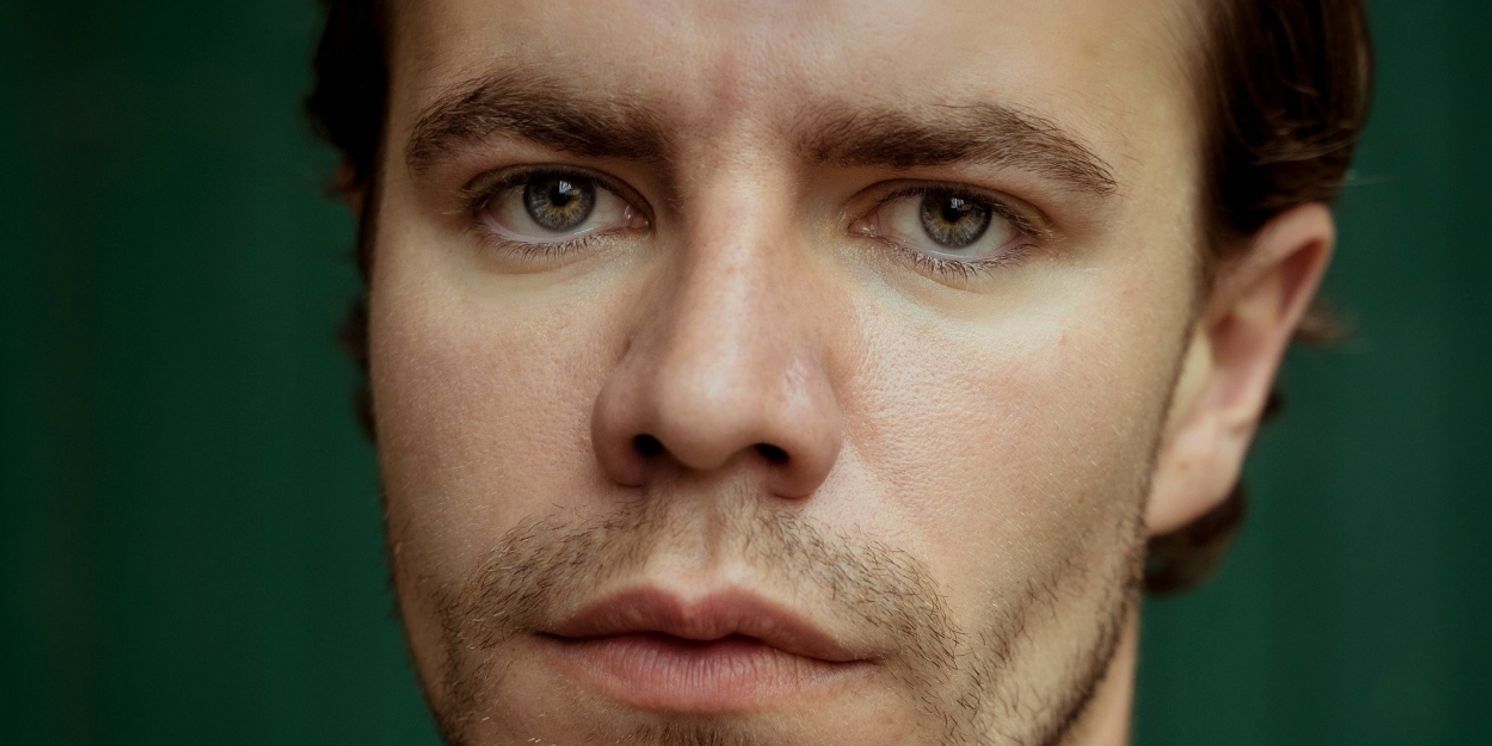

Interview: 'Masculinity Is In Crisis': Actor Oliver Johnstone on Research, Toxicity and Patriarchy in ROMANS: A NOVEL

'It's an investigation into how the culture of any particular period both shapes the idea of masculinity and is therefore shaped by it'

Alice Birch’s new play, Romans: A Novel, opens at the Almeida Theatre on Wednesday. The show, directed by Sam Pritchard, follows the three Roman brothers - Jack [Kyle Soller], Marlow [Oliver Johnstone] and Edmund [Stuart Thompson] - across five different time periods, exploring masculinity and the role that it plays in the world.

Recently, we had the chance to speak with Oliver Johnstone about playing Marlow in the show. We discussed what his research process is like for getting into character, the importance of discussing the role of masculinity in modern times and what it’s like to perform in a new work versus a classic piece like a Shakespeare play.

What made you want to be a part of Romans: A Novel?

Because it was a new play by Alice Birch - I could stop there! But I then read the script and it totally got under my skin, as did the part. Generally, the part is always the most important thing. I'm really fascinated by the character, but the opportunity to work on a new Alice Birch play was too good to pass up.

Can you tell us a bit about the show?

