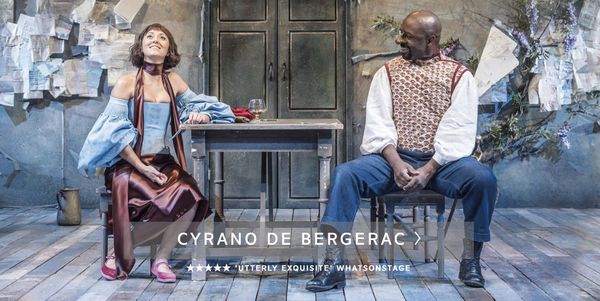

Review: CYRANO DE BERGERAC starring Adrian Lester, RSC Swan Theatre

New adaptation can't quite wriggle free of its heritage

Taking on Edmond Rostand’s celebrated tale of the tragic hero who can encompass the whole world as a poet, yet not see beyond the end of his nose as a lover, is quite the challenge. It’s very French, and it has been adapted on film as a smash hit Hollywood comedy with Steve Martin at his best and as a Cannes Film Festival award winner, with Gérard Depardieu giving an all-time high performance.

Taking on Edmond Rostand’s celebrated tale of the tragic hero who can encompass the whole world as a poet, yet not see beyond the end of his nose as a lover, is quite the challenge. It’s very French, and it has been adapted on film as a smash hit Hollywood comedy with Steve Martin at his best and as a Cannes Film Festival award winner, with Gérard Depardieu giving an all-time high performance.

But Cyrano is not as established a presence in this country as, say, Hamlet or Sherlock Holmes, so the challenge for adaptors, Simon Evans (who also directs) and Debris Stevenson, is to say something that will build on the knowledge of those familiar with him and also introduce his singular personality to those who are not.

Meeting that need leads to some slightly clumsy hallucinations on Cyrano’s part, a framing device that ebbs early momentum and a run time above three hours. Fortunately they have an actor in Adrian Lester who can meet those considerable demands, an astonishingly physical presence at 57, every inch the old fighting man whose sword was his fortune if not his passion.

He lives for words - how they illuminate the world, how they provoke laughter and tears, how they can take a man down more comprehensively than a duelling foil. And he also lives for Roxane, his childhood friend (a bit of a stretch, that, to avoid source material’s considerable age difference that would raise eyebrows these days). She’s recently widowed and possessed of a spirit and intellect to near match his own - not many women like that in 17th century France. But the wordsmith cannot craft the phrases to tell her of his love, his nose too long, his confidence too short. Rejection too traumatic to contemplate, because he cannot trust her, he tricks her.

His vehicle is Christian, a young recruit in the Reserve who has caught Roxane’s eye and he hers. Handsome and foolishly brave, the lad would be a catch for a frivolous young mademoiselle of Montmartre, but the lad is a country boy, tongue-tied and uncultured, as rough as the earth in which he farms.

Cyrano realises that he can make Roxane happy by giving her what she wants - Christian’s looks and Cyrano’s language. He writes letters, purportedly from the younger man, woos her unseen from a window in a cod Brummie accent and protects the untrained soldier in battle, insofar as he can. Their love thrives, Cyrano has his compensation and the deception holds - until it doesn’t.

In the smaller of the RSC’s theatre spaces, the fighting is both intimate and epic - clashing metal and big explosions and scary blackouts. That contrasts with the calm that allows the poetry to seep into our hearts as much as it does into Roxane’s. We see the trick, something we would not countenance it in our own lives, indeed it’s probably illegal in an age of online scammers - it makes us uneasy. But in 1640s Paris, with death from war, disease and famine never far away, the deception, or rather its raising of the spirits of three people hanging on by their fingertips to the joys it brings, feels excused, even welcomed.

It helps that the cast is so warm in their playing that we very much like the men and women whom we meet. Susannah Fielding gives Roxane plenty of spark and courage, so it’s all too easy to see Cyrano’s infatuation in this most modern of women. She plays beautifully off Greer Dale-Foulkes’s Abigail, her servant whose flightiness is as much enjoyed by Roxane as it is by her, a fine comic double act that rolls through the play.

Amongst the support, Scott Handy goes from all but twirling his moustache as the villainous Comte de Giuche, a cowardly seducer, as the horrors of war, and his witnessing of the price paid by brave men and boys, transforms his narcissism into, if not quite heroism, then quiet introspection. Philip Cumbus is also super as Cyrano’s officer and friend, Le Bret, a warrior who wears his bravery lightly and is loyal to the end.

And Lester? He has the necessary charisma and the swaggering bravado that collapses instantly in the presence of Roxane, but he plays the role suffused with anger at himself and the second-raters (like Guiche) with whom he must work. That direction limits the key element of Cyrano’s response to the world - an all but universal disdain. In turn, that limits the melancholy that must always be clinging to him, the loneliness to which he has condemned himself, the sheer size of the Roxane-shaped hole in his heart. Of course, I may just be asking for a Depardieu redux, but that’s the problem an iconic performance gives to those who take on a new approach to a masterpiece of storytelling.

Such quibbles aside, this is an exhilarating show, a rollercoaster action-romance with wit to burn and a poignancy to shatter the hardest of hearts. Cyrano may have been a fool in the one thing that matters most in his life, a man who sacrificed truth only there, a flawed hero as so many are, but you understand him and, probably, like Roxane, forgive him too.

Cyrano De Bergerac at the RSC Swan Theatre until 15 November

Photo image: Marc Brenner