Review: MACBETH, starring Sam Heughan and Lia Williams

Director Daniel Raggett follows his uber-successful Edward II with an explosive Macbeth.

![]() Something wicked this way comes: it’s another exciting high-concept Shakespeare. Director Daniel Raggett moves the action of the Scottish Play to a safe-house pub in the midst of a racketeering war. Succession meets Sons of Anarchy with a hint of The Sopranos in this daring, new production. With a hypnotic tempo that’s almost cinematic in nature, Raggett leaves you on the edge of your seat, gasping for air, mouth gaping and eyes wide. It’s Macbeth like you’ve never seen it before. Is it an extravagant idea on paper? It sure is. Does it work? Flawlessly so.

Something wicked this way comes: it’s another exciting high-concept Shakespeare. Director Daniel Raggett moves the action of the Scottish Play to a safe-house pub in the midst of a racketeering war. Succession meets Sons of Anarchy with a hint of The Sopranos in this daring, new production. With a hypnotic tempo that’s almost cinematic in nature, Raggett leaves you on the edge of your seat, gasping for air, mouth gaping and eyes wide. It’s Macbeth like you’ve never seen it before. Is it an extravagant idea on paper? It sure is. Does it work? Flawlessly so.

By reducing the scope and bending the narrative into a battle for the control of an underground ring of some sort, the direction amplifies the magnitude of the story. The play goes from being an abstract notion to becoming a very real tale of sheer dynastic survival. In the best and most complimentary way possible, it’s bloody, coarse, and dirty.

The atmosphere is immediately spotless, with details of exquisite immersive nuance. The carpet of the auditorium flows onto the central stage, adding a voyeuristic element to the staging. The intimacy of The Other Place is crucial to the end result. Anna Reid designs a dusty old-man boozer stuck in the 70s, traditional and with a reputation to maintain.

Shakespeare’s language deliciously adapts to the free house framework: the phone rings twice and Macbeth remarks that “the bell invites [him],” his wife throws Banquo a disposable lighter when he asks for “a light,” and switchblades replace swords. The hand-kissing and royal references mould well to the mob-like venture too, so the script can retain its original beauty and rhythm without stretching too much.

