Back to Nubia: Stories from the Making of AIDA After 25 Years

Heather Headley, Adam Pascal, Sherie Rene Scott look back on the journey of the beloved 2000 musical.

Aida opened on Broadway on March 23, 2000 after out-of-town tryouts in Atlanta and Chicago. The musical ran for 30 previews and 1,852 performances on Broadway before its final bow on September 5, 2004.

In honor of the show’s 25th anniversary, BroadwayWorld spoke to stars Heather Headley (Aida), Adam Pascal (Radames), Sherie Rene Scott (Amneris), Schele Williams (Nehebka), as Thomas Schumacher (original producer and Disney Theatrical Group chief for its first three decades), lyricist Tim Rice, and book writer David Henry Hwang to compile an oral history of the show’s early days, transition to Broadway, and legacy beyond the boards.

Thomas Schumacher (producer): Let me tell you exactly what happened.

Tim Rice (lyrics): I think it was Michael Eisner's idea — or it actually emerged creatively from Disney.

Schumacher: We did a thing at Disney Animation called The Gong Show, based on an old television game show where people would come on and perform like a talent show. But if anyone on the panel didn't like you, they could gong this gong, and you had to stop performing. So we nicknamed this pitch session The Gong Show.

Rice: Elton and I had had a success with “Lion King,” and I think — you'd have to check this out really — I believe they had the idea that they might do an animated cartoon, an animated feature of Aida's story with maybe me and Elton doing the songs.

Schumacher: A spectacularly talented artist, a woman named Lisa Keene — who had been the first female head of the background department on my first movie, “The Rescuers on Under” — she brought in a children's book written by Leontyne Price [about] Aida. Lisa pitches it as an idea for animation. We buy the idea.

Rice: They had such success with “Beauty and the Beast” and “Lion King” on stage, and indeed “Aladdin” later, and they'd set up Disney Theatrical, which was doing quite well, and they thought, “Well, why don't we, for once, have a go at doing a show straight away without the film first?”

Schumacher: I was reading it, and this was in the spring of 1994, and I'm reading thinking, “I love this idea, but this is so wrong for animation.” I'd given up this idea.

Rice: So I think at some point, “Aida” got changed from cartoon to stage show, which actually meant that we were required to do a lot more than we would have been.

Schumacher: I think we're at June 19th — I can check the date for you — We have just premiered “Lion King” at Radio City Music Hall. The next morning, Michael Eisner, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Peter Schneider, myself, Elton John, and Tim Rice, and maybe Elton John’s then manager John Reed — I'm not sure — were in the Disney offices. We're just talking to Elton about the future and how great it went and everything. And everyone had this idea that Elton could do another movie. And he says, “I don't think I really want to do another animated movie. I just did that. But didn't you guys just a couple of months ago open ‘Beauty and the Beast’ on stage?” Michael Eisner turns to me and says, “Tom, what do you got?” And it just hit me. I said, “What about something based on ‘Aida’?”

Rice: Elton was quite happy with the idea. I don't think he, like me, really knew the story. I'm not quite sure where it came from. I mean, Verdi must have based it on something.

Schumacher: So before “Lion King” was ever discussed on the stage, “Aida” was in development.

Heather Headley (Aida): When I auditioned for “Lion King,” I remember my agent at the time, she said to me that the casting director had said to her, “So we really are looking at her for this ‘Lion King’ thing, but, Disney also has this other show, ‘Aida’ that they're looking at in the future, and she might be good for that, but let's just focus on ‘The Lion King’ right now.

Sherie Rene Scott (Amneris): I was in “Rent,” I think, and I had an audition, and it was a different creative team. It was when Michael Eisner was the head of Disney and Tom Schumacher was there and Peter Schneider … I think I thought Tom Schumacher was just one of the kids. I didn't even know he was one of the producers until, I don't know, maybe a year into the production.

Rice: Anyway, it was a good story, and we began working on it with Disney's help as producers. That was how it all began, but I'm not really sure whose idea it was. I mean, it wasn't mine and it wasn't Elton's, but I think it was perhaps Disney.

Schumacher: I would argue that's when it was born, because Michael said, “Let's do this.”

Then called “Elaborate Lives: The Legend of Aida,” preview performances at Atlanta's Alliance Theatre began September 17, 1998, ahead of an official opening night October 7. Plagued by technical difficulties, the show received mixed reviews — something that would become a recurring theme throughout its various incarnations.

Schele Williams (Nehebka): 98% of us who did the Broadway incarnation were not a part of that. There were only maybe two ensemble members, and Heather and Sherie.

Rice: Heather Headley, right from the word go, was brilliant.

Scott: I don't even know if it was called “Aida” then. I think I just remember somebody's wife was like, “We can't call it ‘Aida,’ we have to call it something else.” So they called it “Elaborate Lives.”

Rice: The Atlanta version, I quite liked it. But it didn't quite work, I think the set was a problem.

Schumacher: I'm sure you've heard this, where we had to stop the show.

Rice: They had this great idea, and it was quite clever, of a pyramid which turned into lots of things, but it was — it took up so much space and it was somehow — it's a strange thing which seemed simultaneously too big and too small. It was a bold idea, which didn't quite work, practically.

Headley: It was supposed to open and close and become our tomb and become the palace and become everything, and I think it would have been amazing if it could. It just wasn't coming together. If it worked, it was a state of the art, crazy pyramid. It ran on lasers. It did not run on tracks. The gentlemen who did Tower of Terror and stuff like that, they were working on it.

