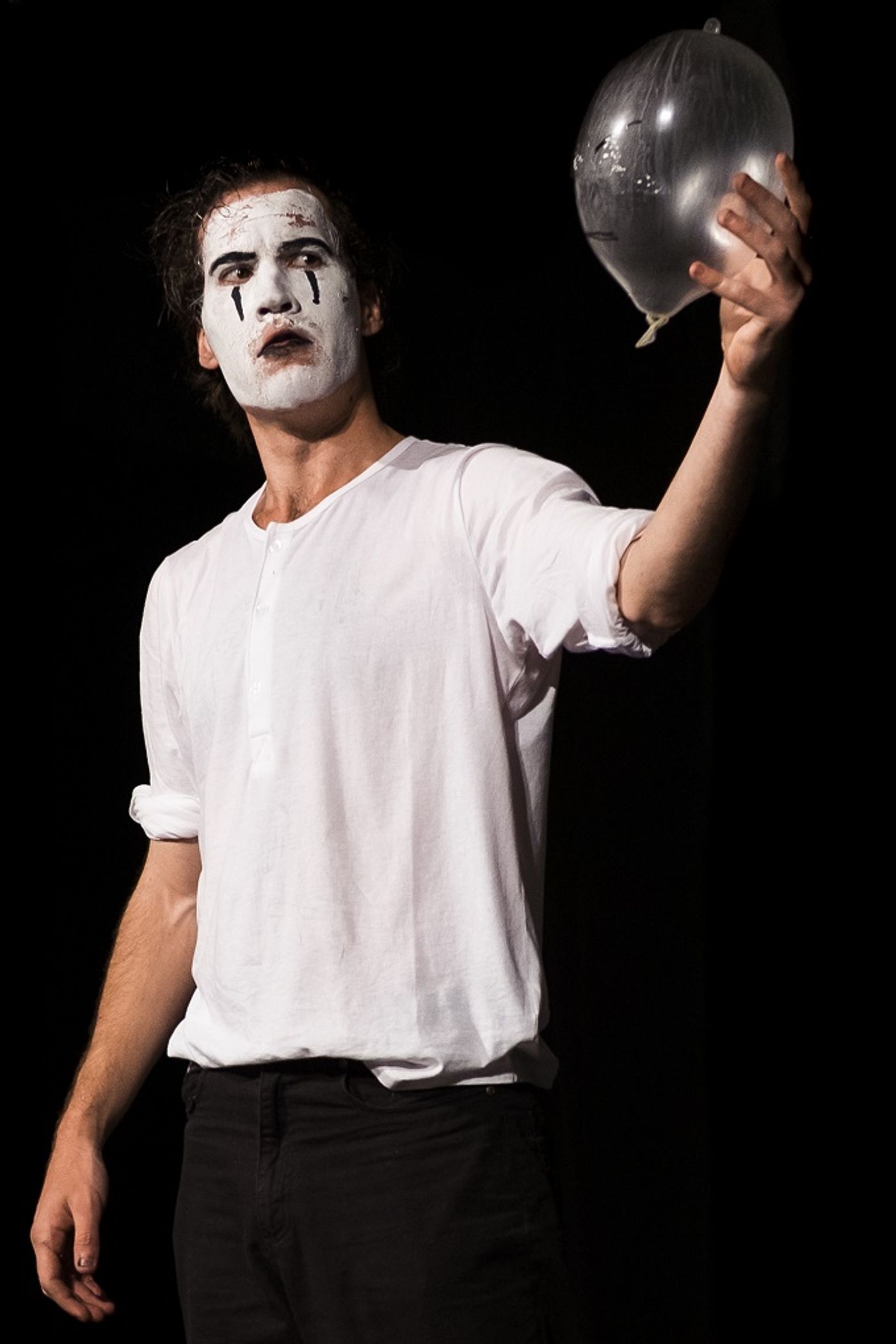

Review: A Play About Failure, DEATH OF A CLOWN Has the Makings of a Successful Web Series

