Review: THE LADY FROM THE SEA, starring Alicia Vikander and Andrew Lincoln

A divisive adaptation cradles intriguing performances by world-famous names.

![]() In a nondescript little village somewhere in the Lakes, Ellida has settled into her routine. A novelist, she is the second wife of a good-natured country doctor who has a private practice at the end of his enormous garden. The safety of her newfound decisions shackle her. When she learns that a former boyfriend of hers, with whom she had an illicit romantic liaison in her youth, is out of prison, her world shakes. She made a promise to him; will he find her so that she can keep it? Shall she abandon the life she knows, with a husband who adores her, to pursue her old dreams? Shall she stay and mend her relationships? Does she have any other choice?

In a nondescript little village somewhere in the Lakes, Ellida has settled into her routine. A novelist, she is the second wife of a good-natured country doctor who has a private practice at the end of his enormous garden. The safety of her newfound decisions shackle her. When she learns that a former boyfriend of hers, with whom she had an illicit romantic liaison in her youth, is out of prison, her world shakes. She made a promise to him; will he find her so that she can keep it? Shall she abandon the life she knows, with a husband who adores her, to pursue her old dreams? Shall she stay and mend her relationships? Does she have any other choice?

With a cast as starry as the Ibsen’s Norwegian skies, The Lady from the Sea is adapted into a thrilling, biting comic drama by Simon Stone. It features the theatrical return of Andrew Lincoln alongside the stage debuts of Academy Award winner Alicia Vikander, Brutalist actor Joe Alwyn, and rising star Isobel Akuwudike. This is not the play for you if you’re looking for steady auroras and sad prose. Ibsen (Stone’s version) is surprisingly funny, but not thoroughly convincing.

The piece wants to do too much. It sits solidly between cringe and clever, but it’s not self-deprecating nor unabashed enough to embrace its quirky slant. It’s eager to please a younger audience by exuding exceedingly contemporary references, yet it also strives to gratify the traditional theatregoer by diving into longer dramatic sermons. At its best, it keeps the balance exquisitely. At its worst, it confuses trendy lingo with relevance in a lineup of overwrought arguments. Mostly, you can tell it was written by a man in his forties with a very upper-class take on eccentricity.

We are immediately introduced to Edward (Lincoln) and his Cornish cousin Heath (Alwyn): “Two very well educated Anglo-Saxon men,” according to the latter. The dialogue is immediately entertaining. They exchange rapid-fire pleasantries, circling the elephant in the room – is Heath dying? – by citing poetry. Edward fesses up to getting his quotes from Instagram, but it’s the set-up for Heath’s performative intellectualism and its echoes. The first act introduces each character and their trauma with a galloping script imbued with irony. Stiff characterisations border on caricatures, but they generate a great deal of accidental comedy. The only role that’s deliberately removed from any hint of levity is Ellida.

Vikander offers a solid performance. Though she often doesn’t project her voice, there’s gorgeous depth in her Ellida. She delivers affected monologues that dip into startled paranoia and defenceless emotion to create a woman who got swept up by life. It’s heartening to see Stone depart from the fate Ibsen prescribes, letting her break the cycle and choose her own healing over a man. The lack of communication and understanding that runs between her and Edward materialises in a singular shortage of chemistry between Vikander and Lincoln.

He tries to connect with Ellida, but the memory of his late wife pervades their marriage. Lincoln is an amiable, devoted doctor. His affection for Ellida is evident, but never explored with the aim of discerning whether he simply enjoys the idea of a young wife or there’s anything more to it. He never towers over her, always stooping down, almost submissive, to address her instead. Even in anger, he opts for removing himself rather than being cruel, controlling his explosions and categorically refusing to intimidate her. The show becomes a true thing of beauty when the actors get a chance to crack open their characters properly.

Once Stone starts to unpack the layers of dysfunctionality that build the family dynamic, each member of the company finally blooms in their craft. Gracie Oddie-James (Asa), Isobel Akuwudike (Hilda), and John Macmillan (Lyle) steal the scene. Their trio is a highlight, together and individually. The two sisters are captivating; they’re biting in their caustic quips, speaking fluent sarcasm and age-appropriate emotional intelligence (Asa is finishing her master’s and Hilda is 17). Macmillan presents Lyle as the most self-aware man that could ever exist in an Ibsen play.

He calls out Edward on his pseudo-sophistication and covert narcissism as well as Heath’s art bro tendencies with a list of equally pretentious intellectual dad jokes before he realises his position in the dramatic ecosystem. Alwyn excels when he reels it in. He declaims and overacts a bit, blowing up in convoluted ardour and occasionally bordering on the pathetic, but does incidental comedy very well. Last but not least, Brendan Cowell ambles between scary and sexy as the haggard ex-lover who delves into the governmental weaponisation of activism and the flaws of the justice system.

