Interview: Inside Paul Moravec's 'Method' of Composing A NATION OF OTHERS

The new work by the Pulitzer Prize winner and librettist Mark Campbell for New York’s Oratorio Society Debuts at Carnegie Hall on November 15

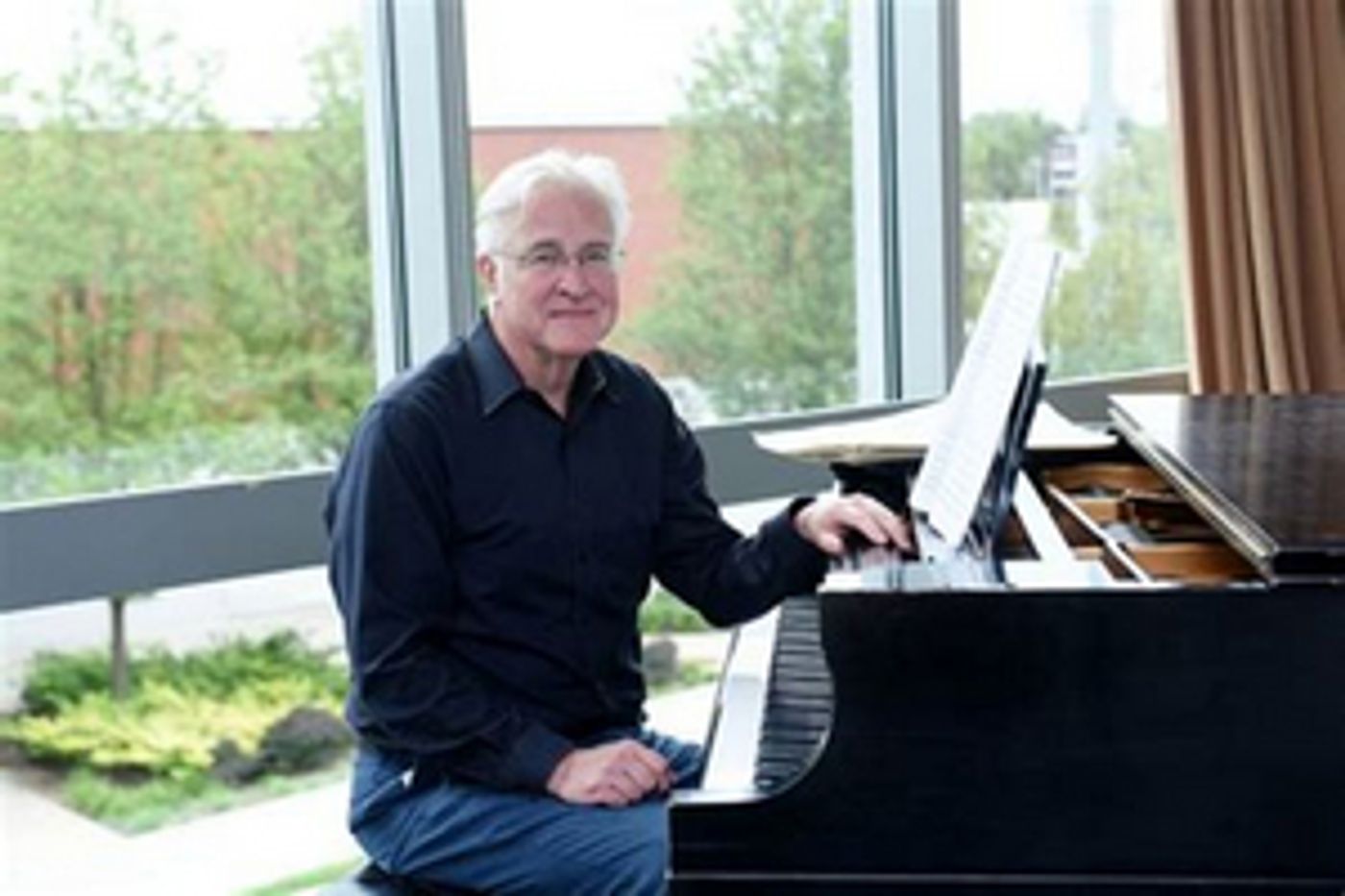

When I spoke to Paul Moravec, a Pulitzer-Prize winner, about his work on the new oratorio, A NATION OF OTHERS (which I'll refer to as NATION), debuting at Carnegie Hall on November 15, he described himself as "a sort of Method composer."

That, of course, meant before writing music, he needed to get inside the heads of his characters, understanding their inner motivations and emotions, connecting his own life to theirs--akin to the "Method Acting" technique championed by the Actor's Studio. (It may be most famous for many from Marlon Brando's primal scream--"Hey Stella! Hey Stel-la!"--in Tennessee Williams's "A Streetcar Named Desire.")

