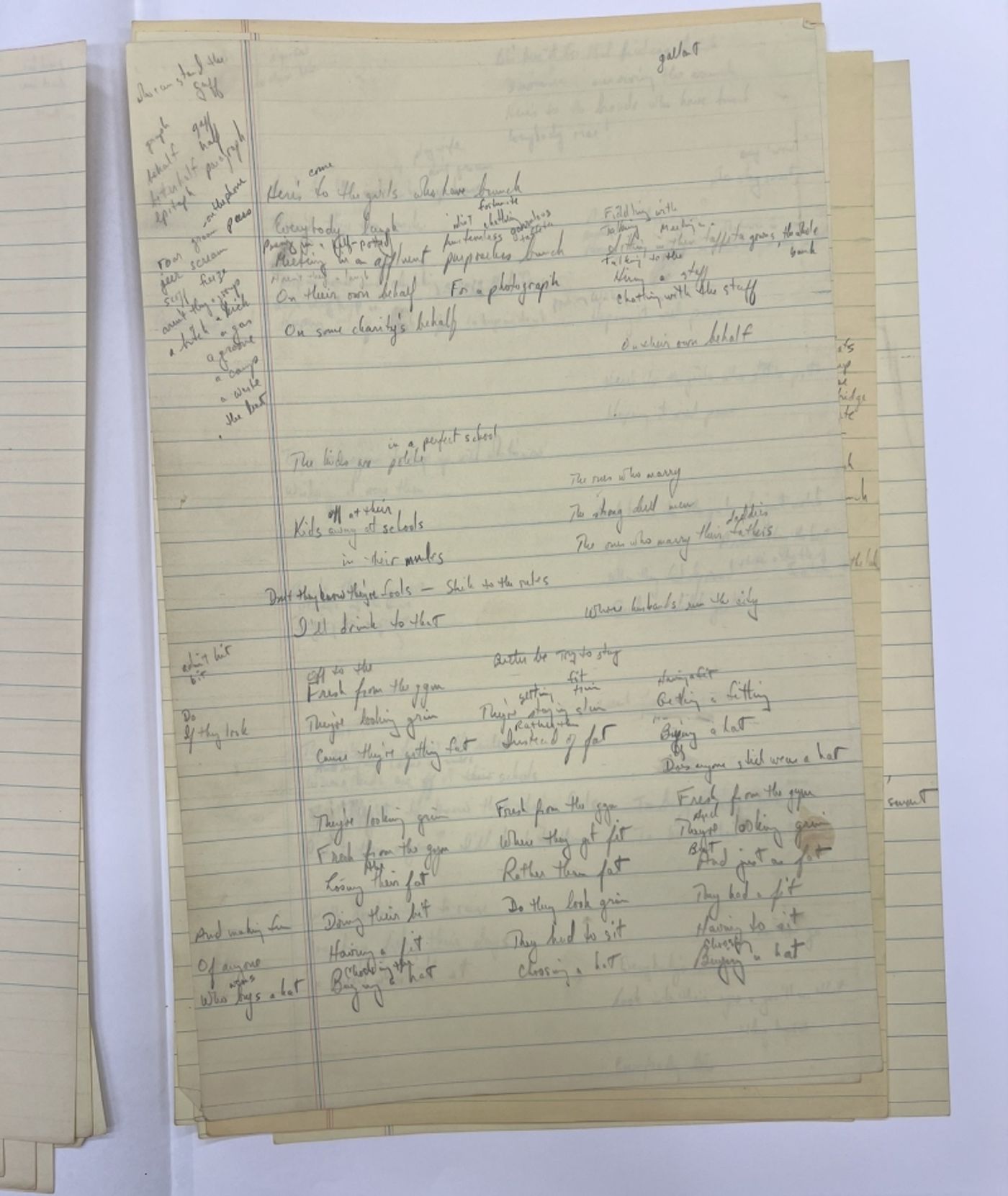

Obviously, no song arrives fully formed when it comes to lyrics, but seeing a draft of “Ladies Who Lunch” that begins with “Here’s to the girls who have brunch”, on a page covered in other lyric ideas, is fascinating. While archives may one day hold only the digital record of important writer’s rewrites, seeing the evolution of each Sondheim song as he created them in his own hand, showing one idea leading to another, is extraordinary.

