Interview: Playwright Tim Blake Nelson Talks AND THEN WE WERE NO MORE World Premiere At La MaMa

And Then We Were No More is playing now at the Tony Award-winning, La MaMa Experimental Theater Club.

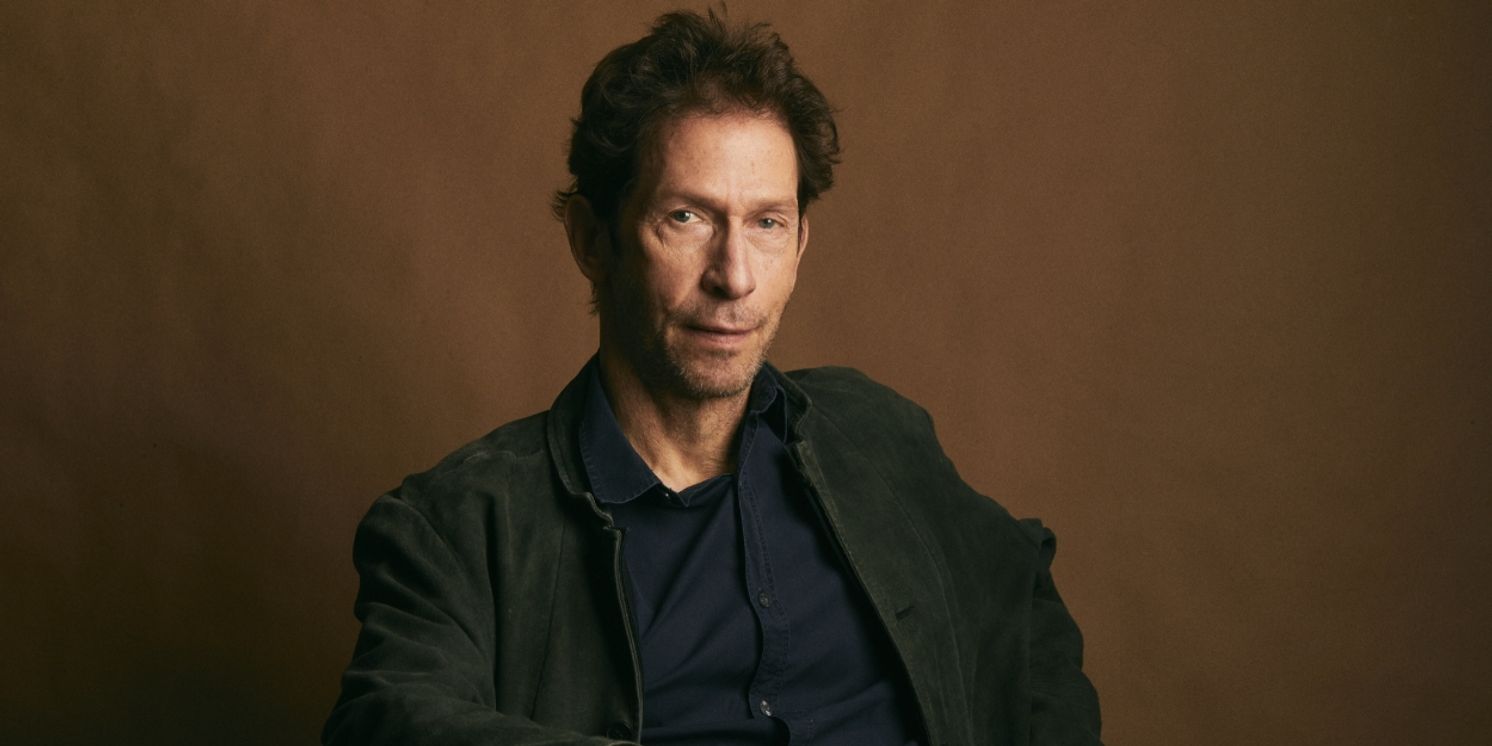

This fall, Tim Blake Nelson, a celebrated actor, writer, and director whose work spans stage, screen, and page marks the world premiere of his newest play, And Then We Were No More, playing now at the Tony Award-winning, La Mama Experimental Theatre Club.