Rice: Interestingly, almost the best night in Atlanta was when the set completely refused to start.

Schumacher: Alan Hall, a historically important stage manager on Broadway who also stage managed the Tony Awards every year, had actually been trained in the British Army as a bomb guy. He had nerves of steel.

Headley: I think it was the first night of previews or something like that, either the first night of previews or opening night and Elton was there. Elton was there and it shut down.

Schumacher: At the first preview, we're 20 minutes into the show and the whole set just stops. We're at the Alliance. Kenny Leon is the artistic director at the time.

Rice: I mean, there's always problems with the set. The pyramid, which was turning into a boat or turning into a temple, which was great in theory, but you get stuck and then blokes would come on with old-fashioned oil cans trying to fix it.

Schumacher: I run back to the stage to the booth where the stage manager is calling the show, and I say, “Alan, what are we going to do?” And he goes, “Excuse me?” I said, “What are we gonna do?” He says, “No, no, no, Tom, it's after 8 o'clock. Get back to your seat.”

Headley: They had taken it so seriously, these engineers, because they — I remember one guy said to me, “Your work is from 8 to 11 at night and my work starts at 11 o'clock when you leave because I have to make this work.” And they would work all through the night on it, on trying to make this pyramid work.

Rice: And one night, they kind of gave up.

Headley: That bad boy would not work. It just would not work.

Schumacher: Michael Eisner says, “What's happening?” And I said, “Alan Hall is in charge.” So we said, “Ladies and gentlemen, if you'll join us in the lobby, we'll be back with the show in a minute.”

Rice: It was quite clear that the pyramid was not going to work that night at all. It was quite early on, they'd only done about one scene.

Schumacher: Then we all gather, and we're told the thing cannot move. It's stuck in the middle of the stage, and there's hydraulic fluid everywhere, which had been coming up during rehearsals and previews and stuff, and it was just like people slipping and falling. It's horrible. And Alan says, “Well, we're going to present them the show concert style.”

Rice: So the director, Rob Roth, got everybody, all the actors, on stage in a semicircle. There wasn't much room because of the effing pyramid.

Headley: So Disney put us on chairs in front of it and we sang the show. We did the show on chairs in front of it.

Schumacher: And so we did boys on stage right, girls on stage left, and all the principals in the middle, whatever costume they were last wearing. And the audience comes back in.

Rice: But they all sat and the orchestra was still there, obviously, bashing away, and they sang it and spoke it almost as if it was a radio play, and it worked wonderfully. The audience really got into it and the songs were so good, and I thought, “Maybe we don't need a set at all.”

Schumacher: Heather gets up there and she sings “Easy as Life.” And the audience, who've been through hell already, leap to their feet screaming, leap to their feet.

Scott: We had to perform this show so many times in folding chairs. Things would break down and we'd have to do concert versions, and I think that really bonded us as a group of people. They saw Heather and I staying positive and making fun of the ridiculous situation, but still staying upbeat.

Rice: It got quite good reviews that I can remember in Atlanta.

Headley: I think at the end it got a standing ovation and I think that's when Disney said, we know we have something here.

Schumacher: And Michael Eisner turned to me and said, “We do have a show here.”

After the tumultuous Atlanta run, which concluded in November 1998, most of the show’s creative team was scrapped, including director Robert Jess Roth and set designer Stanley A. Meyer. They were replaced by Robert Falls and Bob Crowley, respectively, and Wayne Cilento was brought in as choreographer. Headley and Scott were two of the only cast members to retain their roles.

Schumacher: Now this is where it gets tricky, but we end up making a change.

Headley: I remember thinking this is a scary, scary place to be in, because that Sunday night we had closed the show, and that Monday morning, it was a clean slate. It was a very, very clean slate.

Rice: Disney were a bit ruthless and they decided to eliminate an awful lot of people involved with it, which was unfortunate really.

Schumacher: We changed teams completely.

Rice: But the only people who survived the cull were really me and Elton, and Natasha Katz, a brilliant lighting designer, but everybody else, most of the cast members, got the chop, which was, you know, sad. But I was amazed Disney wanted to continue with it.

Headley: It was a whole overhaul. Everybody was gone. They had just said, “You and Sherie will remain.” Even our castmates had to re-audition, and some came with the new cast, but they had to re-audition because at that point, like Wayne Cilento and Bob Falls — they had a different look of what they wanted, right?

Schumacher: Between January and October, we designed, wrote, and built — and David Henry Hwang came on — and we built a whole new show and premiered it that following October. Who's ever built a show that fast?

David Henry Hwang (Book): I think I was brought in to rewrite the book. But ultimately, Bob Falls and I ended up doing that task together. We worked on it, gosh, I would say for about a year before we went into rehearsal for the Chicago production.

Headley: They put me back in “Lion King” for three months.

Hwang: “Aida” was my first experience having a musical produced.

Schumacher: We go back into rehearsal, and then we begin the show in Chicago. And it's a rough ride. Elton can't come until the third preview.

Headley: The funniest part of this is that through the whole thing, because of my relationship with Disney at the time and because of my relationship with [Thomas] Schumacher and those gentlemen, I was always in the confidence that it would be OK.

Hwang: It was not an easy process, and I think you've talked to Heather and so you probably know that it was hard to wrestle this show into shape.

