Interview: Gregg T. Daniel on JOE TURNER'S COME AND GONE at A Noise Within

Opens October 18 through November 9

Set in a Pittsburgh boarding house in 1911 during the Great Migration, August Wilson’s Joe Turner’s Come and Gone introduces us to a group of men and women teetering on the brink as they search for lost family, identity, and purpose in the aftermath of slavery. The play’s title is a line from an early blues song, “Joe Turner’s Blues,” about the post-Civil war convict leasing system, a form of neo-slavery that sentenced Black males who ran afoul of the law to seven years of hard labor on chain gangs, profiting from their labors.

I decided to speak with the play’s director Gregg T. Daniel (pictured, courtesy of A Noise Within) about his production opening October 18 at A Noise Within in Pasadena.

Thanks for taking the time to speak with me today, Gregg. First, tell me about your theatrical training and experience directing plays in Los Angeles.

I was born and raised in New York, which was the theater capital of the world at the time. There were so many plays, on Broadway, Off-Broadway, Off-Off-Broadway; every kind of theater was available to a kid who was in love with it. That passion served me well at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. The Shakespeare Festival Public Theater was around the corner, and the Negro Ensemble Company was just a few blocks away. We had seminal theater groups like the Wooster Group, La MaMa, and Ontological-Hysteric Theater, groundbreaking theater troupes. I was fortunate to have all of that around me so early on.

In Los Angeles, I trained as an actor first and eventually segued into directing (although I still act). I’ve directed at some of the best theater companies across LA: the Mark Taper Forum, Pasadena Playhouse, A Noise Within, the Odyssey Theatre, Rogue Machine. I’ve been lucky to freelance widely and have truly enjoyed it. I also founded my own company, Lower Depth Theatre, in 2010. I studied New Media at UCLA and participated in the Directors Lab at Lincoln Center too.

I’ve been exposed to a lot of theater but really, there’s nothing like the experience of making theater. Especially after the pandemic, when everything was shut down, even Broadway. That left a real void. It’s been meaningful to see companies come back and audiences return. And now I’m about to open Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, which is our sixth August Wilson play in the 10-play cycle.

