Guest Blog: 'Horror is One of My Favourite Genres': Playwright Nancy Netherwood on Exploring Possession and Exorcism in Her New Play RADIANT BOY

'What’s frightening is in the room with you, and it’s happening right now.'

Horror is one of my favourite genres, and one of cinema’s most profitable genres, but it’s still rarely attempted on stage. There are a handful of big horror stage hits - 2:22 A Ghost Story, The Woman in Black, Ghost Stories - which are gripping and entertaining, but tend to be, as the titles suggest, a particular kind of ghost story, operating on a system of jump scares, sudden blackouts and pre-recorded screams.

While subgenres like body horror and found footage might be tricky to pull off on stage, it’s always seemed strange to me that we don’t see more psychological horror plays. Theatre is so brilliantly suited to claustrophobic character drama and exploring unstable reality and psychology, and the intimacy and immediacy of a theatre space brings the audience even closer to the horror - there’s none of the convenient distance you get at the cinema. What’s frightening is in the room with you, and it’s happening right now.

Horror also offers up a brilliant tool kit of tropes and metaphors which can be used to explore stories from refreshing, startling angles, or be subverted in unexpected ways. My play Radiant Boy is, at its core, about the protagonist Russell’s very real struggle to accept the parts of himself that he’s repulsed by, and to allow others to truly see and love him as he is. It’s a narrative that could be told as a grounded drama, but to me the thrill was in using the structure of an exorcism to surprise and challenge the audience.

People will come in thinking they know what they’re going to get, and the opening of the play gives them many of those ingredients: we meet a troubled young man who goes into trances and sees strange things; his concerned but stoic mother; and the charismatic priest she’s called in to “cure” him. But the waters are immediately muddied - Russell’s relationship with the entity “possessing” him seems fraught but also strangely codependent and connected to his queerness.

The priest’s method mixes religious language with talk therapy and maybe a little too much of his own baggage. Russell’s mother loves him fiercely and wants him well, but the circumstances that led to his “possession” and the resulting resentment between them keep bleeding in.

Mining the imagery and conventions of horror heightens the real-world tensions, expressing their intensity and complexity in a way that naturalism often can’t - an audience may never have had these experiences themselves, but they will have a strong reaction; a visceral burst of violence, maybe more so than to a heartfelt monologue. And a queer coming of age story like Radiant Boy will be received differently when presented through the lens of possession.

Radiant Boy is also a play with music, and for me, music works in a similar way - it has the power to bypass the rational mind and go straight to the heart, communicating deep, knotty feeling without words. Working together, the horror and the music will, I hope, bring the audience right into the world of the emotional world play and connect them to these characters and this story in ways they would never expect.

Radiant Boy is at Southwark Playhouse Borough until 14 June

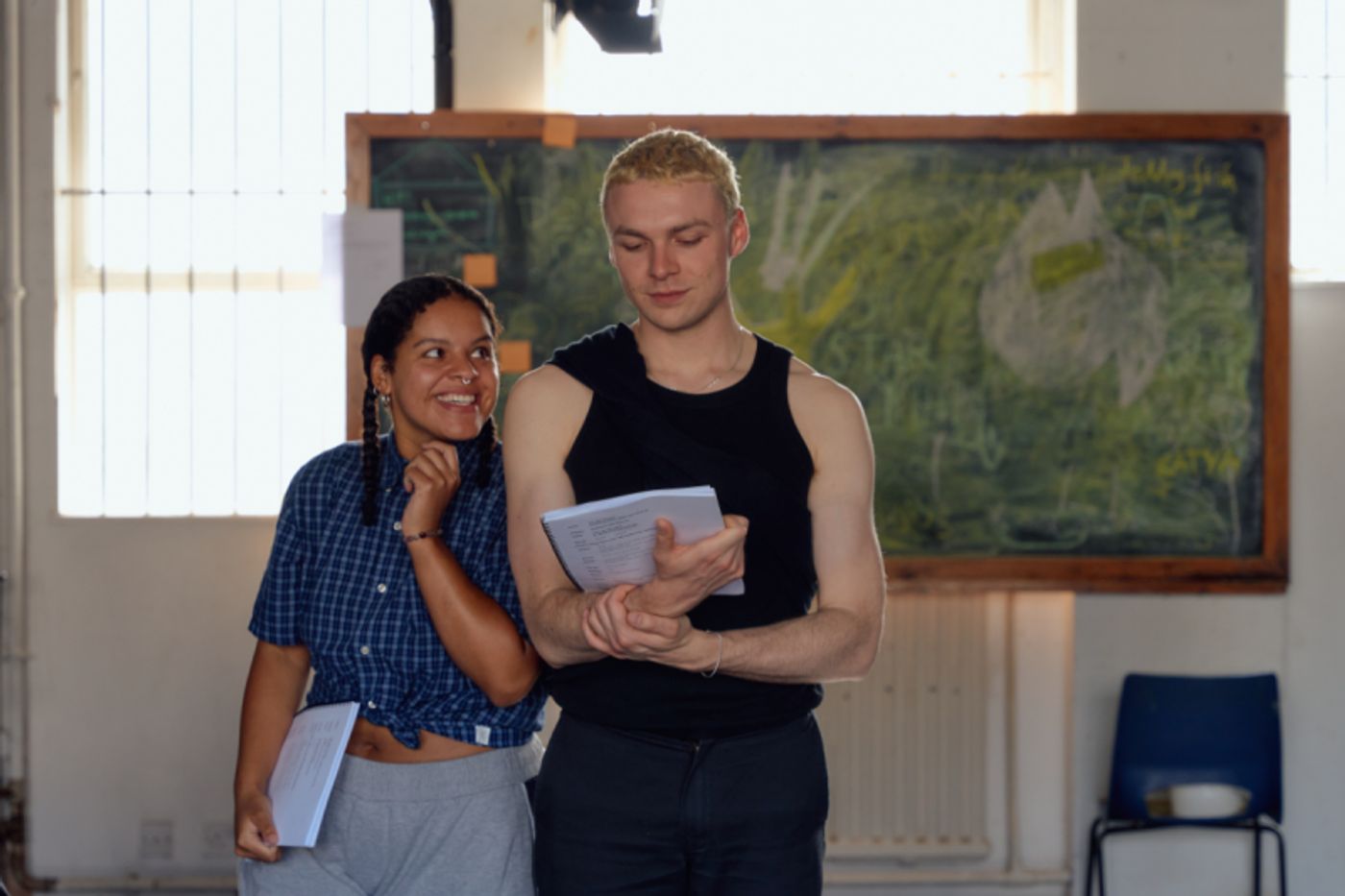

Rehearsal Photo Credits: Oli Spencer Photography

Videos