Headley: The beauty with Disney – I love it when they allow us to be collaborators and allow us to be on the front lines of it. I remember them saying, we have Radames — and Radames is Adam Pascal.

Adam Pascal (Radames): I wasn't looking to do another musical certainly, but this opportunity came along and I really was just drawn to it by the idea that it was an original score written by Elton John — and because it was only my second show.

Williams: Adam and Sherie and I did “Rent” together. When I came into the cast, those were the only two people I knew.

Scott: When Adam Pascal was brought on, then we just were all like, "Let's go! Let's go with this.” I loved Adam from “Rent.” He was one of the cast members who was really nice to me and kind — and he’s secretly hilarious.

Pascal: It didn't even sink in in any way that was relevant that there was a prior production of this show like Atlanta. I didn't really even get what that meant. I was just super excited at the team that they had assembled, obviously Heather and Sherie and Bob Falls and Wayne Cilento, it was a really high caliber, A-list team. And I felt really honored and grateful to be part of it.

Headley: I remember sitting in the room and having Bob Crowley and Bob Falls, in essence, present to us what they were thinking. So I do remember — and this is before Chicago — but I do remember being the audience and seeing that first scene, and it's the museum and I'm like, OK. All right, we're doing this in a museum. I don't know how you're gonna do that.

Scott: I will say that when they brought Bob Crowley in for the design on the second part of the team, it really classed up the joint, as they say. It really made sense dramaturgically, as well as stylistically, and beautifully rethought the whole thing, and just his visionary sense and his ease, and his class, and he was so great to work with.

Pascal: There were a lot of those changes going on during the process, and some of them were frustrating. Things that we wanted to make work just weren't working.

Hwang: This was particularly intensified by the fact that we generally were not well reviewed or received in Chicago.

Scott: I think that we trusted the new vision. Bob Crowley helping with the visual aspect and the scenic and costume aspects of the show really gave it a cohesive feeling, a vision. It was more timeless than Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Headley: I really did enjoy that period of rethinking the whole show, and seeing it from a different perspective. This reincarnation kind of thing and how these characters meet in the future and, and everything like that. So it was fun, still scary, you know, taking it to Chicago.

Scott: So I think that's what really helped coming from Atlanta to Chicago, and also that we all really loved each other and had a lot of fun.

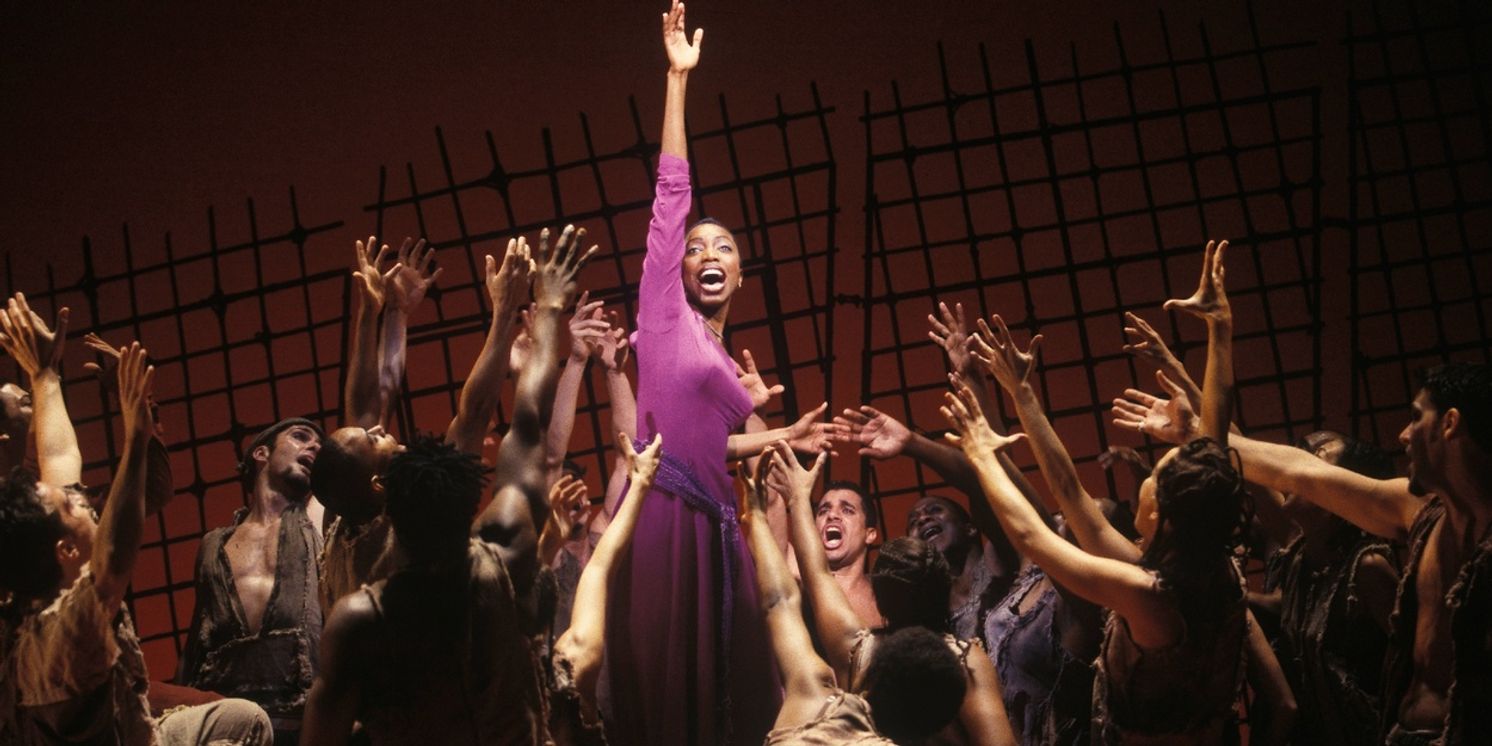

%20Ensemble%20of%20Elton%20John%20%26%20Tim%20Rice's%20AIDA_%20Photo%20by%20Deen%20van%20Meer.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

