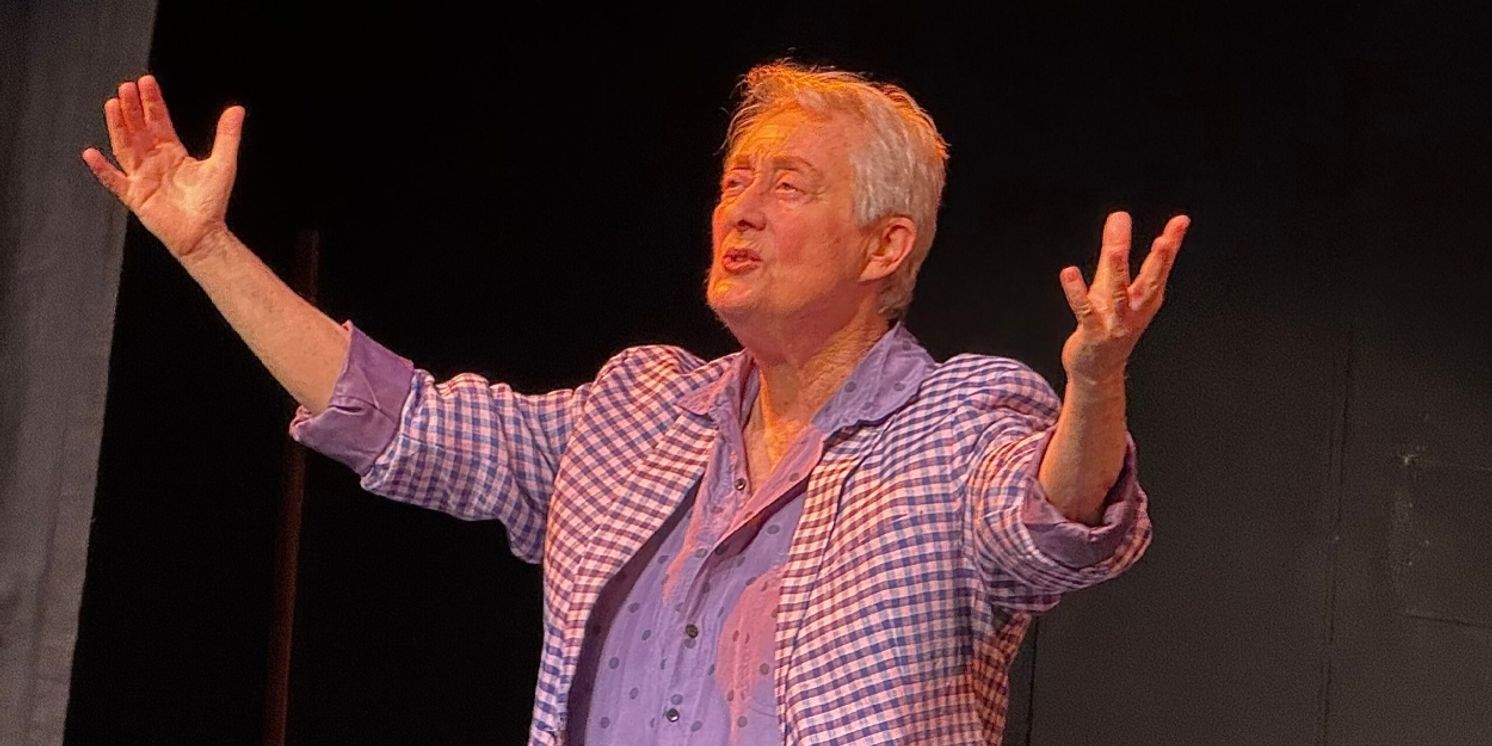

Interview: Terry Baum of LESBO SOLO: MY GAY HISTORY PLAY at The Marsh Berkeley

The pioneering playwright and performer's whirlwind tour of the gay liberation movement runs through October 12th

It’s not often that we get to see history related by the very person who made it, but that’s the case with pioneer lesbian playwright Terry Baum’s Lesbo Solo: My Gay History Play, which she is performing on Sundays at The Marsh Berkeley through October 12th. A Best of Fringe winner at the 2024 San Francisco Fringe Festival, the play begins in 1963 when Baum’s favorite high school teacher is threatened with being fired over rumors that she’s a lesbian. Spanning over five decades, Lesbo Solo: My Gay History Play operates as both a coming-out story and gay historical opus. Baum takes the audience on a whirlwind tour of the gay liberation movement shared from her own hilarious and deeply moving personal experience. As Baum notes, “It’s really astonishing, the changes that have happened in our lifetime. I witnessed that and also helped make those changes, so that’s pretty cool.”