2. Sondheim wrote quite a few unused or unfinished songs for the 1996 film The Birdcage.

All that remains of Sondheim’s original work in the beloved 1996 film The Birdcage is a snippet of his song “Little Dream”, sung by Nathan Lane’s character. The Mike Nichols-helmed blockbuster starring Lane and Robin Williams was based on La Cage Aux Folles—not the 1983 Broadway musical, but the 1978 movie of the same name, which was in turn based on a 1973 French play.

While only a small portion of “Little Dream” appears in the movie, the entire song can be heard on the movie’s soundtrack—and the song is also featured on the 1997 album, Sondheim at the Movies, as sung by Susan Egan. In his tome, Look, I Made a Hat, Sondheim notes that Nichols also had him write an opening number for the film, called “It Takes All Kinds”, which was cut. He wasn’t too miffed by the situation, sharing that the ins-and-outs of working on films didn’t distress him the way a similar situation in the theatre might have. Several of Sondheim’s previously written songs, such as “Love is in Air”, cut from Forum, and “Can That Boy Foxtrot”, cut from Follies, are in the movie in lieu of the original songs he penned.

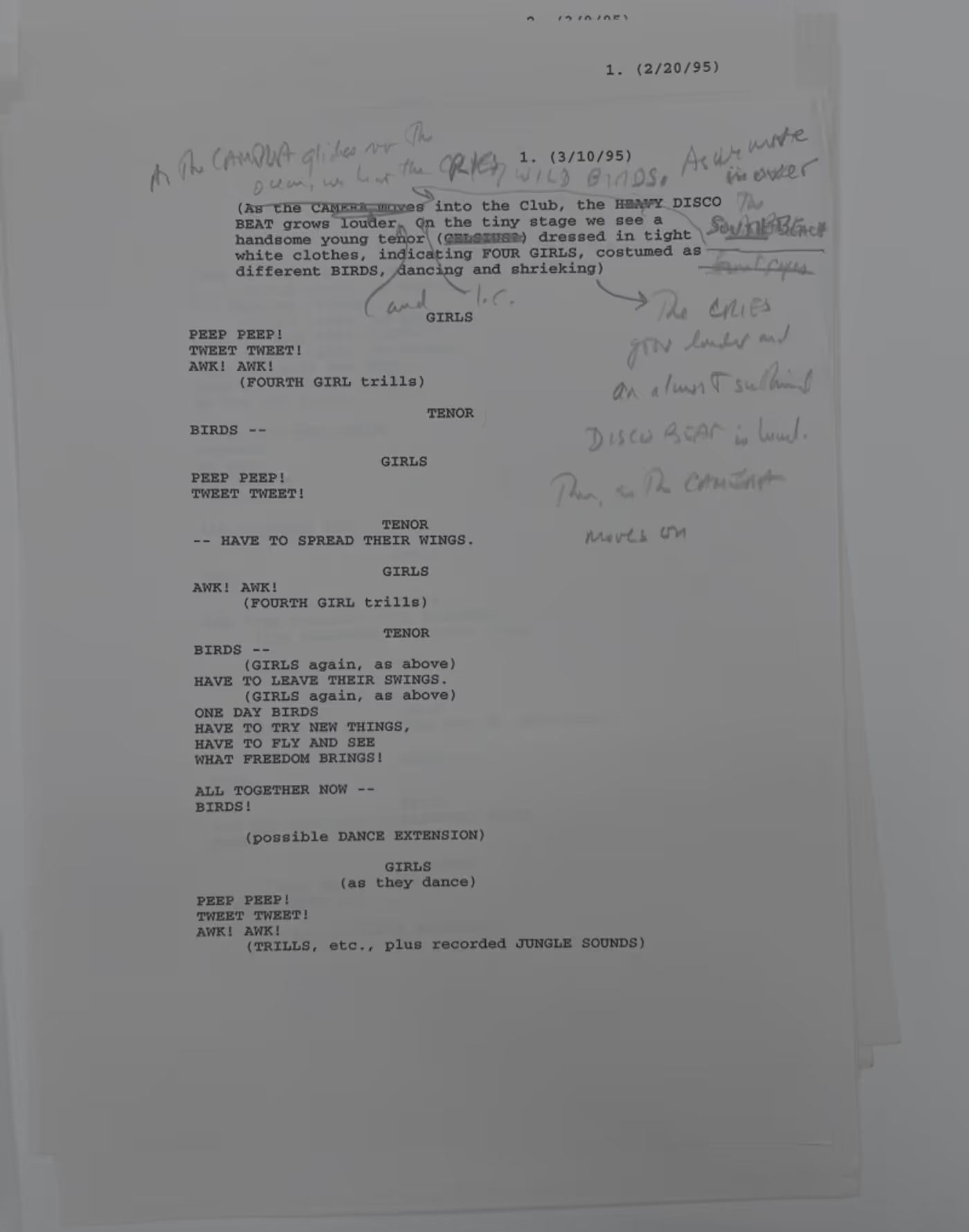

Not only is Sondheim’s work on “Little Dream” and “It Takes All Kinds” chronicled in his The Birdcage files at the library, but so are several other song drafts and ideas. A full song called “Birds” was written for the character Celsius (the dancer who blows a distracting bubble with his gum during rehearsal) and four girls to perform. Sondheim was the master of content dictating form, and for that reason, it should come as no surprise to see him note a “heavy disco beat” in the song—although it’s certainly not a genre of music that we regularly associate him with!