After overhauling the creative team and, subsequently, the show, previews at Chicago’s Cadillac Palace Theatre began November 12, 1999. The first preview went off without a major hitch. But the second was not without incident.

Headley: Well, we had the accident in Chicago.

Pascal: I mean, if you've spoken to Heather, I'm sure she's talked about the fall that we had on stage.

Scott: Of course, from Chicago, I remember [the] tomb falling with Adam and Heather inside of it. That was awful.

Rice: There was the thing when the tomb fell, and made quite a big story.

Schumacher: I did 21 of the animated movies, you know, that I worked on with all those people, and 19 of them were done simultaneously theatrical. So by the time we're into this [“Aida”], we're making animated movies and doing all these stage shows. The premiere of “A Bug's Life” was happening the day after the first preview of “Aida.” So Peter Schneider and I, who are producing “Aida,” we did the first preview. OK, we got through that. We take the jet back to LA. We go to this premiere.

Pascal: I don't know if she described to you what happened, but I'll give you my description because I tell this story all the time.

Headley: I know my therapist says I can't talk about it. It brings up too much.

Schumacher: And my driver comes in because he's got a phone call in the car and he says, “There's been an accident on your show in Chicago. I think you need to come to the car.” And I excuse myself, I don't say anything.

Pascal: So we're doing the moment when the two of us are dying and we're singing to each other, and it's this very intimate moment. All of a sudden, this thing that we're in, which is like 20 feet up in the air, drops just like a foot or two feet while we're singing. Just long enough for the two of us to go, “Oh s**t,” right? ‘Cause we knew it was coming.

Rice: It fell to the bottom of the stage and they tumbled out and they didn't move. And for a minute we thought, blimey, what's happened here?

Schumacher: I go, and we've been told there's a really big accident and Heather and Adam are seriously injured is what I'm told.

Pascal: We hit the stage, we then fall out of this tomb that we were in, and then onto the deck of the stage. So now we're actually laying on the stage. And I learned this years later, but our mics were still on, and the stage managers could hear us talking and hear me talking to her, while this was going on.

Scott: I was doing a fast change right behind it. I could only see from where my position from behind the tomb was, both of their bodies on the floor.

Rice: I think they were just being very sensible, not moving, because they were sort of enveloped in each other, and I suppose each of them might have thought, well, if I move I might hurt the other person or whatever.

Schumacher: There's now a news report out there that Heather has fallen 32 feet from a basket and hit the deck and broke her pelvis. This was in the news. Of course, this did not happen.

Pascal: It took a second for everybody to realize — especially the audience, because this was our second preview and this was our death scene — that this wasn't supposed to happen.

Rice: So that was a bit of a, to put it mildly, frightening moment, and it was just before the very end of the show. I'm sure I heard on that occasion the immortal thing, “Is there a doctor in the house?”

Pascal: My memory of this is cloudy, but a lovely young woman came up on stage and she was like, “I'm a dermatologist, but I'm a doctor.”

Rice: Fortunately, neither Adam nor Heather were injured. I mean, they were shocked. And there were changes made to the way that that scene was done.

Schumacher: Adam cracked a rib and Heather banged up her buttocks or something. And it was horrible.

Pascal: They took us both away to the hospital, in ambulances, in our full costume, microphone, makeup, the whole deal. It was really quite an experience, and we were both hurt.

Rice: That certainly got the show some publicity.

Scott: Of course, they ended up being okay, but they got taken to the hospital and it was a bonding experience. I just hung out with them at our residence for like the next two days, I think. And to see all the Disney guys lined up just teary-eyed. You get to see how much everybody really cares about everybody.

Pascal: The experience itself was terrifying and exciting at all the same time, and, you know, all these years later has always made for an interesting story.

Schumacher: But nobody spent a night in the hospital, they all came home. But obviously they couldn't go on the next day when Elton was supposed to be there.

Rice: So that was the major tech problem just out of town.

Schumacher: Now Elton can't come until opening night.

Still, the show went on, plagued by uncertainty and fraught tensions. Two preview performances were cancelled November 14, with Headley and Pascal returning to the production November 18. “Aida” opened December 9, 1999, to mixed reviews. Schumacher ultimately called an all-hands-on-deck production meeting to discuss the show’s path.

Schumacher: So the show opens, it gets, you know, whatever reviews are said about it.

%20Heather%20Headley%20Adam%20Pascal%20in%20Elton%20John%20%26%20Tim%20Rice's%20AIDA_%20Photo%20by%20Joan%20Marcus.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Rice: It didn't really get great reviews in Chicago, to be honest.

Schumacher: So the team is still kind of at each other's throats, right? But the show is running.