NATION, commissioned by the Oratorio Society of New York (OSNY) under Kent Tritle, tells the stories of a group of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island in New York harbor, on a certain day in 1921. Moravec's librettist is the prize-winning Mark Campbell--not only a trusted collaborator from previous projects but known for his dozens of libretti and meticulous research into his subjects before ever putting pen to paper. (Campbell's Pulitzer Prize work was the opera SILENT NIGHT, with score by Kevin Puts.)

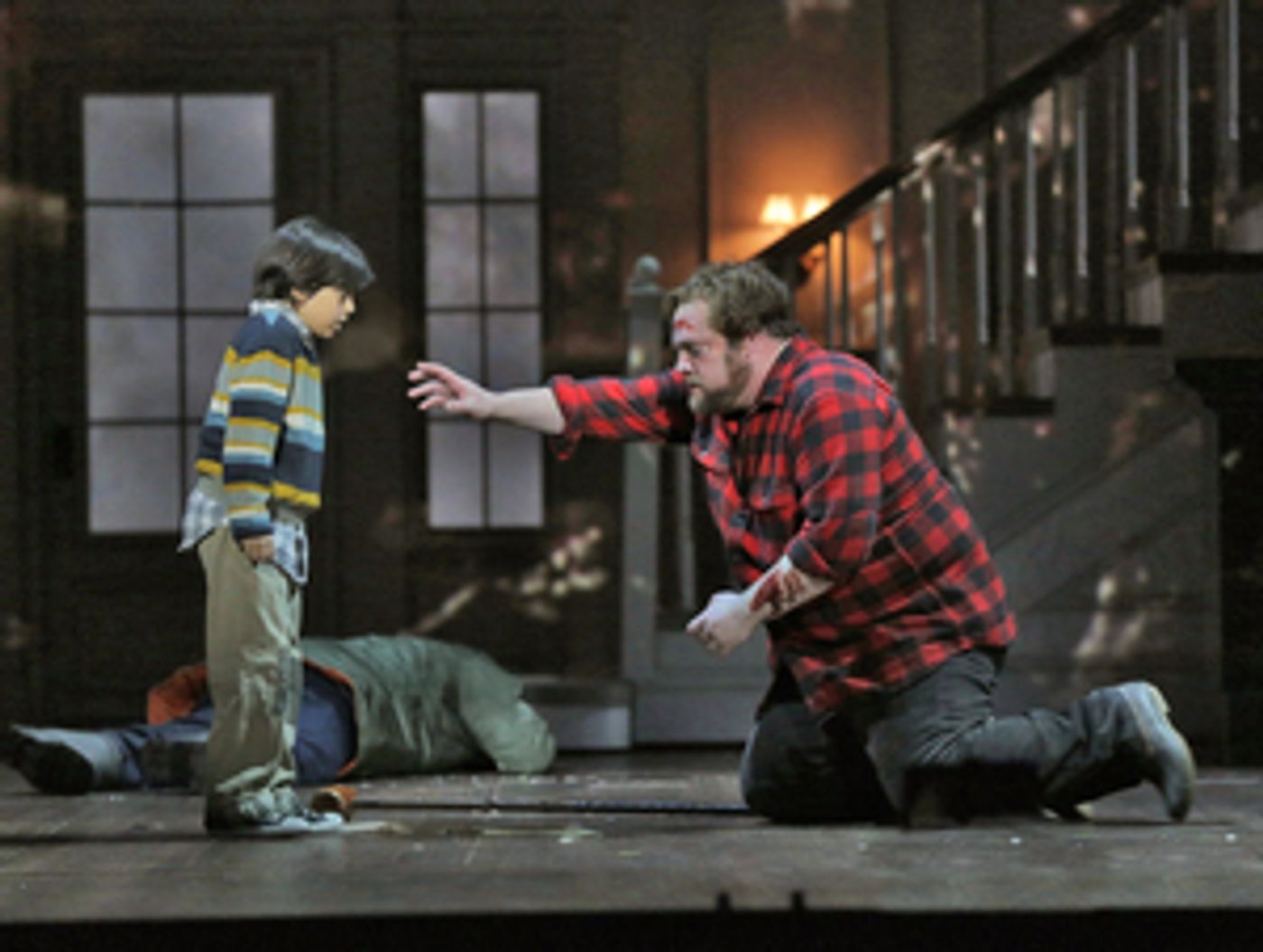

Bryce-Davis, OSNY at SANCTUARY ROAD

opening. Photo: Eduardo Patino

Shared experience

Nevertheless, for himself, the composer felt that he needed to immerse himself in what it was like for the prototypes of the people who inhabit the new work: delving into the lives of these immigrants, their shared experience of arriving by ship in New York, but their differences as well.