“Birds” was an early idea for an opening number that never made it out of Sondheim’s notebooks. It was meant to introduce the audience to the drag club where the film is set by imagining the club’s entertainers as a variety of different kinds of birds. In the production number, the bird-dancers learned to freely spread their wings and fly, an apt metaphor for one of the story’s themes. Because “Birds” was forsaken for the more direct “It Takes All Kinds”, which was eventually cut altogether, the song is doubly esoteric.

There was also a completely different early version of “Little Dream”. The earlier draft of a solo for the character of Starina was called “A Woman of the World”, which Sondheim imagined to be a torch song in the style of the Great American Songbook classic “Love for Sale”, bringing to mind Judy Garland and Marlene Dietrich.

Sondheim also workshopped song ideas for an original duet between Armand (Williams) and Kath (Christine Baranski) that would have been instead of their “Love is in the Air” moment. For this song, he imagined Williams would utilize a number of comedic props, with Baranski’s assistance. Sketches also exist for a song called “Surprise!” which would’ve been for Starina.

3. Sondheim was unintentionally depicting Jonathan Larson’s bohemia while writing parts of Merrily We Roll Along.

I spent years researching The Jonathan Larson Project at the Library of Congress, and visited while working on the tick, tick… BOOM! film as well, so Jonathan Larson is on my mind whenever I’m there. It was particularly fun to feel like Larson, who counted Sondheim as a hero and mentor, was making serendipitous appearances in the Merrily boxes. Some of this was because Sondheim and Larson had the same reference points for certain historic eras, and some was because, in trying to write about artists struggling at the beginning of their creative careers in New York City, Sondheim hit on a topic that a lot of Larson’s work explores as well. Obviously, none of the connections were purposeful but they felt special to discover, nevertheless.