Williams: In 1999, we opened the Cadillac Palace, and that's where we all spent the millennium.

Schumacher: I used to live on Central Park South, and I go have lunch with the late Isabelle Stevenson of the American Theater Wing, who had been my pal for a long time. I'm having lunch with her and, and she says, “Well, how's it going, dear?” And I told her the whole saga, and I said, it's just a mess, and no one's talking to each other, and it's just not working. And she waves her little finger at me and says, “Do your job.”

Williams: We were all there in a bar at the Cadillac after our show and celebrated Y2K.

Schumacher: I said, what are you saying? She goes, “All the time on my TV show, 'Working in the Theatre', people go out of town, they come, they prep their shows, they come in, and then they never do anything between the times, and then the shows don't work. It's over and over. Do your job, get everyone together and work on it.” I literally walked back to my apartment, sat on the floor. I remember exactly where I was, sat on the floor on the phone. I called Stuart Oken, who was so central to the creation of “Aida” and “Lion King,” who used to be here at Disney Theatrical, and I called Stuart and said, “We need to get everybody to go to Chicago, we take that conference room off the mezzanine. We're going to put the whole thing up and everyone has to come.” And Stewart gets everyone on board.

Williams: We're like, either the world's gonna end or it's not, but we're here.

Schumacher: People flew in for this. And I said, “Folks, here's the rules of the game today. You get to say and need to say whatever you think about other people's work, and you have to say what you think. I cannot be the person who's hearing this. Tell the whole room. And if you're going to participate, you have to be willing to let people say it about you, your work in front of you.” The room was at first a little tense.

Rice: The decision, which I think I have to brag here was mine, to make “The Gods Love Nubia” at the end of Act One – It wasn't before.

Schumacher: The story is all up on the wall, cards of scenes in white, songs in blue kind of thing, which is a technique we developed with [Disney] animation. So you're looking at it, like what's not working? And I said, “Who wants to go first?” And Tim Rice, God bless him, said, “Well, I think one of the best songs in the show is Gods Love Nubia. It's buried in the middle of the second act. There's no big excitement at the end of the first act. All we know is exactly what happens at the opera: They capture Amonasro, Aida's dad, and they bring him in and then everyone goes, ‘Yay,’ and we're supposed to cheer for this scene that is about a horrible thing happening.” He said, “Why don't we instead take that same moment, but show it from where the Nubians are living, same moment in time. He's been captured. But we see their point of view, not his.”

Hwang: In Chicago, “Gods Love Nubia” was in Act 2, and Tim had the idea that “Gods Love Nubia” should close Act One because in Chicago we had another number that closed Act One — “Our Nation Holds Sway” — which was the sort of our version of, where the king Amonasro gets kind of paraded as a prisoner, before the Egyptians. It was a pretty bleak way to end the act.

Schumacher: What a brilliant idea. This is the single biggest, most important note.

Rice: I can't remember what was the end of Act one, but, that really worked because it was a great choral number.

Schumacher: Bob Falls, who I still love, he had the courage to say, “Tim is absolutely right.” And Bob Falls went over and moved the pin and moved “Gods Love Nubia” to the end, and we cut the song that was the end of the first act.

Hwang: Tim had this idea that “Gods Love Nubia” would be a much more uplifting outbreak, and he turned out to be 100% correct. “Our Nation Holds Sway” is no longer in the show.

Schumacher: There was a sense that Radames had no character. And so Bob Falls says, “I think that we should have a song there that establishes what Radames and his men are doing.”

Pascal: I'm trying to remember when this in particular happened. It must have happened between Chicago and New York, I think.

Schumacher: Elton said, “l’lI write a new song.” It was that easy.

Hwang: “Fortune Favors the Brave” was not in the Chicago version. We all decided that Radames hadn't been established sufficiently as a character for the audience to understand and embrace and sympathize with. So, we sort of came up with what is sometimes described as not an “I want” song, but an “I have.”

Pascal: Anyway, the song “Elaborate Lives” used to be an Aida song that she sang to Radames. At a certain point, and I can't remember exactly when this happened, they realized that I didn't really have any good songs.

Schumacher: Heather was not happy about this. I'm sure you've heard about that.

Pascal: Whenever we did it, Heather was not happy at all that they took this awesome song from her and gave it to me.

Schumacher: So she's very upset. But we were trying to do everything we could to get the character of Radames to be worthy, because she [Headley] built the character so deep, so we needed that character Radames to be worthy of her.

Pascal: We had a great chemistry on and off stage and really, really adored each other.

Schumacher: Now we're down to the fashion show. Every lady was wearing the same dress but a different color. And I said, “Bob, this just isn't, it's not a fashion show.” And there was some excuse or whatever. Barbara Matera was building the costumes. And I said, “What I want is everybody to have a different costume. Every dress should be different, and the swings should have their own so that we don't have to repeat anything.” Wayne says, “I can create choreography for each one of the looks.” And so the whole number gets reinvented. But Marshall Purdy, who was general managing the show, said,”Well, we don't have any money for that.” And we're in the room with everybody and I said, “Marshall, what's the number we have held for an opening night party?” He says, the number. I said, “Bob, can you build it for that?” I said, “Marshall, we're going to give everyone a glass of champagne in the balcony, and we're going to have a great fashion show.” So that day, we tore it apart and put it back together again.