Directed by Obie Award winner Mark Wing-Davey and led by Elizabeth Marvel, the production imagines a chilling near-future justice system where a lawyer must defend a prisoner deemed “beyond rehabilitation” and facing execution by a newly engineered, pain-free machine. The cast also features Scott Shepherd, Jennifer Mogbock, Henry Stram, Elizabeth Yeoman, William Appiah, E.J. An, Kasey Connolly, and Craig Wesley Divino.

Nelson’s writing career will also expand this year with the December 2 release of his second novel, Superhero, a sharp and entertaining exploration of Hollywood’s comic-book moviemaking machine.

Meanwhile, on screen, he stars in the gritty indie boxing drama Bang Bang (in theaters this month following its Tribeca premiere), co-stars opposite Ethan Hawke in FX’s new Tulsa-set series The Lowdown, and appears in Mona Fastvold’s The Testament of Ann Lee, which just bowed at the Venice Film Festival alongside Amanda Seyfried.

We spoke with Nelson about the inspirations behind And Then We Were No More, the differences between writing for the stage and for prose, and how his longtime collaborators have shaped this world-premiere production.

And Then We Were No More imagines a justice system using a machine to execute prisoners deemed “beyond rehabilitation.” What inspired this premise, and what do you hope audiences take away from it?

The initial inspiration came from reading Kafka’s In the Penal Colony with one of my sons. I got to wondering what sort of play it might make, and in doing so I realized that a modern iteration would be something entirely different, especially given where we are not only in our civics a hundred years later, but technologically as well. And Then There Were No More effectively spun itself out of that and became its own thing.

You’re also publishing your second novel, Superhero. How does your process differ when writing for the stage versus writing prose, and do the two forms influence each other?

I suppose they do to a degree, especially since the concern is telling a story, just as it is with writing films, which I also do. But a play is written for others to take over and embody and conceptualize, especially since I don’t direct my own material in the theater as I do with the movies I write. With a novel you write for a reader only—or a listener often these days I suppose—but with a play you write for collaborators.

With Mark Wing-Davey directing and Elizabeth Marvel leading the cast, how have your collaborators shaped the play and production in ways you didn’t anticipate?

Well, you’re mentioning two of the greats in Mark and Beth. I’ve also known both of them for more than thirty years. I went to school with Beth at Juilliard, and Mark directed me in one of my first jobs out of school. When I write a play I do so with the hope of being surprised by what others will bring to it. There’s not a keener mind for theater than Mark’s, and what I most hoped was that he would create not just a production, but an event, and he has certainly done that. In such instances actors need to rise to that level, which with Beth is never an issue, nor I hasten to add, is it with the rest of the fantastic cast. This is also very much a language play, with enormous demands on Beth in particular. She’s in the role because she’s one of only a handful of actors who can perform her part without making the writing seem overbaked. I can certainly say that if the play doesn’t work, it won’t be on Mark and Beth or this cast!

The story centers on a lawyer forced to defend someone society has already written off. How did you develop these characters, and what moral questions do you hope the play raises?

Ultimately the play is meant, even in our digital, AI age, or perhaps especially in our digital, AI age, to examine the enduring tension between utilitarianism and individual rights. To me, any empirical revision of our justice system will come down on the side of “greatest good for the greatest number,” which means we’re in serious trouble. In terms of developing the play’s most vulnerable character…a woman to be executed “without pain” should Beth Marvel’s Lawyer fail to save her, what I wanted to do technically as a writer was to write an entire part in fractured verse as a kind of linguistic counterpoint to the other characters’ hyper articulate prolixity.

Why was La MaMa the right home for this world premiere, and why does this feel like the right moment to tell the story?

To have a play up at La MaMa in an extended run is an absolute privilege. Not only is it a storied venue for challenging, cutting Edge Theater, it’s the right room for this play, giving Mark the space, especially vertically, to accomplish what the play needs. This is not, as Mark said to us on the first day of rehearsal for Caryl Churchill’s Mad Forest way back in 1992, “MacDonalds theatre.” What better venue than where the likes of Andrei Serbon, Dmitry Kremov, Anne Bogart, Meredith Monk and the like have presented their work? But without our producer, Carol Ostrow, who said to Mark and me, “If you want La MaMa I can help make that happen,” this production simply would not be.