"The first thing I did was to make the trip to Ellis Island. It was astounding to think that my grandfather came through there in 1907 on his own, when he was 16 years old and didn't speak the language," Moravec told me. "I tried to imagine myself, traveling alone and arriving in a country I knew nothing about. I couldn't even begin to picture what it was like for him. He must have been terrified.

"For all of the promise and hope of this new life," Moravec continued, "it must have been pretty awful, coming over here but not really knowing where he was going to end up (Buffalo, NY, it turned out, where Moravec himself was born). So, understanding that aspect of the immigrant experience, or trying to imagine it through accounts that were available, was crucial to getting my arms around what we were trying to do."

Trusted collaborator

"Mark (Campbell), of course, did the actual storytelling," he noted. Campbell has become a regular a "partner in crime" for the composer, who's written around 200 pieces of music-- vocal, orchestral and chamber works. (His Pulitzer was for "Tempest Fantasy" in 2004.)

at Minnesota Opera. Photo: Ken Howard

He and Campbell wrote the successful opera version of Stephen King's THE SHINING together (using King's novel, not the film, as its source) and a previous work for the Oratorio Society, SANCTUARY ROAD, which has recently been given a second life as a staged opera at North Carolina Opera. (With its stunning rendition through words and music of the lives of African Americans who came North through the Underground Railroad, Campbell crafted his SANCTUARY ROAD libretto directly from William Still's accounts of passengers and conductors on the Railroad.)

"When we received this commission from the OSNY, it was Mark's idea to do something about immigration but it was mine to do it about Ellis Island," said Moravec. "He chose that one particular day in 1921 because it was during one of the last years that the facility was in full operation; it was after World War I (WWI), when the country was becoming more isolationist." He added, "Remember, we never joined the League of Nations and it was all part of the vibe then, including restrictions on immigration."

But it wasn't just isolationism that was a factor in the storytelling, but the general effect of the war on peoples' lives. "Many of the stories we used have to do with the dislocations of WWI, the trauma in its aftermath: the Armenian genocide, pogroms in the Ukraine, the British oppression in Ireland, particularly in Tralee (that's our Irish immigrant's story)."

(Another of the things looming over the story, though never referred to specifically, was the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. "We think our pandemic has been bad--as bad as it has been--but least 50 million people were killed worldwide by the Spanish flu, with almost 700,000 in the US alone." [The unconfirmed number of Covid deaths to-date is about 7 million.])

A single day

"For us, the idea that NATION takes place on a single day, in a single place, gives it unity. I liked the concept--compressing the experience--because you feel that the audience is experiencing these stories simultaneously. You see all these various figures coming through, telling their stories, dealing with the authorities and being checked for diseases, especially infectious diseases."

"The opera begins with a Sicilian, Tomasso, on the deck of the ship, like Tristan, singing acapella as the ship is coming into NY harbor, about why he's left Sicily and speaking in the abstract to his wife--she's still back home--about his experiences. By the time he finishes, everybody on the ship is singing about arriving at Ellis Island.

"We leave Tomasso behind but come back to him much later. So Mark begins and closes the story with this Sicilian, whom, I would say, provides the focus, though he doesn't have major solo stage time."

Bach Festival Society's premiere of Music Awake!

"The past is never dead"

"Another of the things we show in NATION is that the immigrants bring the old country with them. There's this great thing that William Faulkner said: 'The past is never dead; it isn't even past.' And that's the story of the people in NATION: They're carrying the past with them."

How to express all that in a title took the collaborators a while to figure out. "We went back and forth for days and we had a whole list of names," Moravec explained. "We wanted to avoid the obvious, like Liberty Island or Statue of Liberty--anything that had to do with the Statue we considered too corny. So one day, Mark sent me 'A Nation of Others' as a possibility and I said I'd think about it.

"I went out later to the supermarket and, looking at all the people around me, I thought, yeah, we are really 'a nation of others.' That was the perfect title because it's resonant on a number of levels.

"Ours is not just a nation of 'other people,' that look different or act differently, but a nation of 'other nations.' Clearly, the people in the story came here under duress. This was not a case of 'I'm going to pick up and move to America, this strange new country, because it'd be a nice thing to do.' No, there was something compelling making them do it--many had nowhere else to go and were really desperate," said Moravec.

"They were 'the others' in the old country, in some cases. In the case of the Sicilian, Tommaso, he'd come because things were so bad economically at home, it was impossible to raise a family there. That's why he came to America.

"That's what this piece is addresses: What is it that compels people to become immigrants?"

Moravec's style

Moravec's music has been called "expressive," "accessible" and "electrifying." Yet when I try to pin down a style that he might think categorizes his work, he says: He can't.