The cast and crew traveled back to New York City to re-rehearse the show in preparation for opening night on Broadway.

Williams: We re-rehearsed the show. We went back into full-scale rehearsals back at 890. There were a number of things that the creative team learned from the Chicago production, and there were a number of changes that they wanted to put in. So, we finished our run, we came back to New York, we went back into rehearsal, we implemented the changes, and then we went into a tech process.

Schumacher: We get to New York, and we're hanging on a thread, trying to get this thing done.

Williams: I think if you ask anybody, they'll tell you Wayne Cilento was the unsung hero of the production, hands down.

Headley: Wayne Cilento, God bless him.

Williams: Wayne really kept such a positive energy as we were in the trenches of long days. We had already done a production. We're back in rehearsal, we're making changes. We had tough reviews in Chicago, so we knew the stakes were high for us to figure some things out. Wayne was extraordinary in his leadership, and his belief in us, and all the ways that he kept on just infusing this positivity.

Headley: I still have this special place in my heart for him.

Williams: We would just circle up and then we'd all be like, “OK, we're gonna do it. We're gonna get back in it.” “Get back in it” was such a big part of our mantra as a cast. There's a little something in the show that most people don't know. At the top of the second act, we did this like, “gehbahiah,” which is a vocalization that we said, but it was based on “get back in it.” It was the way that we all kind of just rallied each other.

Scott: [Cilento] just really fires up everything, and I still use his “get back in it” phrase. He and Bob were the biggest assets to the team, and I thought things took fire then.

Williams: It's so funny because other productions do things and it's like, you've no idea what that means. That literally is a vocalization from us just saying to each other, we got this, we got this, we got this.

Schumacher: We're, I don't know, preview 2, 3, 4, somewhere in there, and Elton comes to see all the changes we've made.

Scott: They were wise to keep it going because it was a beautiful piece, so I just really believed in it. I believed in what it was saying.

Schumacher: We're 20 minutes in the show, and we've already done the pool, which is that great effect. And Elton gets up with like two other people and walks out of the theater in the middle of the first act.

Williams: We were all on pins and needles because we were all like, we need this show to work. So there was an excitement. We were incredibly focused.

Schumacher: I put my hand on Tim's knee and I say, we're not leaving. And we sat there. My head is exploding. So we get to the intermission and I say, “Tim, we have to go up to the St. Regis Hotel where Elton was staying.” I get to the room and it's Elton on a sofa surrounded by everybody, and then we had, which I will not go into for you on record, but we had a very reasonable — started very angry — but a very reasonable conversation about the show and walking out and what that meant. And I said, “When can you come back?” And he said, “Well, I'm gonna be in the area on this date, I can come back then.” And I said, “Great. We'll have everything ready and you'll come back and watch the show again, and I promise you, what you didn't like will be fixed.”

%20Sherie%20Rene%20Scott%20and%20the%20original%20Broadway%20cast%20of%20Elton%20John%20%26%20Tim%20Rice's%20AIDA_%20Photo%20by%20Joan%20Marcus.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Elton John returned to the Palace Theatre to see another preview of “Aida” and raved about it, apologizing to the cast for walking out. He became an ardent supporter of the production and participated in talkbacks for Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS. Then, after 30 preview performances, “Elton John & Tim Rice's Aida” opened to mixed reviews on March 23, 2000.

Headley: I think I was scared to death.

Rice: We went into Broadway and it got quite well received, but the public seemed to love it and it ran for quite a long time — best part of 5 years.

Scott: I remember doing the work and creating the work with people and and the feelings and I don't remember the parties, I guess. That's just a goal you're getting to, and it's more for other people than it is for you, because you know, we're running on fumes by that point and you want it to go well for everybody.

Headley: I knew that Sherie's part was fun. I knew the arc that she had. I knew how sad this was for her, so I understood her role perfectly. I understood Adam and his role, but I just knew that I was bringing all of this to the table, but I didn't know how people would accept her. I really didn't.

Scott: I just loved everybody and my work environment was really a sanctuary for me in ways that I couldn't tell people at the time, so I just remember being happy to be with people. I just remember really being happy to be around other people on opening night.

Hwang: This production team took a lot of risks, made some bold choices, and it really felt like they paid off on opening night.

Pascal: When the reviews came out, I didn't get good reviews and I was shook by that because my only experience was “Rent” where everybody loved me.

Headley: I had chosen not to read the reviews. I had said to myself that I wouldn't read the reviews, so I didn't know.

Pascal: I never read another f***ing review after that.

Headley: So yeah, that night was very scary, and the next morning was incredibly scary because I remember thinking, I knew what the New York Times could do to us. I knew like Chicago Tribune and all of them, you know, you're just sitting there going, my life could be over in 3 hours.

Pascal: With the reviews after that, I was like, f**k this, I never want to go through this again and it wasn't until many years later that I originated another part. It was really difficult and painful, and I see what other people go through. I just don't see the point.

Hwang: Once we got the show to New York with all these changes, generally the audience reaction felt so electric and energized and positive that — you never really know, but it felt like we were on our way to having a hit.

“Aida” received five Tony Award nominations — Best Lighting Design, Best Costume Design, Best Scenic Design, Best Actress in a Musical, and Best Original Musical Score — but not a nod for Best Musical, in a shock to the cast and production team.

Headley: I don't know what happened there.

Pascal: What justification could anybody possibly have on that nominating committee?