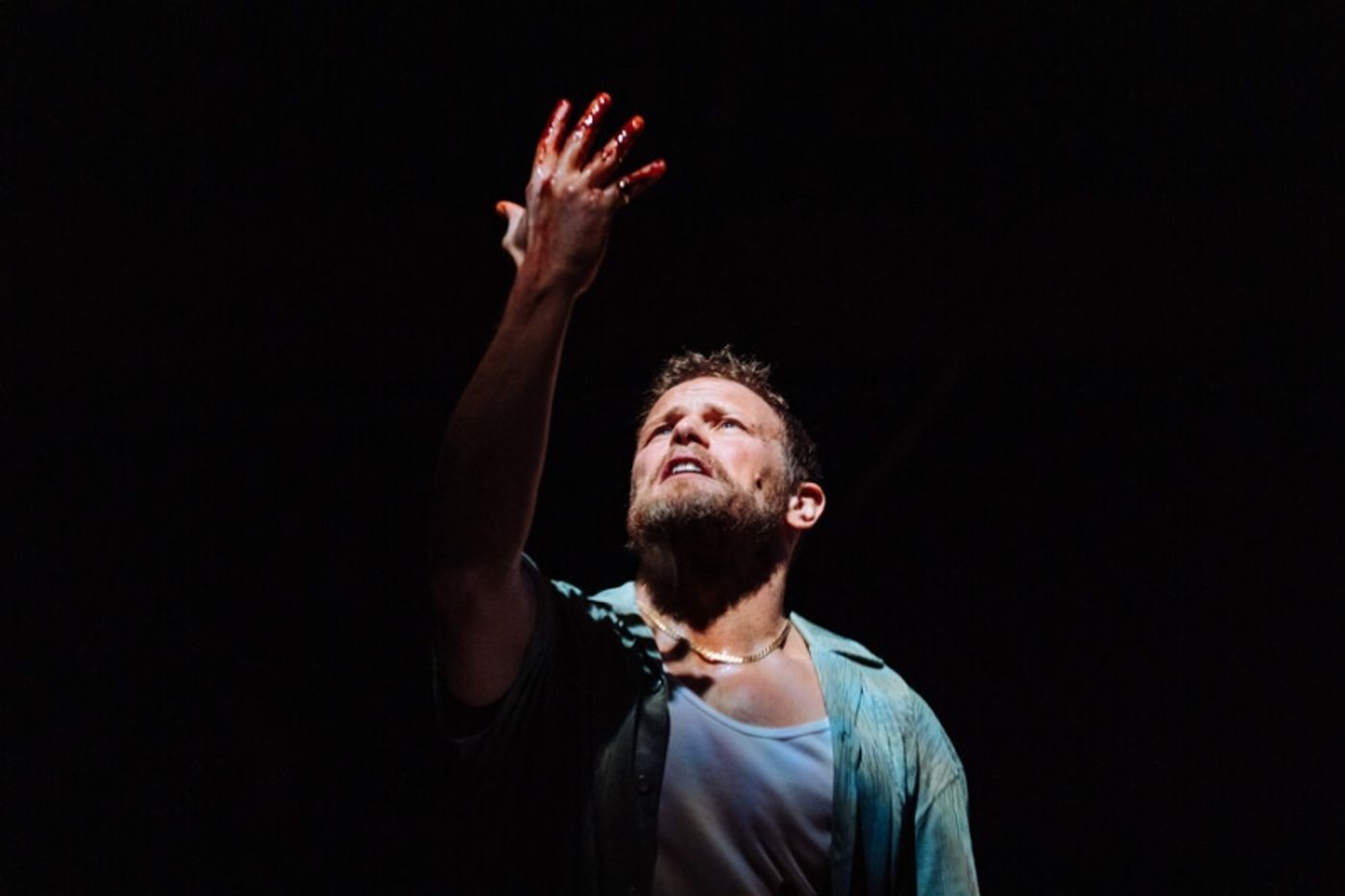

Sam Heughan is a Glaswegian gangster, the newly anointed Thane of Cawdor, and (one assumes) the owner of the establishment. Lia Williams is his ambitious wife, (Land)Lady Macbeth. Though their roles are conventional, their dynamic feels novel. It might be uncouth to point out, but the fact that Williams is a decade and a half older than Heughan is enough to add depth to their relationship. Where Heughan’s Macbeth isn’t prompt at scheming, she sees their future unfold ahead of them like a red carpet.

But Heughan starts off pensive, moderate in his reactions as a consequence of the prophecy he stumbled into earlier that night. He recognises the weight of the role, how onerous and dangerous it is, and is weary. Williams, however, has a different approach. She initially hides her frustration about his reticence, then shows herself quietly dismayed when he flips. They plot and scheme, very touchy throughout, and tremendously sexy.

His journey to vanity is measured: once he’s done the deed, he freaks out in a very quiet, methodical manner, soothed by his wife. He is worried, not cocky (heavy is the head and all that), until Banquo starts haunting him and paranoia suddenly courses through him. That’s when Heughan is at his best, in his erratic and alarmed form.

In a chilling moment involving Macduff’s child, Williams realises that her husband has lost it entirely. We have proof of this in a disturbingly tender scene where he slow-dances with a corpse, intoning a singsong “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” speech. They do truly great work together.

Raggett’s vision doesn’t shy away from cruelty, nor does he skimp on fake blood. He curates the tension exquisitely, raising it steadily and letting the audience savour its feeling. Sound designer Tingying Dong layers the soundscape with a nearly undetectable, yet ever-present and lingering track that expands until Raggett breaks the climax with clockwork timing.

This Macbeth has the spook factor too. It leans into folklore and paganism by way of having the Three Sisters perform a séance in lieu of having to include Hecate – a very wise choice that keeps it grounded. Eilidh Fisher, Irene Macdougall, and Alison Peebles are utterly creepy as the witchy presences. Steeped in symbolism, they’re intimidating not because of their weirdness, but because of their restraint.

Appearing as three generations of women, they’re timeless figures, ancient, and eternal. Macbeth can’t help but stare at them, charmed and apprehensive at their revelations. The whole “not of woman born” debacle doesn’t seem to lull him into safety; it nestles into him and taunts him. The mob setting is the gift that keeps on giving, as suspicion finally blooms once Duncan (Gilly Gilchrist, who sports half a Glasgow smile like a badge of honour) is killed.

Alec Newman’s Macduff instantly but discreetly locks in on Macbeth. Brazen and proud at the start, he receives the report of his family’s brutal slaughter with silent horror, briefly crying out a wail at the news. His resolve turns fiery and precise. When he and Heughan are alone, it is easy to see that, in other prophecy-less circumstances, Macduff would have probably capitulated against Macbeth due to the difference in their physical builds. It adds a riveting detail to Macbeth’s final reckoning.

Other highlights in a cohesive company are Nicholas Karimi as a gentle, funny, ultimately unearthly Banquo, and Jamie Marie Leary as Lady Macduff, who makes us care about her character with one single affecting sentence. The cast work in unison, lifting each other up to deliver a most creative adaptation. It’s unsettling and disquieting, profound and engaging. Bold in what it’s trying to do, it definitely won’t please the purists.

Macbeth runs at The Other Place in Stratford-upon-Avon until 6 December.

Photo Credits: Helen Murray

Reader Reviews

Videos