Review: MANHUNT, Royal Court

A rare misfire for Robert Icke, as he fails to uncover the dark soul of a notorious killer

Robert Icke, mantelpiece newly reinforced to carry the weight of awards recently hoovered up by 2024’s Oedipus, has built a reputation on finding new, thrillingly engaging ways to tell old stories. In Manhunt, his first foray into writing in tandem with directing, he finds an old, oddly disengaging way to tell a new (well, newish) story, that of the killer and short-lived fugitive, Raoul Moat.

Robert Icke, mantelpiece newly reinforced to carry the weight of awards recently hoovered up by 2024’s Oedipus, has built a reputation on finding new, thrillingly engaging ways to tell old stories. In Manhunt, his first foray into writing in tandem with directing, he finds an old, oddly disengaging way to tell a new (well, newish) story, that of the killer and short-lived fugitive, Raoul Moat.

Okay, that’s not strictly fair. He does inject some imagined dialogues - Hello Gazza - and a distressing monologue from a victim given a rare chance in this play to be something more than a punchbag (literally at times). But these narrative and theatrical flourishes are too insubstantial (we’re immediately and unnecessarily told “That didn’t happen”) to lift an approach too close to Enid Blytonesque exposition salted with repetition. What remains is an uninteresting man telling us about his uninteresting life. At one point, Moat says that had he not become a murderer, nobody would have noticed him - well, there’s probably a reason for that.