I spoke to Baum over the phone last week to chat about Lesbo Solo and the transformative life she’s led. There’s simply no one who’s had a career quite like hers. A seminal lesbian playwright and performer who has been making theater for fifty years, she’s toured all over the world and won countless awards. She grew up in Los Angeles, but her deep Bay Area roots go back to being a founding member of Lilith Women’s Theater here in 1975. A fiercely engaged citizen, Baum has even run for political office in San Francisco – twice. In conversation, she’s as direct and to-the-point as I had expected, but she also exudes the kind of infectious positivity more typical of an artist just starting out in their career. As she says, “I still have a lot to do.” The following has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Lesbo Solo is the kind of show you have to have first lived before you can actually create it. Is it something you’d been planning to do for quite some time?

No, not at all. It happened in a very serendipitous way. I hadn’t performed since before the pandemic, and the San Francisco Fringe Festival is a lottery, so I decided “What the hell – I’ll throw my hat into the ring with the lottery.” You have to just submit a title, and I had done a play when I toured South Africa that was a combination of different scenes from my shows, and I called it “Lesbo Solo.” So that’s the title I submitted.

When I started working on this show, I intended to do what I had done in South Africa. But I had one autobiographical piece about coming out as a lesbian, and it kind of kicked all the other scenes out of the show [laughs] and I wasn’t expecting that. Gradually it became a show about my experiences, my story, as it interacted with the struggle for gay liberation over the last 50 years.

It begins in 1963 when I’m in my class in high school with my favorite teacher, who is having a kind of a nervous breakdown because there’s rumors that she’s a lesbian – and I didn’t even know what the word meant at that point. It goes on from there with me exploring who I was and what was happening in the world, and sometimes I happened to be where something really important happens, like the 2nd Congress to Unite Women, where lesbians who had been purged from the women’s movement demanded their rightful place in it. I wasn’t a lesbian at that time, but I happened to be there and witness that, and it was a major turning point in the women’s movement.

I never had an intention to write this show, but I discovered that it meant a lot to people. It just so happened that I’ve had this amazing life and was part of this incredible transformation for gay people.

It’s one thing to have led an amazing life, but it’s another thing to turn it into a piece of theater. How did you go about doing that?

Well, I’ve been a playwright for a long time, but everything has been fictional until the last play I created, Hick: A Love Story, so that was maybe my training for it – creating a structured play out of all the evidence of Lorena Hickock’s lesbian relationship with Eleanor Roosevelt. That was in a way a similar to creating Lesbo Solo, somehow synthesizing this mess of two people’s lives and making a dramatic structure out of it.

My job was made more clear in the end by something that had happened to me before I even thought about Lesbo Solo. The oldest gay synagogue in the world is near my parents house in LA, and I visited it and discovered that my old high school teacher was an honored elder there. So the whole arc of Lesbo Solo is personified by the journey of Miss Pearl, who had to lie and humiliate herself in the beginning of the play. I didn’t know she was a lesbian, in fact I had no feelings of myself as a lesbian. I thought it was terrible if she was a lesbian, you know that she should be fired, even though she was my favorite teacher.

Then I discovered that in fact this woman was forced to lie about herself in front of the class, by denying that she was a lesbian in order to keep her job, because that was the reality for gay people in the 60s. That’s what they had to do. I mean, it was understood in the gay community that if you were at work and somebody said something homophobic, you had to say something more homophobic, to deflect any possibility that anybody would think about you. That was normal. You had to call yourself disgusting, in public, in order to survive.

The play covers your journey from homophobic teenager to outspoken lesbian. How did that homophobia show up for you as an adolescent?

Well, I would say I was pretty repressed sexually as a teenager, but I was horrified by the idea of lesbians. I mean, lesbians were inherently evil, there is that in our culture. Like Jean-Paul Sartre in his famous play No Exit, three people are in hell because of the horrible things that they’ve done. One of them is a woman who killed her baby, the second one is a man who committed treason during the war and betrayed his fellow soldiers, and the third one, the horrible thing she did, and Sartre represents is as really the bottom of evil, is she’s a lesbian! She fell in love with a straight woman who left her husband. Sartre himself had a lot of affairs with married women, but the ultimate evil in his mind was a lesbian who had an affair with a married woman. That was it.

So those things were powerful for me, and they affected me. I never thought I would be a lesbian. I was not an unconventional child, I didn’t question the idea that to be a lesbian was to be inherently depraved and evil. That was generally accepted.

How did you get past your own homophobia?

I guess it was a slow thing. It was first becoming a feminist, absolutely, that was a step toward coming out as a lesbian. And then it was wanting something more in my relationships with men, wanting intimacy that I could not find with men, a really deep connection. It was very much combined with feminism for me.

Thank god the feminist movement was happening at the time.

Yes! And I was kind of the first feminist on my block. I only say that because I remember my friends would bring their boyfriends to talk with me. If I had a girlfriend who had a boyfriend and she wanted him to get a basic understanding, then he would be brought to me and I would have a conversation with him, you know a very friendly conversation. But I was that person for my friends. [laughs]

Where was this?

Manhattan, Upper West Side, in 1972. And that was really a powerful, startling thing. Like I say in the play, “When I grew up, everybody said ‘We live in a democracy. Any boy can grow up and run for president.’” Nobody thought anything was wrong with that statement, and I didn’t, either.

I remember being told that same thing, over and over again.

