Review: THE COLORADO SYMPHONY WITH ITZAK PERLMAN at Carnegie Hall

After 50 years the Colorado returns with a vengeance to Carnegie.

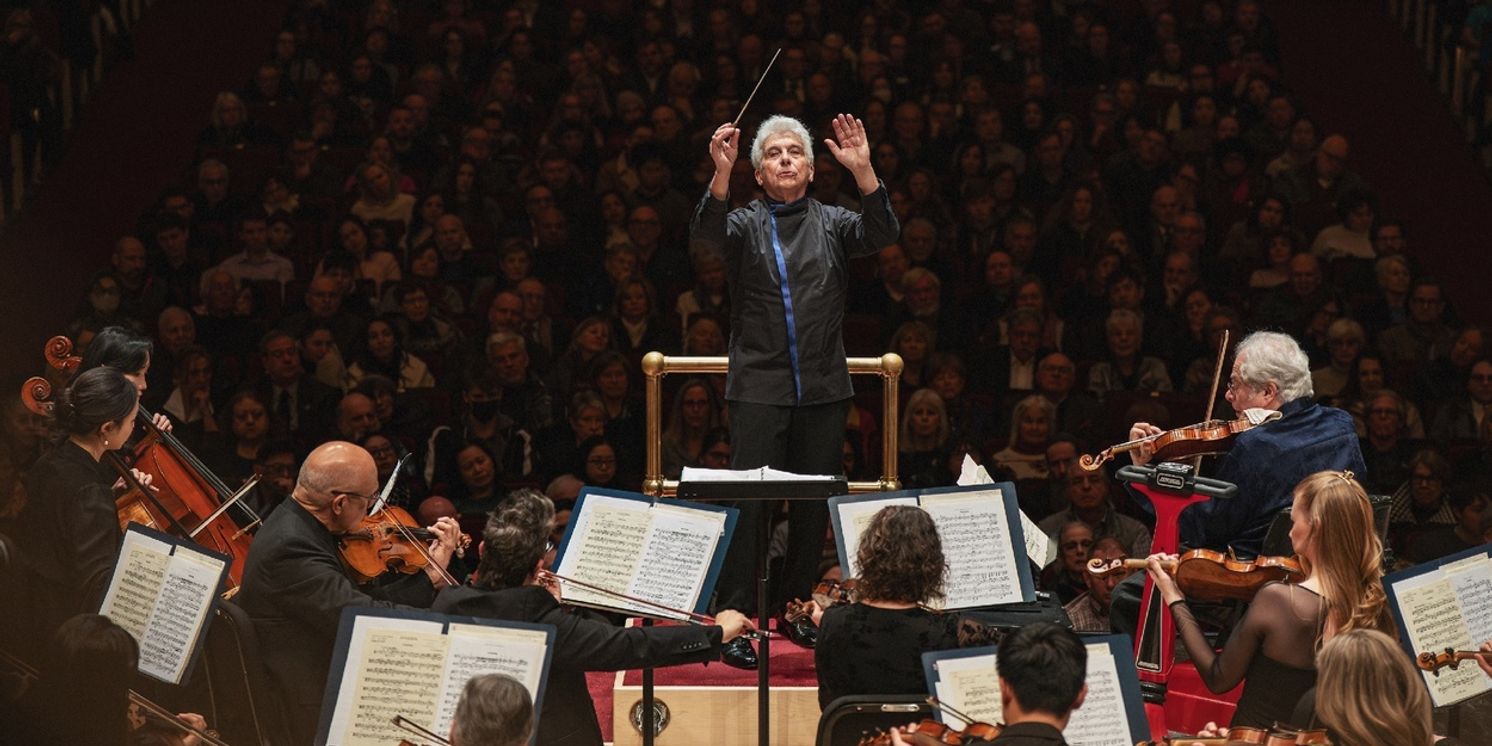

The Colorado Symphony’s return to Carnegie Hall after half a century made Sunday afternoon’s concert feel like both a homecoming and a debut—particularly striking given that the orchestra had just completed two performances at Radio City Music Hall, its first appearances ever in that iconic venue. That recent triumph lent the afternoon a palpable confidence, as if the orchestra had arrived in New York already tested, burnished, and ready to claim its place.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

With Itzhak Perlman as its warmly received guest of honor, and under the direction of music director Peter Oundjian, the program framed Perlman’s artistry with orchestral works that balanced modern edge and Romantic color—an intelligent pairing that allowed both soloist and ensemble to shine.