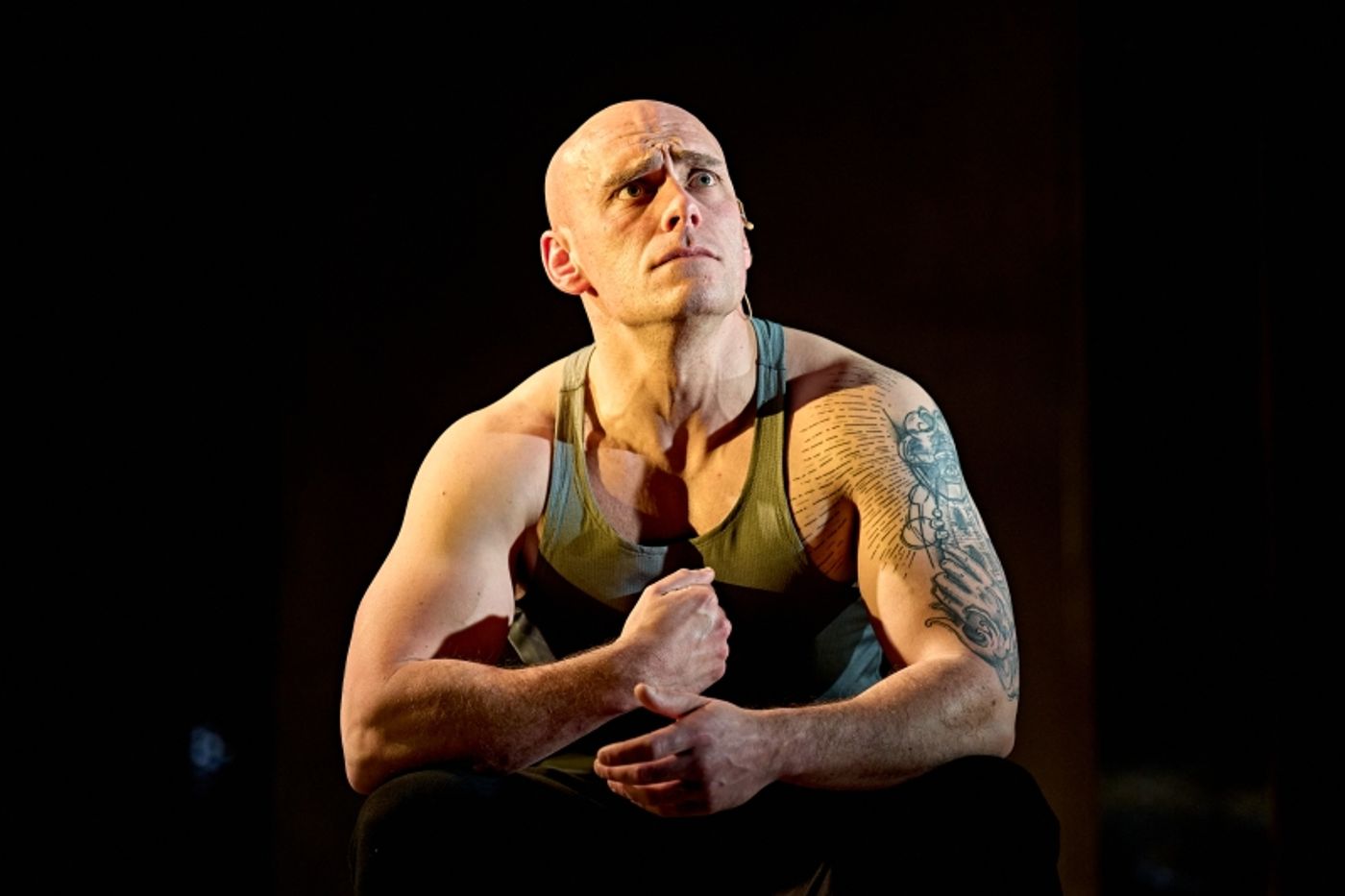

We do notice Samuel Edward-Cook, initially prowling around inside a holding pen with video projection showing him from above, looking like an animal in a zoo. It’s a sledgehammer metaphor that slides into a half-hearted framing device of a court case (again, most people in the house, including anyone reading the programme, will know Moat evaded justice by taking his own life), but, apart from an occasional reappearance of a gowned barrister, the trial trope fades away, exposition done.

Mostly, we are compelled to indulge Edward-Cook’s Moat as he seeks our sympathy for his difficult upbringing, neglected by an absent father and a bipolar mother often sectioned, his chaotic relationships introduced but not detailed and his interactions with authorities which either persecute him or ignore him. Sometimes Edward-Cook addresses us directly, vesting Moat with a surprisingly eloquent self-awareness; sometimes we see him, bulked up with that bodybuilder’s neck that grows from the edge of the shoulders seamlessly into the jawbone, in short scenes, intimidating social workers, family and police officers.

They’re mostly cookie-cutter figures, the ensemble cast given no time to develop their multiple roles beyond the working class ciphers they are in the play as much, as far as we know, as they were in real life. The two exceptions are Sally Messham as Moat’s last partner, second victim and DV survivor, Sam, and the disembodied voice of PC David Rathband, blinded by Moat’s shotgun (as we are by a long blackout), whose descent to taking his own life tantalises us with what might be a rather more interesting story.

Hildegard Bechtler does wonders to effect a set change while the lights are out for that grim interlude, whisking us to the wilds of the Northumbria countryside where Moat made his last stand in July 2010 after a week of fevered media coverage (of which we see nothing). He’s still the same person though, still seeking our approval for his overbearing sense of victimhood, still devoted to his kids, in words if not in deeds, still a frightened boy inside a grotesquely ‘roided up physique. That the man Moat had learned nothing from his ordeals may be a matter of record, but the conclusion that the character Moat appears also to have learned nothing, seems something of a missed opportunity and surely not the play’s intention.

In Happy Like Murderers, Gordon Burn’s electrifying, astonishing account of the lives of Fred and Rosemary West, another infamously evil working class protagonist was given a surreal fictionalised story that stayed close to the truth, but Burn’s genius was in bringing the Wests to life in all their psychopathic dystopia. The book’s extraordinary structure and storytelling lifted a pair of nonentities into unique, unforgettable characters who forced you to look at the limits of human behaviour with a terrifyingly new perspective.

There was never any chance of us thinking Fred West was a normal bloke, that it could happen to anyone pushed like that. But that clichéd conclusion hovers uncomfortably around the play, a calumny really on the vast majority of men in such circumstances who do not resort to extremes, even as we acknowledge the epidemic of male on female violence that continues to pollute our nation.

Manhunt (and its title is a signposting) probably had similar ambitions to catch the psyche of The People in the narrower, but definitely Zeitgeisty field of toxic masculinity, but such depth remains largely unexplored. Like police cover-ups, social workers' priorities and the mental health crisis of Boomer men caught on the wrong side of postindustrialism, it’s alluded to but not examined in a production that resurrects a man only to bury him again 100 minutes later, having said far less than it might have. And, more pertinently, far less than it should have.

Manhunt at the Royal Court until 3 May

Photo Credits: Manuel Harlan