Review: LA CAGE AUX FOLLES at Théâtre De Châtelet

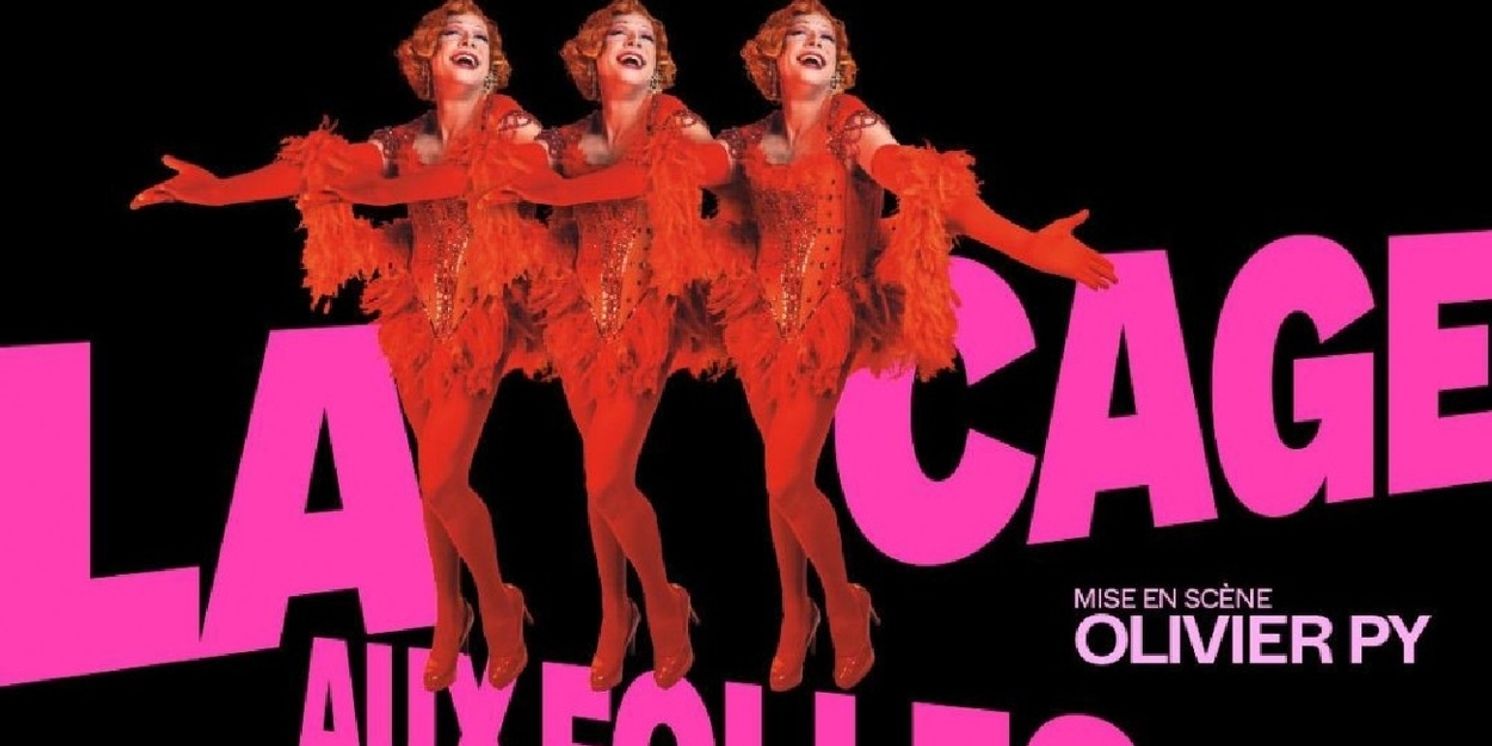

At the Théâtre du Châtelet, Olivier Py and Laurent Lafitte bring Jerry Herman’s musical back to France in a lavish, thought-provoking revival

French audiences have tended to resist Broadway adaptations of their own theatrical treasures—with the notable exception of An American in Paris, which enjoyed a triumphant debut at the Théâtre du Châtelet in 2019—while shows such as Gigi and Can-Can still seem unlikely ever to grace Paris stages; a previous French version of La Cage aux Folles itself fell flat, as local crowds struggled to connect with Jerry Herman's vibrant melodies and preferred the familiar face of Michel Serrault in the role of Albin. Now, however, thanks to Châtelet, the musical has finally come home with a fresh French-language production (December 5 2025 - January 10 2026), marking the first significant revival of its kind in France for many years—coming just a year after the same venue successfully revived Les Misérables, offering a glimmer of hope that delayed appreciation for Broadway reinterpretations of French works is still possible.

Olivier Py's direction reimagines Jean Poiret's classic story of romance, self-discovery, and pretense as a dazzling cabaret extravaganza that balances enduring appeal with modern relevance, centering on Georges, the polished manager of a Saint-Tropez drag venue, and his exuberant partner Albin—the glamorous Zaza—whose stable life begins to unravel when their son announces his intention to marry the daughter of a right-wing politician (in America, an obvious Republican—in France, a not so subtle Lepeniste or Zemmouriste). The result is a witty farce of disguises and misunderstandings, animated by Herman's powerful songs, notably "A Little More Mascara" and "I Am What I Am," which affirm authenticity in the face of conformity; Py's new French text shines with sharp humor, emotional depth, and clever dialogue in both lyrics and script, refreshing the language for contemporary audiences while reincorporating elements from Poiret's original play that were absent from the musical, including a memorable toast-related mishap and a comical plates scene that resonate with French connaissuers. Py's lyrics, however, occasionally feel less naturally aligned with Herman's melodies than in the late Alain Marcel's previous adaptation (1999).

