Review: EH UP, ME OLD FLOWERS!, White Bear Theatre

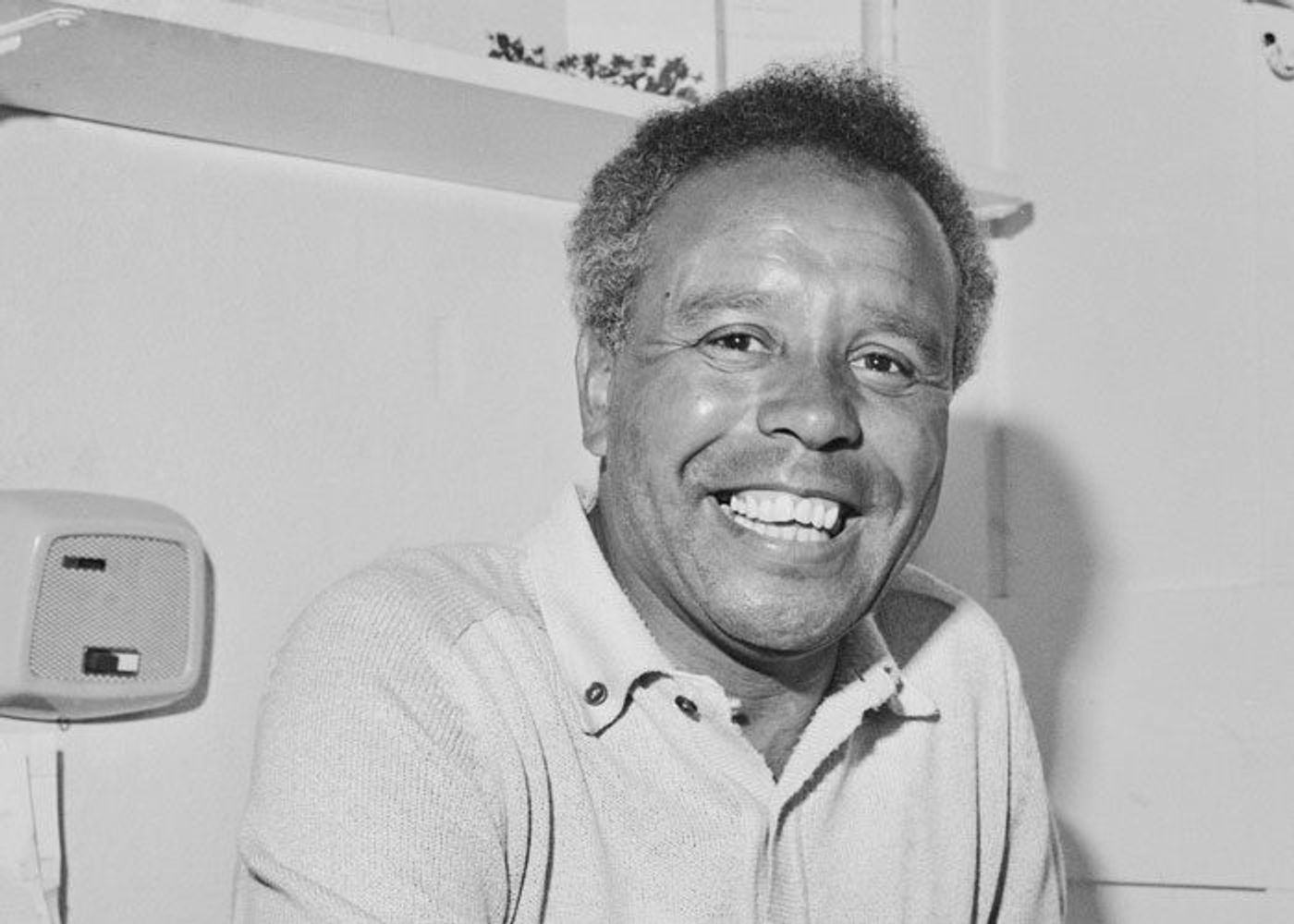

Charlie Williams, seminal Black Britiish comic, brought to life on stage

It’s hard, in the fractured environment of 21st century entertainment, to describe exactly how big some TV stars were. And few were bigger than the comics who told their gags (cleaned up, at least in some respects) on the ATV Saturday night show, The Comedians. Fast cutting from one gag to the next, it barely allowed the viewer to breathe between one laugh and the next. It also invented the playlist as an addictive format. But there’s another difference you’ll spot instantly if you load up an episode or two on YouTube - the faces, on stage and in the audience, are relentlessly white.