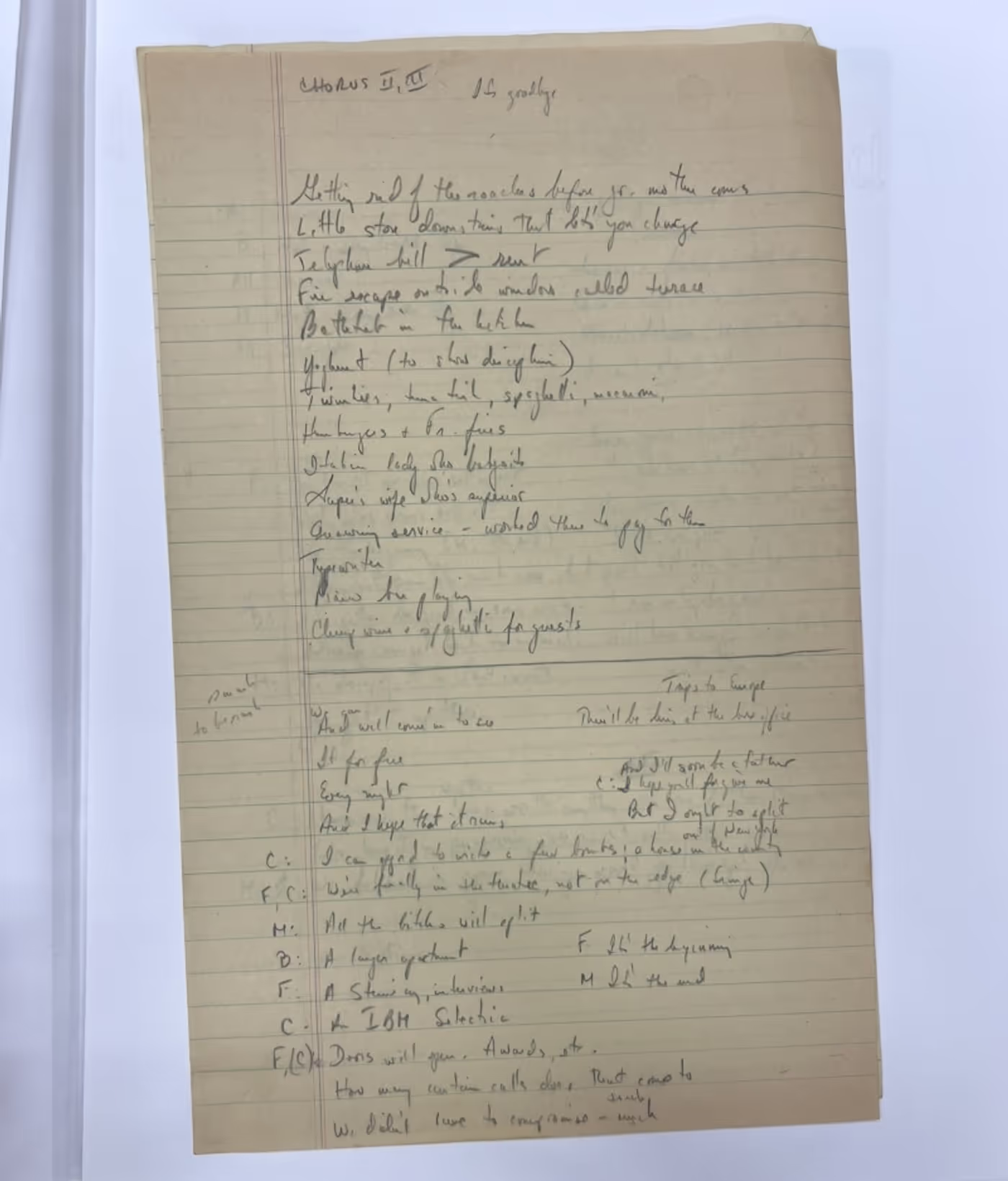

One of Sondheim’s Merrily work pages lists:

Getting rid of the roaches before your mother comes

Telephone bill > rent

Fire escape outside windows called terrace

Bathtub in the kitchen

Twinkies

Piano bar playing

Cheap wine and spaghetti for guests

Is this Frank, Mary, and Charley “Opening Doors”, or is this Jonathan’s “Boho Days”?