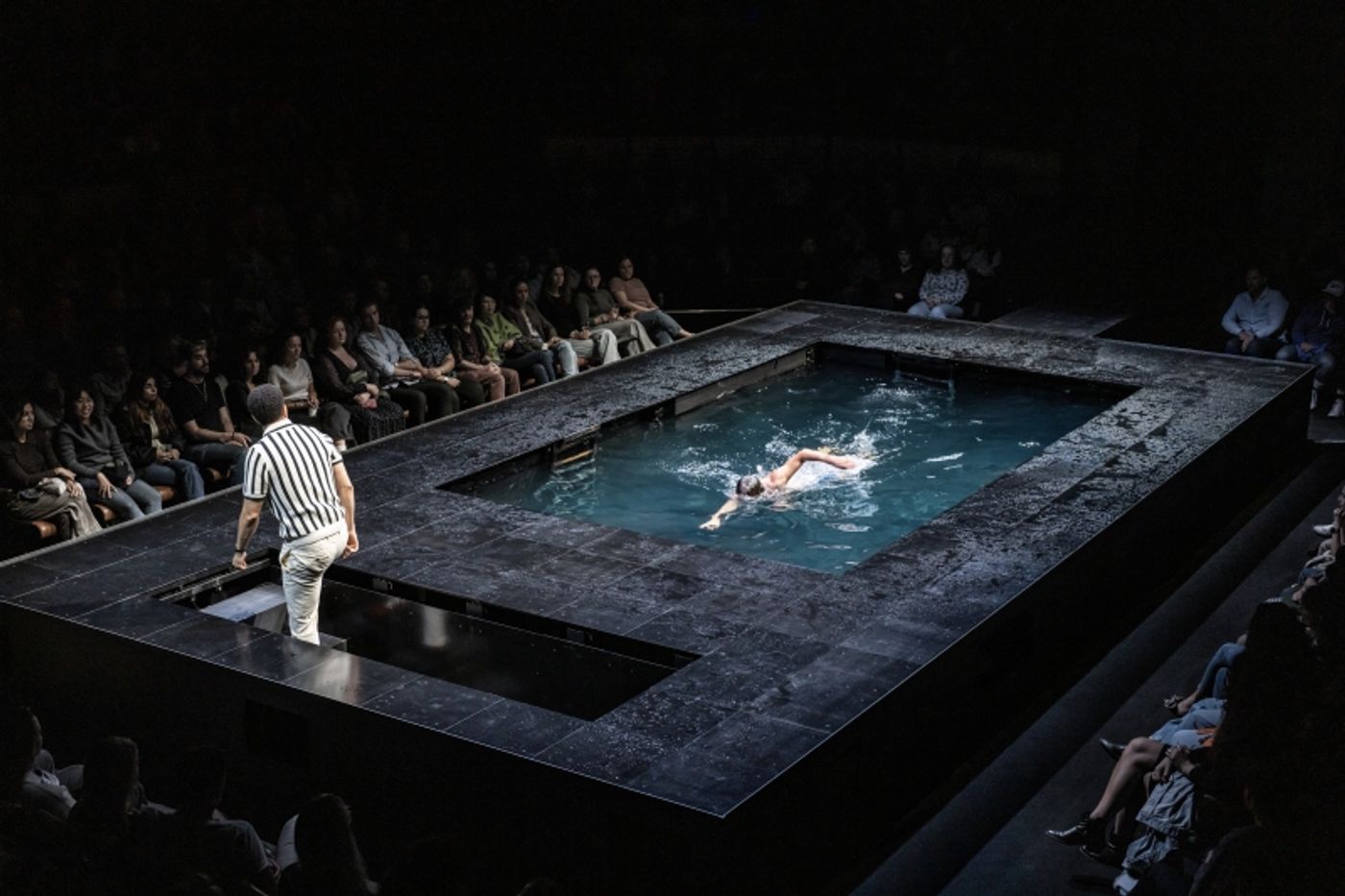

If the first act is all sharp jabs and tongue-in-cheek remarks, the second includes a checklist of societal critique anchored by intense passion and striking visuals. Besides the aforementioned exploitation of the left, we see an attempt at dissecting racial exclusion and the climate crisis. It feels like Stone is packing in a semblance of issue-led storytelling for the sake of it. It is, however, where the project fully comes into itself. Designer Lizzie Clachan floods the stage with real rain so that each pair can have their epiphanic heart-to-heart before it turns into a lifesize pool. It’s all very cool, moody, and wet, slightly dipping into the vibe of a music video to extricate feeling.

Though the writing translates Ibsen’s central themes relatively well, Stone relies on circumstantial references excessively throughout. Mentions of TikTok trends, Instagram accounts, and OnlyFans are only the start, with the script quoting from literature and cinema freely to carry the action and remarking on the situations. Beyoncé and other starlets join the pop culture ranks, but any direct mention of superstar Taylor Swift is dodged (but, then again, her ex is in it, so). That side is really overdone, a detail that drastically tilts the scales of the final outcome.

Having this many nods could hint at the limitations of freedom of thought, but it also circumscribes the exploration of the insurmountable grief of living that they experience. Simultaneously, it allows for a layered viewing and, perhaps, discourse. This will most definitely be a divisive production. Stone’s direction can be quite extra at times, as it depends on overemotion and visual gimmickry to solidify its hold. It’s safe to say that his version of the story avoids all pigeonholing, creating a piece that defies its own narrative. It’s funny and profound, disturbing and easygoing, clumsy and polished.

The Lady from the Sea runs at the Bridge Theatre until 8 November.

Photography by Johan Persson

Reader Reviews

Videos