Photo credit: Jeffrey Stretton-Bell/

Cuepix/National Arts Festival 2016

At the moment that an observation of the interplay between medium, genre, format and narrative in a piece of dramatic storytelling enters the consciousness, a question emerges: "Is this the best way to tell this story?" Some storytellers find the medium that suits their stories best and their work struggles to be expressed as powerfully in other media. Tennessee Williams's plays, for instance, mostly lack the impact they achieve in the theatre when translated to film. Some stories work better in some formats than others. Despite its serial nature, A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET could not make a successful leap from the big screen to television when FREDDY'S NIGHTMARES appeared in 1988. Some stories have the power to navigate the conventions of different media. FUN HOME, for example, is as moving as a piece of musical theatre as in its original form as 'a family tragicomic'. The way that Ryan Napier tells the story of DEATH OF A CLOWN, through a solo live performance piece, prompts this question, and the stalemate it reaches as an extended theatrical presentation is wrapped up in the answer.

DEATH OF A CLOWN is a play about failure. It is also about tenacity. Napier inhabits the figure of a tragic clown who tries to make an audience laugh. When he fails to do so, he attempts more and more outlandish feats in a bid to elicit an emotional reaction his viewers, which consist of two groups: an implied audience constructed from cardboard boxes that stand on stage throughout the performance and the actual audience who observes the clown performing for them while also performing for us.

Telling incongruities emerge from this setup, because Napier's performance for the real-life audience elicits chuckles throughout the 50-minute runtime of the show, responding - more or less - to Napier's pratfalls, the in-jokes about performers and performance traditions and interactions that elicit co-performance from the audience members in the front row. If the real-life audience is responding to that which transpires before them, is the thesis around which Napier crafts his piece disproved by a circular argument?

