Review: HERSH DAGMARR: INDEFINITE LEAVE TO REMAIN, Crazy Coqs

The French singer breathes new life into the Pet Shop Boys repertoire

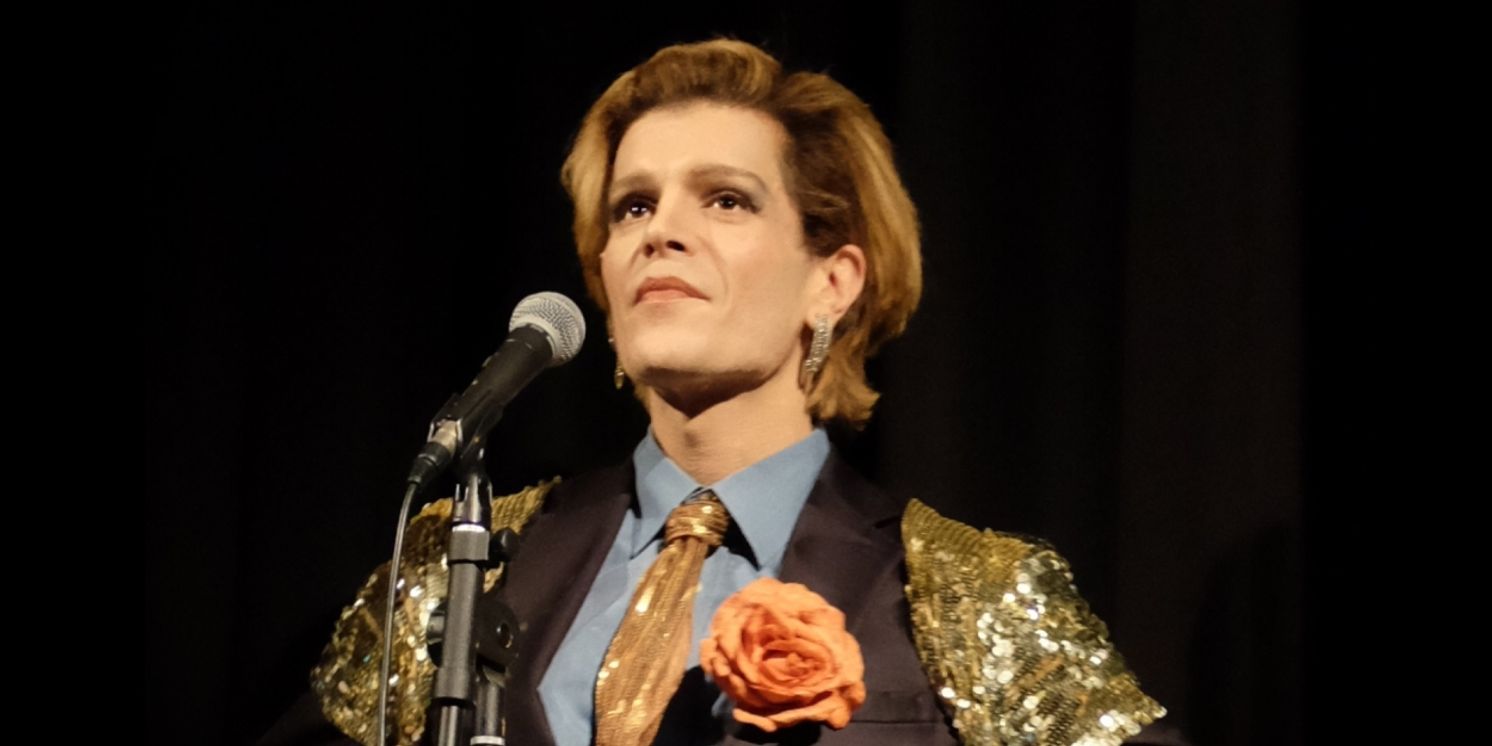

![]() With Indefinite Leave To Remain, the singular Hersh Dagmarr lifts and shifts the hits of The Pet Shop Boys into a cabaret setting. It is a curious creature of an evening: part musical theatre, part confessional, and lashings of his rambling yet magnetic dialogue.

With Indefinite Leave To Remain, the singular Hersh Dagmarr lifts and shifts the hits of The Pet Shop Boys into a cabaret setting. It is a curious creature of an evening: part musical theatre, part confessional, and lashings of his rambling yet magnetic dialogue.

In the Crazy Coqs, a venue that feels both intimate and theatrical, Dagmarr paces the stage in a lurid unseasonal ensemble—black fur cap perched rakishly atop his head, a matching black fur jacket that seems more attuned to Siberian nights than a midsummer’s soirée. Even when pulled halfway down, it is a sartorial gambit that teeters on the edge of camp and disaster, its very incongruity mirroring Dagmarr’s own propensity to veer off-script into asides and digressions that, while never dull, often feel as if they might tumble into oblivion before finding their way back to coherence.

Central to the purpose and success of this show is the notion that cabaret, that protean art form born in smoky backrooms and proletarian salons, can re‑interpret the repertoires of great artists like Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan or Neil Tennant who, despite being phenomenal writers, couldn’t be said to possess the greatest of voices. In the right hands, a song bursting with incisive or insightful lyrics can burst into new life. Although (sometimes rightfully) maligned as “posh karaoke, it is cabaret’s great magic to turn limitations into signatures, and one that its proponents embrace wholeheartedly. Well, that’s the idea at least.