The work's history underscores its remarkable cross-cultural versatility, beginning as Poiret's 1973 play—a lighthearted comedy partly inspired by Charles Dyer's Staircase, which addressed same-sex relationships with warmth and wit at a time when such narratives were rare—enjoying nearly 1,800 performances in Paris before inspiring a film trilogy launched by Édouard Molinaro's 1978 version starring Ugo Tognazzi and Michel Serrault, which earned a Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film. An American remake followed in 1996 with Mike Nichols's The Birdcage, starring Robin Williams and Nathan Lane and grossing more than $185 million worldwide, while the stage musical debuted on Broadway in 1983 with Harvey Fierstein's book and Jerry Herman's (1931–2019) score, securing six Tony Awards including Best Musical and running for 1,761 performances before acclaimed revivals in 2004 and 2010.

Groundbreaking on multiple fronts, the show revived the lavish style of the golden-age musical at a time when it had largely disappeared, positioning Herman alongside earlier triumphs such as Hello, Dolly! and Mame, standing in contrast to the more introspective works of contemporaries like Stephen Sondheim—whose Sunday in the Park with George famously lost the Best Musical Tony to La Cage. Above all, its central premise was daring in 1983: a devoted gay couple raising a child within the world of drag performance, a subject that prompted anxiety during Boston previews for Herman, Fierstein, and director Arthur Laurents, who feared audience resistance to a story with few Broadway precedents beyond hints in Cabaret, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, and openly gay supporting characters in Applause (1970) and Coco (1969). Those fears proved unfounded as the show demonstrated its universal resonance through Herman's deeply romantic score, particularly the tender ballads "With You on My Arm" and "Song on the Sand," which transcended any single demographic to speak to the fundamental human experience of love and partnership. The British response to the contoversial material was harsher, with some Torys advising the public not to see La Cage, as they might catch AIDS by just watching it, resulting in a much shorter run at the London Palladium, a poor choice of venue to begin with, as it has been traditionally associated with family entertainment.

This Châtelet revival, adapted and directed by Py, brings the musical back to its French origins while preserving its exuberant spirit, albeit with some trade-offs, as Py—one of the most influential figures in contemporary French theater and opera and former director of the Avignon Festival—delivers thoughtful, immersive staging rooted in the vibrant atmosphere of a Riviera nightclub. His interpretation carefully honors the material's emotional core while bringing contemporary sensitivity to questions of identity and self-expression, evident in choices that range from casting to staging.

Visually, the production proves a mixed but often sumptuous affair, with Pierre-André Weitz's designs—drawing on his extensive experience in opera and theater—creating a dynamic cabaret world through dozens of rapid scene changes that capture Saint-Tropez glamour via glowing bars, celestial backdrops, and fluid shifts between intimacy and spectacle. The overall look is richly indulgent, though Weitz's costumes vary in impact: Zaza dazzles in opulent gowns, plumes, and glitter, and the ensemble balances flamboyance with poignancy, while the Cagelles' initial outfits disappoint despite more than 150 costumes overall, including show-stopping red-and-gold ensembles for the star. Speaking of the Cagelles—an all-male ensemble, whereas the original mixed men and women—they unfortunately lack individuality, wearing all the same outfits, but yet, sometimes they aren't in perfect unison in the execution of the occasionally uneven choreagraphy by Ivo Bauchiero, who sadly decided to eliminate the Can-Can section from the title number. The clever use of gendarmes and gendarmettes, choreographed by the late Vivian van de Mael, in the 1999 production at Mogador was a better alternative!

Laurent Lafitte excels as Albin/Zaza, drawing on his distinguished stage and screen career to deliver a captivating, multifaceted performance that combines diva excess, heartfelt vulnerability, and pinpoint comedy, all animated by impeccable timing and expressive physicality. At 52, he radiates youthful vitality, conveying deep emotional wounds from familial tensions with little more than a glance, playfully engaging the audience through a recurring prop gag, and lending Herman's melodies a warm, resonant baritone.

Damien Bigourdan offers a steady and charming Georges, infusing the role with an operetta-inflected boulevard style that echoes Poiret's original play—whether by design or instinct—and complements Lafitte beautifully, their chemistry, especially in "Song on the Sand," feeling genuinely lived-in and deeply affecting.

The supporting cast shines throughout, with some performers leaning into exaggerated boulevard conventions—most notably Émeline Bayart as Madame Dindon, a choice that aligns well with French familiarity with Poiret's theatrical world—while Emeric Payet provides strong support as Jacob, Gilles Vajou and Lara Neumann impress markedly, and the ensemble contributes vibrant voices drawn from France's musical-theater scene.

In the pit, Christophe Grapperon conducts Herman's glorious score with the Orchestre des Frivolités Parisiennes, though the reduced nine-piece ensemble cannot fully replicate the richness of the original 22-player orchestration, resulting in thinner textures and a noticeable absence of string warmth.

Some challenges remain, as diction can blur against the band, Py's energetic text sometimes strains against Herman's melodies, and the venue's acoustics soften vocal impact in large ensemble moments—issues partially mitigated by the use of subtitles.

Still, this is a production too joyful and generous to overlook: despite its flaws, the Châtelet revival reconnects La Cage aux Folles to its French roots while engaging contemporary questions of identity and belonging, and through Lafitte's commanding performance and Py's ambitious, if imperfect, vision, offers something both profound and uplifting—leaving audiences bathed in glamour, light, and the enduring warmth of Jerry Herman's music.

Reader Reviews

Videos