It's an epic story about the changing face and shape of masculinity, set over a 200-year period. And on the surface, it's about the Roman brothers - Jack Roman, Marlow Roman, who I play, and Edmund Roman - and the different paths they take in life and how they navigate their lives. But really, it's an investigation into how the culture of any particular period both shapes the idea of masculinity and is therefore shaped by it. It's easy to say, but we're at a time where masculinity is in a bit of a crisis, and Alice's play is looking at how we've got to that point as a society.

You say the play spans over 200 years. What is it like to tell that story?

Well, it makes the research fascinating, because you're not just researching one particular time period. Our characters don't end up being 200 years old. We don't have white wigs and canes, and we don't go down that road. We just jump time, the three of us. But it means that we start in a Victorian period, then we move into a between the World Wars period, then we move into the 60s, then we move into now, and then we move a little bit further down the road - just a tiny bit!

So it's meant that the research has been very fulfilling. But also, in the rehearsal room, we've been playing with form. Maybe in the Victorian period there's a more structured, recognisable thing, but then when we get to now, we can break that! We're breaking the boundaries of form by the time we get into the later stages of the play, which is thrilling.

What is your process like for becoming a character like Marlow?

Well, I should probably say a bit about Marlow, shouldn't I? Marlow is the middle brother, and, like the other two, he experiences quite a lot of trauma in his childhood. And he, as a way of coping with that, becomes very ambitious, ultimately becomes very successful, and morphs into a stereotype of masculinity that I think we'd all recognise today, which is pretty problematic.

I remember saying to Alice, when I met her, that she had done so much of the work. The way she creates characters . . . I'm in awe of it. She can do it with a line - she can create a very believable, three-dimensional human being that you understand instantly. And so Marlow was already very full. Often you play damaged characters, and it would be your job as the actor to create why it is they've become that person. But what Alice has done, in the case of all three of these men, she's charted the men they become. So actually, it makes your job a lot easier.

But it's just about finding the humanity in him, and then researching. I found it very useful to research particular people throughout history, so I've found myself researching Hearst, Rockefeller and Howard Hughes, and also people like Steve Jobs and Elon Musk, because, as I say, Marlow acquires a lot of money, and money has a profound effect on men. So it was very interesting to research.

Was there anything in particular in your research that stood out to you?

Gosh, lots! Something that surprised me was the burden of great wealth, which you don't necessarily think about if you're not stratospherically wealthy, and how people cope with that. If you achieve a certain degree of wealth, where do you go from there? Who does that make you and how do you still find life interesting? In the case of Marlow, where he's still trying to fill a void, in many ways, that's where the problems start. He achieves great success and wealth and still wants more because he doesn't feel complete again - not that he would see it like that! But that kept coming up in my in my research of very powerful, wealthy men. This insatiable appetite for more. It's quite chilling, really.

What is it like to perform in new works like this versus more classic works like Shakespeare?

Well, the opportunity to create and shape a character is the difference. Obviously, with classics, you have the opportunity to put your own stamp on it, but when it comes to new work, depending on how receptive the writer and director are, you can actually shape to a degree. Alice has been very receptive to ideas that we've all brought into the room, as has Sam Pritchard, our director. You're creating a brand new piece of work, which is trying to say something about this present moment. Rather than a classic having resonance, new work has meaning. And it's a real privilege to be able to be part of a play that has meaning and is saying something so directly to the audience, and is encouraging the audience to really engage with with very present issues.

I can imagine it's had some impact on performing as well, exploring these themes of masculinity!

Definitely. It's something that I was interested in anyway. It's a funny one, actually, because I really believe in the message of the play, and it's very important in its analysis of why masculinity has become so problematic. The phrase “toxic masculinity” gets thrown around a lot, and it feels like it's become a bit meaningless. But what Alice's play is trying to do is dissect and analyse differing forms of masculinity and how they can become violent or dangerous or coercive, and how society can reinforce and sometimes reward it.

But when it comes to performance, as an actor, you have to step away from the message a little bit that you focus on quite a lot at the beginning of rehearsals. But Marlow doesn't care about the message of the play, so my obligation is to play the character. You don't forget it, but it's less present in your mind - you're more focused on what the character wants. When you're performing on stage, you're focused on who Marlow is, what he wants and what he's trying to get from the world.

What do you hope audiences take away from Romans: A Novel?

I'm pretty sure if you've been watching the play and been engaged with it, there will be a feeling of, “Okay, we've looked at how masculinity has got to this place in 2025. Where do we go from here?” How can we begin to unpick and dismantle the patriarchy, while still providing young people, particularly young men, with an idea of what healthy masculinity can be, so that they don't feel that they they have to fight to be a man, or that they don't think being a man is bad? How do we navigate those questions? I hope audiences will come away being thrilled by a really layered, incredible piece of writing that plays with form, but ultimately comes away with those questions.

And finally, how would you describe Romans: A Novel in one word?

Epic.

Romans: A Novel runs from until 11 October at the Almeida Theatre

Videos