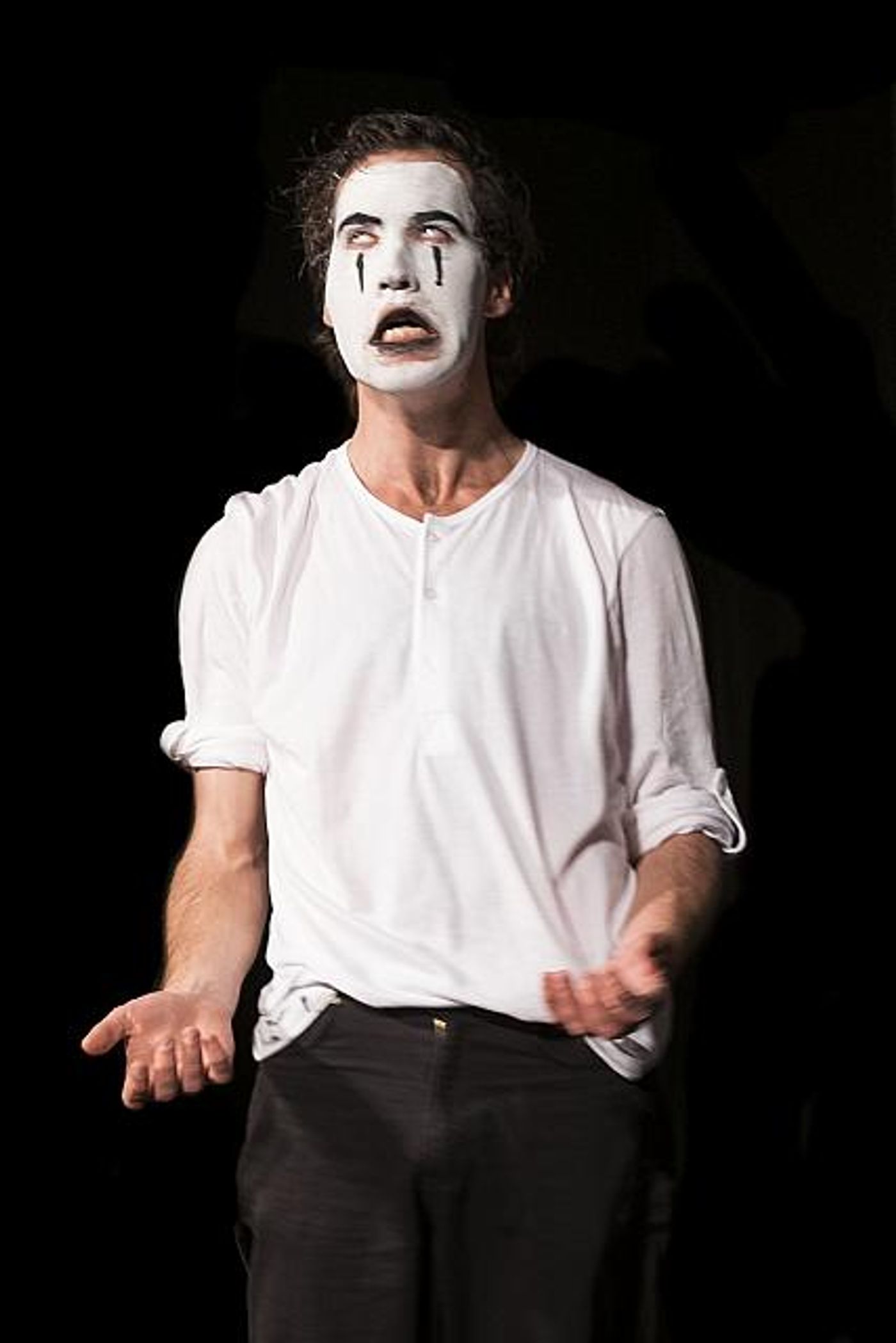

Photo credit: Jeffrey Stretton-Bell/

Cuepix/National Arts Festival 2016

DEATH OF A CLOWN sets out to be a metaphor for the challenges of opening up to an audience that is inherent in the act of performance. The piece falters by making the assumption that an audience is a homogenous body rather than a group made up of individuals, each bringing different life experiences and expectations to the theatre. Real-life audiences are not cardboard cut-outs that will always react in the same way. This assumption also infers that there is a limited range of acceptable responses that viewers may have in response to what they are watching. The placement of the cardboard figures on stage implies that audiences fail to engage with the art that they consume and that earning their engagement is a cruel and futile act. Meanwhile, the living individuals in the house respond quite actively to what is transpiring before their eyes, and the performer has caught their attention without too great an effort. Consequently, DEATH OF A CLOWN ends up being a piece about self-defeat. The failures of this clown are his own, rather than the result of his spectators' disengagement.

"You're overthinking this," a friend who saw DEATH OF A CLOWN later in the week said to me while we discussed the show. "It was simply an unassuming mime show that wouldn't be out of place at the Buskers' Festival next weekend."

She is right on both counts, but it is DEATH OF A CLOWN itself that gives one the space to consider all this, with its episodic narrative that is repetitive by the nature of its very conceit. I mused, briefly, that I would react to DEATH OF A CLOWN quite differently were it a set of serial performances, like LA LINEA, the short interstitial animated programme by Osvaldo Cavandoli from the 1970s and 1980s. There are ninety episodes of LA LINEA ranging in length from two to six minutes, and each tells essentially the same story of a character outlined in pencil whose fate lies in the hands of his animator. Popping up as they did between television programmes, one never had time to question the concept and one could enjoy each segment for what it was. In an age where the short-form web series has become popular, with the possibility of millions of views, Napier potentially has a solid-gold in his hands. And with the SABC scrambling for local content, why should short-form inserts like a DEATH OF A CLOWN web series, SUZELLE DIY or LADY ARIA GREY EXPLAINS not end up being syndicated on local television stations? Any one of these would be better programming than desperate wannabe reality shows like DIVAS OF JOZI or the disastrous gender minefield that every episode of THE MAN CAVE explodes.

Photo credit: Jeffrey Stretton-Bell/

Cuepix/National Arts Festival 2016

Despite a capable performance and some moments that land beautifully, DEATH OF A CLOWN leaves one wondering whether Napier has interrogated its central themes deeply enough to sustain almost an hour of live performance. Were the piece able to make a further leap and explore not only the difficulties of performance in life but also the complexities of social performance, the play might have more meat on its bones. As it is, though, medium, genre, format and narrative conspire to compromise the efficacy of the storytelling of DEATH OF A CLOWN. One or more of these elements needs to shift for DEATH OF A CLOWN to be everything it could be.

DEATH OF A CLOWN ran for seven performances at the Cape Town Fringe, completing its run on 29 September. The production will play a season at POPArt in Johannesburg from 3 - 6 November with bookings through that theatre venue's website.

Reader Reviews

Videos