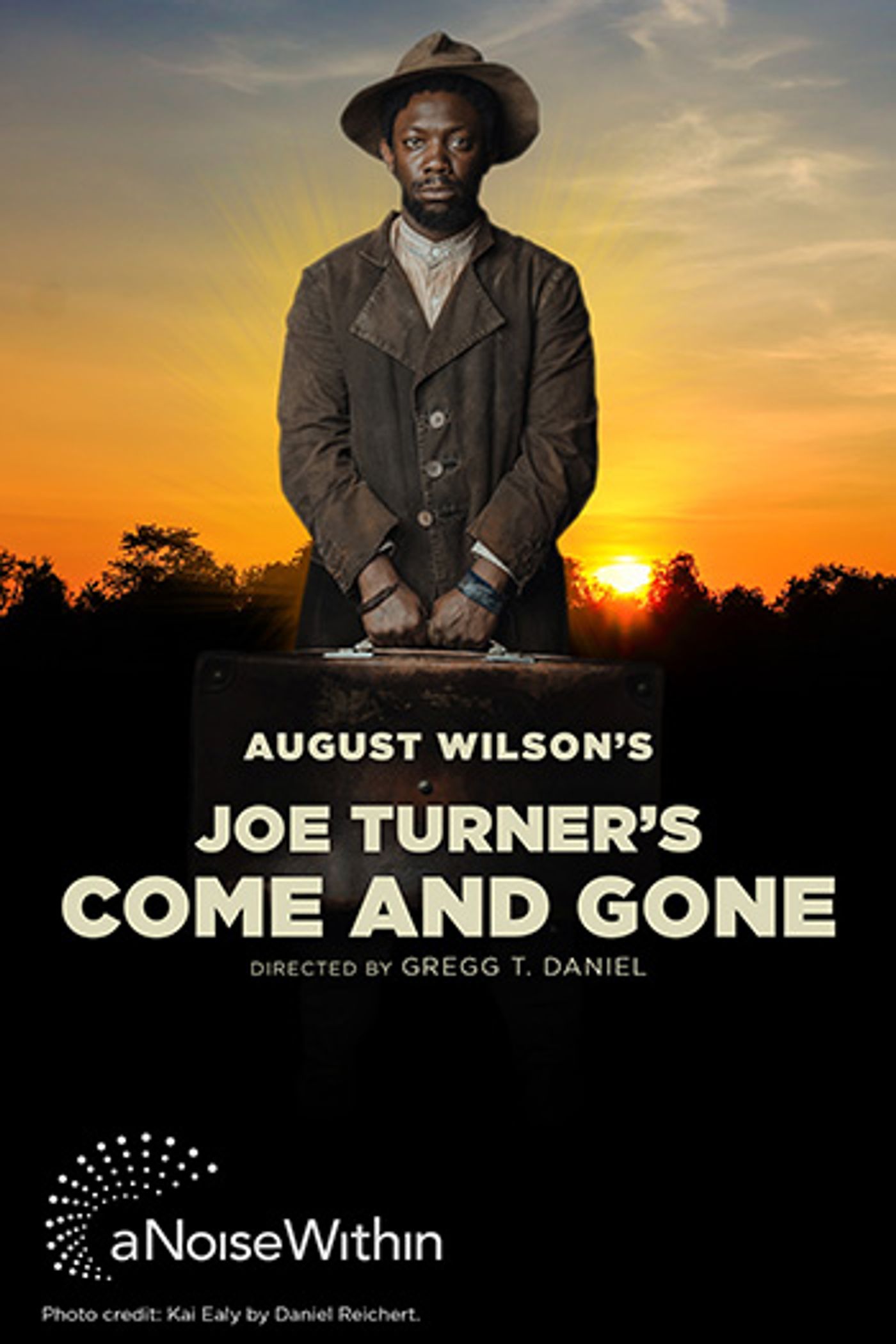

Kai A. Ealy in Joe Turner's Come and Gone

All photos credit: Daniel Reichert

This is the sixth August Wilson play A Noise Within has staged as part of its commitment to the American Century Cycle. How does Joe Turner’s Come and Gone, the second in the cycle chronologically, fit into that larger journey?

Wilson had an audacious goal, to write a play for each decade of the 20th century chronicling African American life. This play focuses on the Great Migration, when Black Americans moved en masse from the South to Northern cities in search of better jobs and safer lives. The South in 1911 was a violent and oppressive place, so people moved North really seeking freedom. Looking for a way of life where they could be safe, raise their children, own property, and find more opportunity. It’s a uniquely American story – people pursuing a dream. And this migration happened just 46 years after slavery was abolished, so many were still directly impacted by it. Joe Turner’s Come and Gone is about individuals trying to figure out who they are in a post-slavery America, within themselves and in community. It’s a beautiful chapter in the tapestry of American history.

What makes Joe Turner’s Come and Gone particularly resonant in 2025, nearly 40 years after its premiere?

Because in many ways, we’re still fighting for full enfranchisement in American society. It feels as if African American history is being erased or rewritten. Monuments to our history are being taken down, our contributions minimized or challenged. So this play feels especially timely. It reminds us that African Americans are integral to the American story. Wilson’s work becomes even more poignant when we’re faced with attempts to marginalize or erase that history.

The play takes place during the Great Migration, in a boarding house that becomes a crossroads for souls in search of identity. How do you bring that sense of searching and belonging to life on stage?

I’m fortunate to have a talented cast and design team. Remember, these characters are looking for connection and belonging. One of the key spaces in the play is the kitchen. August Wilson set many scenes there, which makes sense; food and shared meals bring people together. Food is a great unifier. The kitchen becomes a space of connection, healing, and even conflict. Our brilliant set designer, Tesshi Nakagawa—who I worked with earlier this year on Topdog/Underdog and the Pulitzer Prize-winning play The Piano Lesson—has created an amazing set.

Tell me about the characters and the actors portraying them.

There are 11 characters, two of whom are children. Interestingly, this play features more women than any other of Wilson’s plays—four women and five men. It’s a multi-generational story. You have the older generation, like Bynum. He is the griot, the seer, the visionary. On the other end, you have the younger generation who’ve just arrived from the South, like Jeremy, who’s been in town for two weeks and is still wearing his rural shoes. Then there’s women in search of companionship and partnership. Mattie Campbell is looking for the man who left her. Molly Cunningham lives by her beauty and uses it to gain agency.

Then you have Seth and Bertha, who run the boarding house. An interesting thing about Seth is that he was born a freedman, and raised in the north. Herald Loomis is a major character. He was enslaved for 7 years by Joe Turner. Herald is now searching across the country for his wife with his daughter, in hopes of all three being reunited.

Each character is searching for something, belonging, family, meaning, peace, identity. The boarding house becomes this temporary container where they clash, connect, and evolve.

Have you directed any of them previously? If so, where and when?