Both Antonioni and Kurosawa were in drafts of “The Blob” in Merrily and appear in “La Vie Boheme” in Rent. While in “The Blob” the filmmakers are shouted to denote a kind of empty-headed name dropping, the “La Vie Boheme” crowd, in a scene that takes place more than three decades later, reclaims the names of the artists and celebrates their alternative contributions. Of course, the bohemians roar Sondheim’s name as well.

There are a few other uncanny intersections between Larson and Sondheim, but I’ll let other scholars discover some for themselves…

Larson was 21 years old when Merrily opened. Years ago, I spotted on one of his notebook pages where he had scrawled “We’re opening doors!” The two writers are linked in ways that neither of them knew.

4. Many songs were originally given placeholder titles in Sondheim’s outlines—and some of these persisted for awhile.

When outlining what he felt the song trajectory of a given musical should be, Sondheim often created a placeholder title for a number. Often, these titles remained for many subsequent drafts of the song. Watching the eventual final song title emerge through rewrites is a delight.

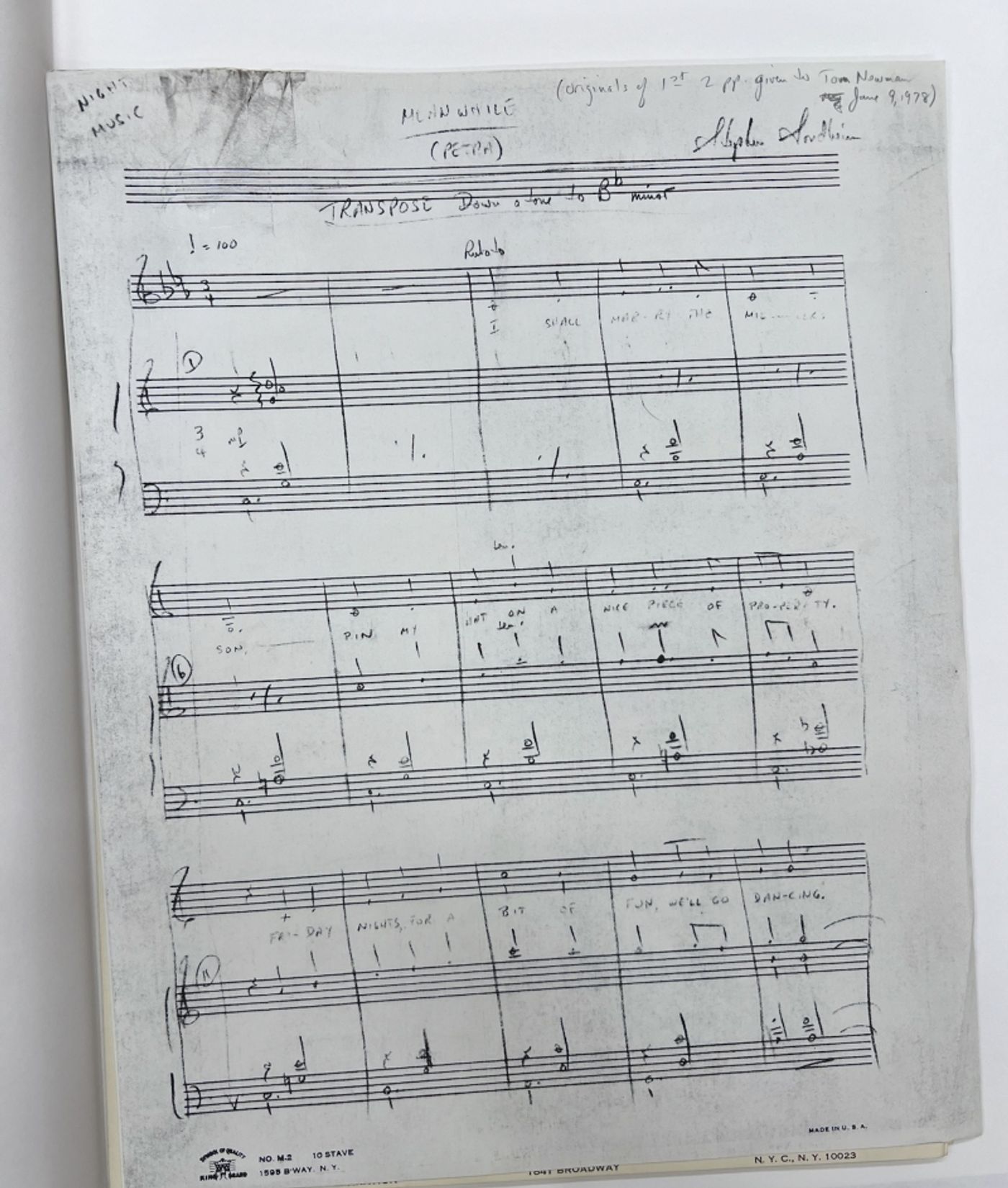