Scott: I felt badly because I knew they wanted more numbers or nominations or something that I couldn't deliver. I felt badly that I could have done more for them.

Williams: We knew that audiences loved it, they connected with it, they got it. And what you ultimately need for a show to run is audiences to love your show and audiences to feel the love that you were passing beyond the footlights. They were receiving it and they were giving it back. And then we had Heather Headley, who was just lighting the stage on fire every night.

Scott: For me personally, I knew Heather was a shining, shining star, a once-in-a-lifetime kind of performer. I knew that Adam wasn't ever appreciated in the way that he should be appreciated.

Pascal: I remember sitting there waiting with my heart beating, my heart out of my chest, waiting to see if I got a Tony nomination. And when I didn't, I was crushed.

Schumacher: That's why Elton and Tim didn't come. It was in protest.

Rice: I didn't even go to the ceremony.

Pascal: I'm not even saying we should have won. I'm just saying that by all accounts, there is no rational argument or explanation for how we didn't get a best musical nomination, given the circumstances.

Headley: I think there was a concern. I think if they had picked us, we would have won it, and then Disney would be the king of Broadway for a little bit.

Pascal: I'm furious about this to this day because how could that happen?

Schumacher: If you were nominated in every category, and then you're going to win, you know, Best Actress, best set, lighting — you're gonna win all these awards and [best] score. But you don't get nominated as a musical. What shenanigans were going on there?

Williams: We won a lot of Tonys, but we weren't nominated for Best Musical that year, which was heartbreaking for us, especially compared to shows that I still believe in my heart weren’t actually musicals. So, it was really a testament to our meeting the moment and the people — and people saying, “This is what we want to see in this moment.”

Headley: I'm grateful for my nomination. I'm grateful for my win. I'm grateful for what we had. But I don't know.

Schumacher: It would have meant [Disney] winning two years in a row, which probably also drove that, “We can't let Disney do that.”

Headley: I think my Tony's speech, when I gave it, really was that kind of like, look, this is ours. I felt like my Tony was the Best Musical Tony.

Rice: I was on holiday and I remember — this is again pre-mobiles — ringing up my office and talking about important things like mowing the lawn and how's the dog and all that sort of thing. Then at the end I said to my secretary, “I'm glad to see the house is still standing,” and she said, “Oh by the way, you won a Tony.”

Headley: I think it was a tough one for people to swallow, but in the end, you know how you kind of go, I lost that little battle but I won the war? Because I really do think the show proved itself.

Rice: God blimey, I had no idea. It was extraordinary, and Elton I don't think knew about it either. Neither of us turned up — and we were criticized for this.

Pascal: It was a really f***ed up year.

Headley: But again, you never know what nominating committees are looking for.

Rice: I thought, well, sometimes the Tonys think they're more important than the shows. I'd never been obsessed with Tony's and so it didn't cross my mind to go, but we probably should have gone. But we weren't trying to be rude. We just thought, well, they don't like us, so why should we go?

Headley: Last thing I'll say about that — it wasn't something that stopped us. There are other shows that don't get that nomination or don't get that win and the show doesn't do as well. We know this very well. But we didn’t — the show didn't have that.

%20Heather%20Headley%20and%20the%20Ensemble%20in%20Elton%20John%20%26%20Tim%20Rice's%20AIDA_%20Photo%20by%20Joan%20Marcus.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

Williams: I think the thing that allowed the show to go beyond the 5 minute review cycle was the fact that people would walk out of that theater and tell their friends how much they loved it. And then, you know, 4.5 years later, we actually lasted longer than every other show that was nominated for Best Musical.

“Aida” won four of the five Tonys it was nominated for and continued its run for years, with the cast growing closer as they continued their eight-show weeks. Scott left the show February 25, 2001. Headley departed September 9, 2001. The show returned post-September 11 and continued its run, with Pascal remaining until June 15, 2003 and Williams through the entirety of the production’s Broadway mounting.

Headley: We kept rolling for, I think it was 5 years, 3 or 4 years, they it kept going.

Williams: You know, “Aida” had an alley. And in the summertime we’d do barbecues between shows.

Headley: I am a child of Disney, and at the time, you don't understand that because “The Lion King” is still running. So in my puny head, I'm just like, of course, shows keep running. But now that I am older and, and into the business, you understand that having a 5-year run is a huge deal, having a 2-year run, a 1-year run is big.

Williams: In the old Palace, there was this big giant green room, and all of the crew rooms, the wardrobe room, the hair room, the actual crew room all fed into this big giant dressing room area. And all of the dressing rooms, save for a couple of the principal dressing rooms were upstairs. All of the ensemble dressing rooms were downstairs and the Aida star dressing room’s downstairs, and we would gather in that green room.

Schumacher: Adam put a fart machine under Sherie’s chair for her final performance. It has like 10 different fart sounds. And he put it under her chair for the scene where Aida is combing her hair. And I was offstage.

Headley: I carried it on my shoulders because all of a sudden these are people that you care about, and you also care about them in their livelihoods. That's how I felt about going to work every night being there, that the jobs were kept.

Williams: I mean, we celebrated everyone's birthday, everybody's baby shower, everybody's like any event, whether it was cast or crew, we were all together. And so we were close because we also had a place to gather.

Schumacher: Adam, at one point, his shirt wore out. And for Barbara Matera's shop to build a Bob Crowley shirt was like $1500. They built another one for him, and Adam didn't like it, so he went to the Gap and bought one and had it on for weeks before anyone noticed.