"Every project is different, because the materials are different," he carefully explained. "I would say that most of my pieces are tonal or 'tonal-ish,' while others are not at all--'non-tonal.' There are pieces that are tonal throughout, while others that are wildly eclectic. As I said, it all depends on the specific project.

"One of the advantages that composers have today is a very wide range of possibilities, techniques, that we can avail ourselves of on a specific project, in a specific measure. For instance, whatever you think of Schoenberg's influences, one of his gifts to us was opening up this whole range of possibilities for us to explore on a case-by-case basis--whatever is needed, I get to pick and choose the tools that I need." He laughs: "A friend of mine described 'style' as 'a collection of bad habits.'"

In common, but different

When I asked specifically about NATION, with its variety of characters who have a particular thing in common (i.e., being immigrants) but are otherwise very different, I turned the conversation to how he deals stylistically with that dichotomy.

"All the characters have their own sound world: I'm a very 'leitmotif-y' kind of composer," he explained. "For example, in THE SHINING, every character has its own collection of motifs, chord progressions and timbral things. Additionally, there's a distinction between the natural world of the human beings and that of the ghosts, who have their own bizarre sound world.

"So that's how I think, working with text and drama. NATION coheres, I hope, as one consistent piece, but within this big world, there are little sound worlds that are particular to each character."

Part of a team

Writing the oratorio as part of a team with Campbell has its own dynamic. Yes, they've written successfully before (a third for the OSNY, ALL SHALL RISE, about voting rights, is in process), but as Moravec said earlier, every piece is different. Was there anything specific about the collaboration on this one?

"Here's the thing about collaborations: words and music. The written text has its own logic, the story has its own logic, and the music has its own. But they're all separate. Different ways of thinking. It's up to the librettist and composer to join them together into one. So they're in lock step--fused together as a single creature.

"Some things are straightforward. We agreed on the subject and Mark went off and wrote a version of the libretto based on characters grounded in reality and historical records. Then he sent me the libretto--a lot of what we do is by email--and I had a reaction to what he'd presented."

A matter of trust

"Then we get down to it," Moravec explained. "Here's an example of how we work: I'll come upon a line that I don't know how to set for one reason or another; for example, if it doesn't fit into the musical logic of what I've been working on. Or, if in the process of working on a particular number--or a word--there's something that doesn't feel just right, I'd ask him for another word, another option. And he'd get back to me with it."

Moravec became increasingly animated. "It's a terrific collaboration because he's so good at this and if I can't set something--and I really try--Mark trusts my judgment and will 'make accommodations'.

"Or when I'm working on something and I send it to him and say, 'hey let's try this,' sometimes he'll come back to me and say 'no, it's not such a good idea and here's why.' He will explain in very clear language why it's not going to work. And he's usually right. That's really good. On one hand he's telling me something I don't want to hear; on the other, he saves us from going down a blind alley and wasting time and effort.

"So I think of the collaboration between a librettist and composer as the sand in each other's oyster: It can be irritating, but when he pushes back on an idea of mine, he usually forces me to come up with a better idea than I might have on my own. That's what great: An openness to change on both sides, with lots of horse-trading." And, sometimes that sand results in a pearl.

The heart of the work

He continued, "The interesting thing that happened in writing NATION, when most of the process was done and we were going through one more time, it suddenly dawned on me that we hadn't really found the heart of this story: What was it? We talked about it and Mark came up with a new number in the hospital." (Ellis Island was divided into two parts, the north and the south: the hall where the processing was done, which you can visit today, and a hospital that treated those found to be suffering from some ailment, which was considered a model of modern medicine, but is still unrestored.)

"It featured an Armenian refugee dying of tuberculosis being looked after by another immigrant, a nurse from Spain. It's the second to last number in the oratorio. And it's beautiful--what Mark's written is a beautiful scene. very operatic and very easy to stage. He provided the emotional anchor to the whole piece. So, this is an example of my saying something's missing, he comes up with an answer and I set it to music."

"...to revise divine"

How different was the final version from the original libretto that Mark handed him? "It was pretty close," says Moravec, "except for that one scene near the end that I just mentioned. Oh, and the finale, come to think of it. We went through a number of versions on that.

"Some music theatre writer once said, 'To err is human, to revise divine.' And that's pretty much the name of the game: revision, constant revision. Nothing is ever set in stone--even after the premiere. Flaubert once said, 'a work of art is never finished; it's abandoned.' He was the ultimate perfectionist--but even he admitted that there's finally a time when you need to say it's finished. That's the way I feel about a work of art--you finally have to let it go."

###

For more information about the Oratorio Society of New York's Carnegie Hall performance of A NATION OF OTHERS on November 15, including tickets, see the Carnegie Hall website.

Videos