“The Glamorous Life” from A Little Night Music was labeled “Mothers and Daughters” while “The Miller’s Son” was labeled “Meanwhile”. The placeholder title “Lullaby” was used for “No One Is Alone” from Into the Woods. The title number from Sunday in the Park with George was at times referred to as to “Dot’s Song” or “Being Painted (Worse Things)”. For awhile, “Ladies Who Lunch” from Company was simply “Drinking Song”.

Perhaps my favorite is that Sondheim’s August 1980 outline of songs he intends to write for Merrily We Roll Along includes “You Have To Give ‘Em Something To Hum (pounding the pavements)”, which would later solidify into “Opening Doors”. And along with that, before “Putting It Together” from Sunday in the Park with George was named as such, it was labeled “Have To Keep Them Humming”!

5. Sally and Phyllis did not get dressed for dancing at Rector’s.

Of course, Sondheim made sure every reference he ever made was correct for the characters, story, and time period at hand. It was particularly delightful to see the evolution of his score for Follies on paper, as he made every memory of the characters at the reunion vivid. Every word is meant to give us a world of information. One of my favorite instances of this comes in the song “Waiting for the Girls Upstairs”. In several early drafts, Young Sally and Young Phyllis chide Young Ben and Young Buddy that they had promised to take them dancing at Rector’s.