Really, you do, too?

Yep, and I grew up in small towns in the Midwest, so I thought maybe that was just the case there.

Yeah, well, I grew up in Los Angeles – a big, sophisticated city - and I heard the same thing. It’s really astonishing, when you think about it, the changes that have happened in our lifetime. It’s amazing. I witnessed that, and also helped make those changes. So that’s pretty cool.

You twice ran for political office. What was that experience like?

Well, I’m a big believer in participating in democracy, and I believe a lot more people should run for office. That’s something people don’t even think about. “All those other people do that. Oh, they’re all a bunch of crooks. Why should I want to be a crook like them?” No! Spending tax money and making laws is real power, and we need to participate more in who has that power. So I ran against Pelosi in 2004 because she supported the invasion of Iraq. That was a very frustrating experience – but running for mayor was so much fun.

Really?

Oh, yeah. Because for city offices in San Francisco, there are an endless number of forums that candidates are invited to, to speak. I actually didn’t really have much chance of winning, but I got to speak in these forums with other candidates and got my ideas out. In fact, I remember going and looking at the door hangers on Election Day for some of the major candidates and almost everything on them was from my platform. My campaign manager was furious, but I was thrilled that other people who have more power than me had adopted my ideas, like Clean Power SF. Immediately after the election, even though the person who won for mayor was not a progressive at all, Clean Power SF started happening, and I felt I was partially responsible for that. And also it was really fun speaking at the forums. I said a lot of things that other people weren’t saying.

I think that’s why so many candidates seem to hate doing those forums, because they feel forced to trot out the same old platitudes rather than saying something meaningful or citing specifics.

But it all changed when I came in. Because if you’re yammering platitudes, that only works if everybody is doing it. When I came on the scene and talked about specifics, it forced everybody else to be concrete, and in fact, other candidates thanked me! [laughs] They agreed that I had elevated the level of discourse by being there. So it was a great experience, it really was.

You lived in Amsterdam for almost a decade from the mid-80s to the mid-90s. With what’s going on in the U.S. right now, have you considered moving back there?

Holland has also turned to the right, so it is not an escape. And I don’t believe in that. As citizens of the most powerful country in the world, I don’t believe that we have the right to leave and go to another country, unless we’re being threatened with arrest or something like that. I think Rosie O’Donnell definitely had the right to go, because she’s been an enemy of Trump for a long time, and she said she went because she has a disabled child. He probably hates her more than anybody else since she was the first one who called him out.

But other than that, I feel we have to stay and fight. Because if all the people who are horrified with what’s going on leave, what does that mean? Who is left? C’mon, folks! You have an obligation to the world, because unfortunately, this country is by far the richest and has the most influence. It’s obvious to me that the project now is electing a democratic majority in Congress. We all have to commit, and I’m not just talking about writing letters and giving money. You have to commit to canvassing in a swing district. I did it for a man who was running for Congress in Modesto.

There has to be this huge effort of ringing doorbells. And we can do that. Canvassing is very, very labor-intensive, but it’s the gold standard of campaigning. When people answer a door, and there is somebody there that is passionate enough about a candidate or an issue to have schlepped around your neighborhood and rung your doorbell, it makes a difference.

You’ve been a role model for so many lesbian theater artists. When you were starting out, did you have any role models yourself?

My role model is Henrik Ibsen. James Joyce felt that Ibsen created the modern world, just with the way he was thinking, the plays that he wrote and the incredible attention that he got. He had such amazing courage, again and again and again. Every single time he wrote a play, all the critics would say, “No, this time he’s gone too far!” And then eventually his plays had this force that changed society. I mean, they liberated people.

So, yeah – I’m an Ibsen person. I think plot is very important. I’m a storyteller and I’m very much about structure. I’m a pretty traditional playwright, in fact. I’m interested in experimenting in content much more than form. What am I saying that hasn’t been said, that needs to be said? What secrets do I have to tell? I feel that one of my functions is to speak the secrets that everyone else has. There was this taboo on the idea that women were lesbians because they couldn’t stand the penis inside of them, you know? [laughs] So I had to break that taboo.

At this point in your career, what do you feel is still left to be done for you?

Oh, I have so many plays to write - are you kiddin’ me?! And I also have a blog, with 700 subscribers. I’m always commenting on the world. I feel personally obligated to do what I can to save the world. I have another play, Mikva, which is in its first draft, but I’ve had readings of it. It’s about two women in a shtetl in the early 1900s in Poland. “Shtetl” is a Jewish village, and “mikva” is the women’s ritual bath, and the mikva attendant and this young women in a very unhappy marriage fall in love. That’s my play about women’s rage against men that I’ve been intending to write for a very long time.

So I still have a lot to do. I don’t have any sense of completion, at all.

(Header photo courtesy of Terry Baum)

---

Lesbo Solo: My Gay History Play runs through October 12, 2025, with performances 5:00pm Sundays at The Marsh Berkeley Cabaret (2120 Allston Way, Berkeley). For tickets or additional information, visit themarsh.org.

Videos