The concert opened with the New York premiere of John Adams’s Frenzy, a taut, propulsive one-movement symphony whose nervous energy suggests a nocturnal chase sequence shot through with film-noir tension. The Colorado players met its rhythmic demands with impressive unanimity and focus, shaping the restless ostinatos into long arcs rather than mere motoric repetition. Oundjian proved especially adept at clarifying the work’s architecture, allowing climaxes to accumulate organically and giving the quieter, suspended passages a sense of genuine release.

Perlman’s entrance was met with a rousing 2-minute standing ovation. Clearly touched, Perlman took the microphone and broke up the place with a series of hilarious quips about his very long (50-year) friendship with Oundjian. The love between them was palpable and their joy soon became the audience’s joy.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

The octogenarian violinist showed no signs of slowing down throughout the program. Dvořák’s Romance in F minor immediately transformed the atmosphere in Stern Auditorium as Perlman’s opening line—unhurried, vocally inflected, and unmistakably personal—projected an intimacy that seemed to contract the hall’s vast space. While the repertory choice may not have been among the most technically punishing in the violin literature, there could be no question about the voluptuousness of Perlman’s tone, nor the delicacy and beauty of his phrasing. Every note carried a burnished warmth, every turn of phrase shaped with the patience of a master storyteller. Oundjian kept the orchestra in chamber-like balance, allowing winds and inner strings to converse gently with the solo line rather than compete with it.

A group of shorter pieces further illuminated Perlman’s singular gifts. Kreisler miniatures, shaped with measured rubato and restrained portamento, were rendered not as nostalgic curiosities but as fully realized musical statements, their expressive character sustained by Perlman’s understated elegance. The Kreisler miniatures usually played with only piano accompaniment, sounded like lush Viennese jewels when given the symphonic treatment. Gardel’s Por Una Cabeza, in John Williams’s arrangement, leaned into a smoky tango sway, with the orchestra’s lower strings providing a sultry undertow beneath Perlman’s pliant, sighing lines.

426_7%20(4).jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

The emotional center of the program came with Williams’s theme from Schindler’s List, a work now inseparable from Perlman’s voice. Here his vibrato narrowed to a silvery thread, and gestures were reduced to their essence. Silences between phrases felt charged, and the hushed orchestral support created a collective stillness so complete that the audience seemed to breathe as one. A ten minute standing ovation followed and three curtain calls. Finally Perlman mouthed: “I have to go! I’m hungry and need to eat!”

After intermission, Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (in Ravel’s orchestration) provided a fittingly expansive close. A bit anti-climactic after Perlman performance, nonetheless, Ondjian’s forces propelled the opening “Promenade” was noble without heaviness, and what followed emphasized character over sheer volume: the grotesquerie of “Gnomus.” This writer often feels for horn players on sub-zero temperature days, and Sunday was no exception – the hall was cold! And the brass section did allow one or two sour patches slip through, but it didn’t effect the atmospheric suspension of “The Old Castle,” and the snarling momentum of “Baba-Yaga” which were all vividly etched.

In “The Great Gate of Kiev,” Oundjian resisted bombast, opting instead for grandeur built through clarity and proportion—an approach that allowed the final pages to feel inevitable rather than inflated.

Fifty years may have separated the Colorado Symphony’s appearances at Carnegie Hall, but Sunday’s performance made a compelling case for a much swifter return - here’s hoping we won’t have to wait nearly that long to hear them again.

-Peter Danish

Reader Reviews

Videos