Headley: The jobs on stage, the jobs offstage, the crew and everybody like that. I'm always grateful that they had jobs for, you know, the 4 or 5 years that they did.

Schumacher: That show was full of those crazy things — the beautiful people who came in to replace, you know, that's the thing that people forget.

Williams: There were so many opportunities for us to be close and we took advantage of that. We really loved each other.

Scott: There's so many people in that cast that I love and I may never see again. It's so heartbreaking about theater. I hate that about it, but I also love that the more we create, the more of all of those people are in us and in everything we create. When I'm going on stage, all those experiences with Adam and Heather and all those people — I'm getting emotional — will be with me forever for the rest of my life. So I know they feel the same because I know that was a show about true love and we truly loved each other.

“Aida” played its final performance on September 5, 2004. Productions have since been mounted around the world, most recently in China and the Netherlands. Twenty-five years after it opened on Broadway, it remains a beloved part of the musical theater canon, with fans continuously clamoring for a revival.

Headley: The legacy of “Aida” sits with me — and I'll try not to get teary — it sits with me in my life. She came into my life on so many different levels.

Williams: I had such an extraordinary experience and that was my swan song as a performer. It changed my life, you know.

Pascal: I think its legacy is that it was a surprising underdog, given its circumstances. And I think it succeeded in spite of everything it had against it.

Hwang: We to this day remain the only Disney Broadway musical which is not based on other IP, Disney movies, or animated movies.

Schumacher: It's an honor to have done it.

Rice: It’s never come to England, that's the weird thing.

Williams: Tim and I have become fast friends because of the revival. He will tell you that “Aida” was his mother's favorite show. It was so incredible just to sit down with him and talk about the history of the piece and why it mattered so much to him and the way he got inside some of these songs and, and the beautiful poetry of these lyrics, how he and Elton worked together. We're still pen pals, Tim and I.

Scott: I never grew up with musical theater in my home or seeing shows. It wasn't a family thing at all, any kind of art or stuff like that. So I don't have that sentimentality about it, which I think is important that we have people come into the musical theater world that have no nostalgia about it, so that we can create new stuff that feels right, can take it forward.

Hwang: It showed that you can make a musical which is kind of YA-to-adult focused, at a time when there weren't that many of those, and that the musical could handle serious ideas and real issues and not have to be dependent on gags. And still become successful, reach an audience, move what we would now call a four-quadrant audience, and become a hit.

Scott: But I thought “Aida” did that in a way, taking things forward and with Elton and Tim, and again, Wayne and Bob.

Headley: At the time that “Aida” comes into my life, I am dating no one.

Williams: I'm always so surprised when I'll go into something and someone will say, “You were Nehebka!” It makes me giggle every time.

Headley: Halfway through I started dating my husband and I do believe that she was a preparation for that — we are in an interracial relationship — and she made me look outside of everything. She made me want that kind of love that you want to die for.

Williams: I love that my daughters did a musical theater class last year and their performance number they did was “Strongest Suit.” Listening to them rehearse to the cast album and being like, “Oh my God, they're singing my part!” is super weird and also amazing — amazing that they have that, that they love it. That it feels as relevant to them as it did to us 25 years ago. There were the shows that I grew up with, and now this is one of the shows that they grow up with.

Headley: I loved singing with Adam Pascal. I loved singing even on days when we were like, “I can't take you anymore.” I enjoyed it on days that you're not feeling well, you know you can go out there and Adam's gonna sing for blood and you're gonna be OK.

Scott: No one sings like Adam. Both Heather and Adam can cry tears and still sing like opera singers. It's crazy. I just was in awe of them.

Rice: I think somebody, somebody must have — I mean, we thought about it coming to London at the time, but we couldn't find the right theater and to be honest, I can't remember.

Pascal: I do think that a revival is definitely a long time coming, and I think it's a great time to do it.

Hwang: You've talked to Schele, so you know we have been working to try to make that happen.

Rice: And why not start it in London?

Hwang: Up to then I'd always been a playwright, only a playwright, and I sat in that room and listened to the music and watched the dance and just thought, “This is so much more fun than just listening to my own words.”

Rice: I mean, a lot of my English friends don't know it, or at least haven't heard it, but the ones who have or seen it or heard the album, they keep saying, “Oh, you must get that one back, it's so good.”

Pascal: Everyone loves the cast album. People just love it and I'm so grateful to have been a part of it. So I think that's its legacy. It’s a collection of music that people are still listening to.

Headley: I think for me that's the legacy of it, just this really amazing blessing and adventure that happened in my life that I didn't have any part in. Like it was just dropped on me. Needless to say, Disney could have picked anybody they wanted, and they were looking at many people, right? And I'm so grateful that they thought I could do it.

Rice: I wondered, well, maybe “Aida” is considered woke, but then I thought, hang on, it's a story about how wrong slavery is. If you can't say that in theater, what can you say?

Headley: I carry her with me to this day, and also I carry her with me because I've always said this: it was the best of times and it was the best of times. Even those times that I was on the stage bleeding, I had to be carried off in a stretcher. The times I was home going, “I don't know if I can sing tonight,” the days that I didn't speak because I had to sing — wouldn't trade it for the world. Needless to say everything that came from her, from playing her, the hardware that comes from it — I'm incredibly grateful.

Videos