In Dagmarr’s hands and through his pianist Karen Newby’s arrangements, the PSB classics lose and gain in equal measure. Jazzy overtones give the darker numbers a less introverted feel, opening them up to a more convivial delivery. Revitalised works like “Opportunities” and “Rent” that railed against the brazen capitalism of the Eighties find new purchase in these times: the former brings to mind the grasping likes of Thames Water and those who financially abused Covid-era schemes while the latter is a reminder that rent is not merely a bill but a fracture line across generations.

On the flip side, Dagmarr rarely embraces the dramatic direction of the originals. The coyness of “Left To My Own Devices” and the Tennant’s arch “Being Boring” are missing in action, leaving something plainer and decidedly less delicious in their place. “West End Girls” rattles past like a bullet train devoid of its snarling punchiness.

There’s no doubt that Dagmarr is a fine performer but whether he is suited to the more intimate and introspective environment of a cabaret space is debatable. He rarely stops to build rapport with the audience, even those at his feet. He stares down between songs and rarely meets the eyes of those sat at the small, round tables. There’s a surreal poetry in his clothing but his manner seems over-rehearsed and formally informal.

Dagmarr’s voice undoubtedly has range. On the quieter numbers, it quivers and cracks with the fragility of a man who has lived too many lives. There’s a studied vulnerability in there which occasionally imbues his renditions with an acute poignancy. Elsewhere he can growl with the best of them, hold a note with a mother’s grip and his brief stabs at falsetto could give Martyn Jacques a run for his money. Too often, though, there’s a sense that he would rather be singing in a music hall or on the West End, the subtlety in the original delivery or lyrics lost in his forthright middle-distance foghorning.

The French singer’s loquacious meanderings wind their way through reminiscence, theory, and tangent with an almost stream‑of‑consciousness abandon. He dissects the nature of exile, the burden of memory, and the tiny revolutions of the heart—only to interrupt himself mid-thought with an anecdote about a childhood cat or a bar in East Berlin. There is something undeniably charismatic in the verbiage, even when one senses that a tighter director’s hand might have sharpened the monologues into more focused demolitions of the fourth wall. Instead, we are left in delicious suspense, caught between impatience and fascination, as each digression reveals fractions of his inner life.

At the piano, intrepid accompanist Karen Newby brings her formidable German-speaking precision to bear. In her fingers, the keys tickle into life with crystalline clarity; in her occasional asides—spoken in melodic German she intersperses like sighs between numbers—Newby becomes a duet partner not only musically but narratively. When Dagmarr falters in his speech or loses the thread of a story, Newby’s side-long glance and soft pianissimo introduction reel him back into the present moment.

His Gallic loucheness and her Teutonic sharpness create a complementary interplay that suggests an almost marital rapport: he, the lyrical eccentric; she, the disciplined anchor. It’s a dynamic that pays tribute to cabaret’s storied tradition of singer‑pianist symbiosis, even as it hints at underlying tensions between spontaneity and precision.

If some might critique the show’s excess of verbal preamble—those song introductions which, much like the red burlesque pasties Dagmarr dons in the second half, feel over‑the‑top and conspicuously unnecessary—they are not wrong to highlight the theatrical bravado on display. The pasties, glinting scarlet under stage lights, seem almost a cheeky protest against his earlier fur‑laden solemnity.

Yet they also serve as a visual punctuation mark to the evening’s dive into desire, performance, and the self‑created mythologies we cling to. But the moment Dagmarr steps into the wild second act, there's a strong suggestion that the wardrobe absurdities—the fur that should never meet July, the jewel‑bright pasties—are integral to his commentary on identity as costume.

That said, one yearns for a more delicate touch. Often, the song introductions feel like elaborate theatrical digressions that pad out the 75-minute runtime without adding much meaning. Dagmarr narrates mini‑tales of love affairs that may or may not have occurred, nods to Christopher Isherwood and I Am A Camera (John Van Druten’s play which was the basis for the musical and film Cabaret), and philosophical footnotes around Brexit that thicken the air but rarely advance the emotional narrative. If only half of these expositions were excised, the momentum might be more propulsive; as it stands, the evening’s pace ebbs and flows like a sea of sentiment that sometimes loses the lifeboat of concision.

Yet no quibble can sully the triumph of the finale. Dagmarr’s rendition of “Rent” is a revelation: stripped of its Broadway grandeur, the anthem of youthful yearning emerges in a raw, trembling form. His voice, buoyed by Newby’s powerful accompaniment, cracks on the chorus in precisely the right moments. And when he follows with “It’s A Sin”—without its dance‑pop veneer and recast as a mournful lament—it becomes a dirge for every soul exiled by shame. In these two closing numbers, everything coalesces: the rambling dialogue, the costume theatrics, the lengths to which cabaret can stretch a melody, and the strange beauty of a voice that knows how to break.

In sum, Indefinite Leave To Remain is an evening of glorious contradictions. It is both over‑long and immersive, fashionably anachronistic and fiercely contemporary. Hersh Dagmarr emerges not as a flawless vocalist or actor but as a cabaret auteur, one who in his way courts chaos and indulges in theatrical excess.

Hersh Dagmarr returns to Crazy Coqs later this year.

Photo credit: Hersh Dagmarr

Reader Reviews

Videos