Yes, at least half our cast now have been in other August Wilson plays at A Noise Within. What’s wonderful about that is that audiences recognize them, and love it! Veralyn Jones, who plays Bertha, Alex Morris as Seth, Kai A. Ealy and Nija Okoro, who were both in The Piano Lesson. Some of these actors I’ve worked with outside of A Noise Within, too. When we did Gem of the Ocean, there was no plan to complete the full cycle. But over time, we saw the enthusiasm build. Donors and audiences supported the vision, and now we’re on our sixth play.

With such a rich ensemble of characters, how do you help each actor find depth while keeping the story’s rhythm and community feel intact?

That’s the core challenge of directing. Every actor works differently. Some are very fast with their vision, others take more time to absorb and build their performance. Patience is important, but also paying attention. They’re all committed and ambitious, it’s just about zeroing in and understanding what they need from me and how I can help. Is it verbal? Is it visual? At the same time, I’m shaping an ensemble. How I blend each actor’s needs into an ensemble is really the excitement also of directing.

These actors are incredibly talented. They bring a lot of skill. They teach me a lot. I’d done extensive research before I saw the play. I read the books, the reviews, but once the actors start saying the lines, there’s a whole new level of learning for me. They’re teaching me about the characters in their artistry. So it’s a mutual process.

The idea of “finding your song” is central to Herald Loomis’ journey. What does that metaphor mean to you, and how do you hope audiences will connect with it?

To me, the metaphor is about identity. Who are we as individuals? As a community? As a nation? America is unique in that it was built on immigration and displacement, people coming here seeking freedom, safety, and opportunity. Everyone, in some way, is looking for belonging. That’s what makes Wilson’s work so powerful. It speaks to a universal human need, to feel safe, to contribute, to connect, to want a better life. Audiences see their own unique family struggles in these stories, even if the cultural specifics differ.

Christianity and African mysticism weave throughout the play. How are you approaching the balance of those spiritual forces in your production?

In many ways they clash but in many ways they also complement each other. For example, Bertha goes to church regularly, but she also sprinkles salt at the doorway and lays down pennies, rituals rooted in spiritual practices. They coexist.

It’s not just about religion, it’s about ritual. We all have rituals that make us feel connected. Wilson integrates these into the fabric of the play to reflect how people held on to both faith and heritage.

Wilson wrote about deeply African American experiences but also universal human questions. What do you hope audiences of all backgrounds carry with them after seeing Joe Turner’s Come and Gone?

I would be very honored and complimented if they thought about the meaning of family. Not just the traditional biological family or even extended family, but our chosen family too. Friends who become brothers and sisters and other individuals we embrace as such. I’d love for audiences to think about who they consider family, why they love those people, and how those connections form a community. It’s important, it takes us back to who we are as people.

Anything else you would like to share about yourself and/or the play?

I’m honored that it seems I’m on track to direct all ten plays in August Wilson’s cycle. I’m thrilled we can bring his work to the people of Los Angeles. For a West Coast theater the size of A Noise Within to take on such an ambitious project, it’s truly remarkable! Each time we mount a play, the audience grows. People are excited to see what comes next.

Thanks so much!

Thank you. Shari

Joe Turner’s Come and Gone performances run October 18 through November 9 on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays 7:30 p.m., with 2 p.m. matinees every Saturday and Sunday (no matinee on Saturday, Oct. 19). Four preview performances take place at 2 p.m. on Sunday, Oct. 12, and at 7:30 p.m. on Wednesday, Oct. 15; Thursday, Oct. 16; and Friday, Oct. 17. Student matinees are scheduled on select weekdays at 10:30 a.m.; interested educators should email education@anoisewithin.org.

Tickets to Joe Turner’s Come and Gone at A Noise Within, 3352 E Foothill Blvd. in Pasadena 91107 start at $51.50 (including fees). Student tickets start at $20. Tickets to the previews on Wednesday, Oct. 15 and Thursday, Oct. 16 will be Pay What You Choose starting at $10 (available online beginning at noon the Monday prior, and at the box office beginning at 2 p.m. on the day of the performance). Discounts are available for groups of 10 or more. For more information and to purchase tickets, call (626) 356–3100 or go to www.anoisewithin.org.

Special events during the run include post–performance conversations with the artists every Friday (except the preview) and on Sunday, Oct. 26. GalaPro closed captioning is available at select performances, courtesy of the Perenchio Foundation. A one-hour INsiders Discussion Group will take place prior to the matinee on Sunday, Oct. 19 beginning at 12:30 p.m.

Saturday, Oct. 25 at 7:30 p.m. is “Black Out Night,” an opportunity for an audience self-identifying as Black to experience the performance together. Tickets include a post-show reception (non-Black-identifying patrons are welcome to attend, or to select a different performance).

Videos