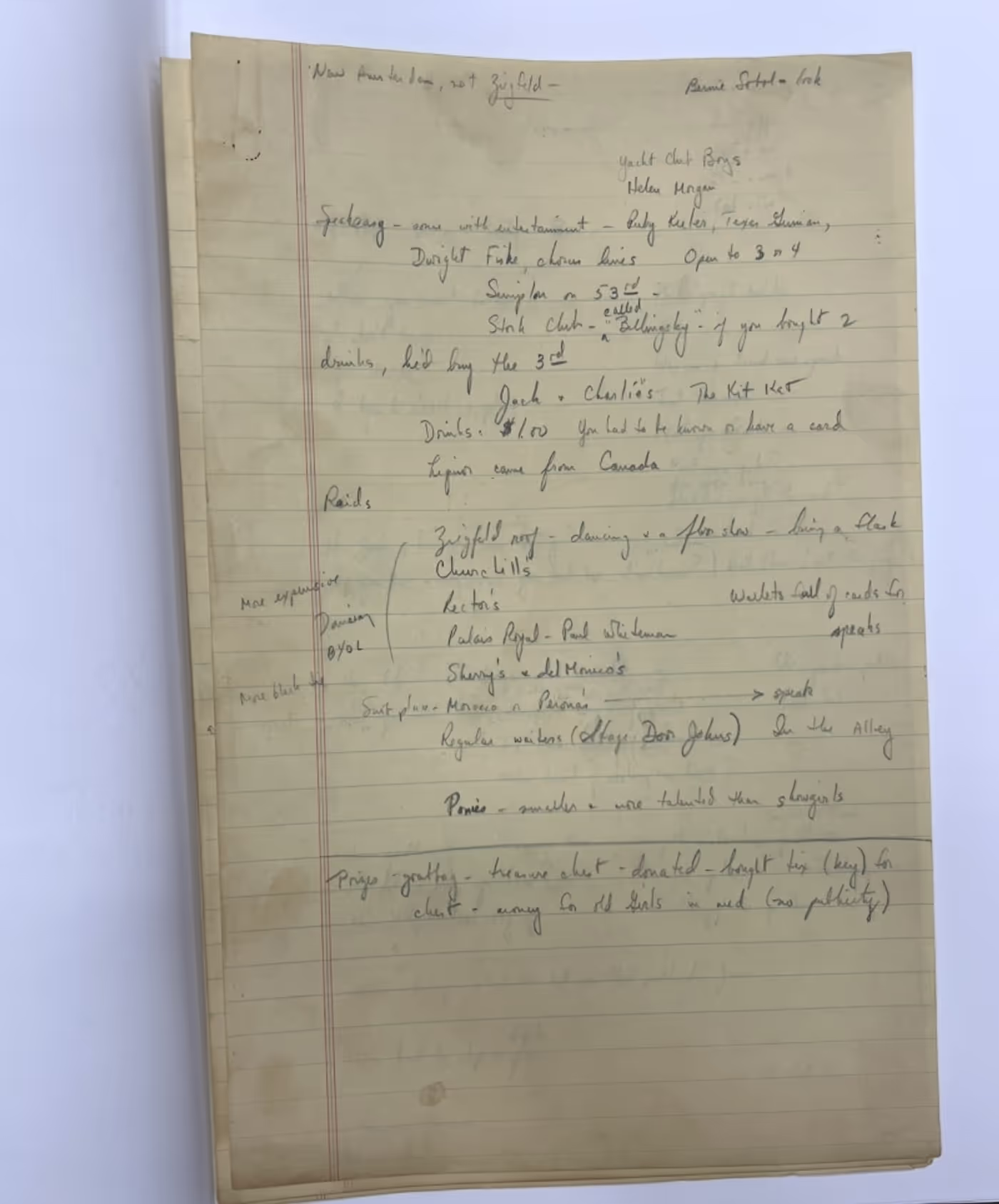

Sondheim often used placeholder references while writing until he could deliberate on the exact reference he wanted. Rector’s would have been exactly where showgirls like Sally and Phyllis wanted their dates to take them—but in the early 20th century, not in 1941, when the flashback takes place. Thinking about where the showgirls of 1941 might go, Sondheim listed venues like the Stork Club, The Kit Kat, Jack and Charlie’s, and the Palais Royal, noting details about each spot like if they used to have a different name or what their policies on liquor and dancing were.

Old drafts of the song note that Rector’s is “snotty” before Sondheim switched the locale. While he could have selected a historic watering hole of the early 1940s that we all still know by name today, he instead chose the more obscure “Tony’s”. Short for Tony’s Trouville, the East 52nd Street venue was precisely where young chorus girls who aspired to be part of the glamour of high society would’ve wanted to go dancing. The elite speakeasy lived a series of lives, including years as “Tony’s”. In the years just before Follies, it had been demolished, with a glass-windowed office building now towering over the entire block—mirroring the themes of the musical, with its pending theater demolition.

Another notebook page where Sondheim was working on “Waiting for the Girls Upstairs” shows him free associating phrases from the time period of the Weismann Follies hey-day. “Park yourself”, “noodle”, and “chew the fat” are in his list which eventually led him to a song filled with dynamic and time-period accurate colloquialisms like “okey-dokes”, “there in a jiffy” and “slipped a fin”.

There aren’t enough superlatives to describe the wonder of poring over the Sondheim Collection at the Library of Congress. Massive thanks go to Sondheim and his team as well as the team at the library for giving us more to see.

Check back on Sunday, November 9 for more Sondheim discoveries in Part 2!

All images (© 2025) and the music and lyrics of Stephen Sondheim are reproduced with the permission of the Stephen Sondheim Trust. All rights reserved.

Comments

Videos