It’s hard, in the fractured environment of 21st century entertainment, to describe exactly how big some TV stars were. And few were bigger than the comics who told their gags (cleaned up, at least in some respects) on the ATV Saturday night show, The Comedians. Fast cutting from one gag to the next, it barely allowed the viewer to breathe between one laugh and the next. It also invented the playlist as an addictive format. But there’s another difference you’ll spot instantly if you load up an episode or two on YouTube - the faces, on stage and in the audience, are relentlessly white.

Except one. There, slotting in between George Roper, Bernard Manning, Ken Goodwin and Frank Carson, is Charlie Williams. Like most of the other turns, he enjoyed a strong uncompromised Northern accent, but that’s not what was noticed, nor, largely, what he traded on - he had another point of difference to go to. Having been a vanishingly rare black professional footballer in the 50s, he was now a vanishingly rare black professional standup in the 70s. In both cases, you could say that it took balls - and I betcha Charlie did.

Chris (An Evening With Gary Lineker) England was, as so many were, at a loose end during lockdown, so he resurrected his nascent idea to write about the black man born and bred in Barnsley, near his hometown, and made a two-hander for Edinburgh. A year or two on, expanded a little, it’s in the kind of intimate venue it needs in Kennington, with tentative plans to take it to Yorkshire itself - Clacton next please!

In Eh Up, Me Old Flowers!, Tony Marshall gives us plenty of the instantly recognisable Williams traits - the voice, the grin, the homely references (like many comics, Charlie knew if he could get the wives to laugh, he was 90% of the way there) - but it’s, wisely, an evocation and not impersonation. This perfectly judged performance avoids the production toppling into tribute show territory and allows just enough pathos to leach out between the laughs. That said, Charlie was not one to dwell on life’s vicissitudes - going down the pit at 14 tends to inoculate a man against any hint of self-pity.

Critically, Marshall captures the comforting warmth that was Williams’ stock-in-trade. He was never a threat, never moved out of his lane in his routine (perhaps just doing it at all was enough) and never ventured into politics except in the most oblique ways. At a time when the National Front, the fascists’ brand of the time, were marching in the streets with the tacit approval of a police force many of whom were flat-out racist, never mind institutionally racist, he found comforting not challenging words. And I, as most of us who were around to witness those times would agree I’m sure, do not blame him.

Nick Denning-Read has a lot of fun with a range of characters that came in and out of Charlie’s life - footballer and pal Alec Jennings, an embarrassed Australian PM, Bob Menzies, after his visa application was scandalously refused, actual Brian bloody Clough! - but his most important function is to lead a framing device that examines Charlie’s material.

In vetting him for an MBE, we get, verbatim, some of Charlie’s more, shall we say, dated stuff. Coming from a good place or not, it hasn’t aged well. It gives the play a shifting locus - it’s not an apologia, nor is it a vindication, but it is a description, from which we draw our own conclusions.

Well, that’s what reviewers do, so here’s mine. I was uneasy with Charlie’s act when I was a teenager and I’m uneasy when I see it, clipped up online, now. I saw almost no black faces growing up in a 1970s largely monocultural Liverpool (outside Toxteth) and, aside from Top of the Pops, few on television either. But, in no small part due to the brilliance of Tony Osoba and Don Warrington as McLaren in Porridge and Phillip in Rising Damp, the two biggest sitcoms in the Age of Sitcoms, I knew there was more to a black man than Charlie’s shtick.

And then, idling one afternoon in my mother’s cinema, in a support feature for a Gene Wilder buddy movie, I saw Richard Pryor: Live in Concert and, once I had got my breath back, it’s no exaggeration to say my life was changed forever.

So, without Charlie, would Lenny Henry, or some other black lad as transformed as I was, have become our Rich? We can never know, but what a tantalising prospect that is!

But perhaps it’s the wrong question. A better one is to ask whether, without Charlie, we’d have had Lenny at all.

Eh Up, Me Old Flowers! at the White Bear Theatre until 20 September

Photo Credits: Simon Fielder Productions

Reader Reviews

Videos