Review: New York City Ballet's ALL BALANCHINE

This past year, while attending an extraordinary program at Paris's Opéra Garnier which featured the Paris Opera Ballet tackling, among other works, Pina Bausch's Rite of Spring, I wondered to myself, "Why is New York still the house of Balanchine?" Sure, it could be argued other choreographers have made their mark on the company, from Robbins to Wheeldon to Peck, but the basic machinery of the pieces and their executions is consistently Balanchine in a way that Paris isn't Nureyev. Lincoln Center is nearly as synonymous with Balanchine as Bayreuth is with Wagner. Happily, this past Tuesday's four-part "All Balanchine" program was an excellent justification for the company's conservation of the choreographer's composition and indelible flair.

The evening's first work, 1952's Scotch Symphony, is a compositional counterbalance to the otherwise aesthetically reduced program. With music by Mendelssohn, the work's aesthetic is firmly of the 19th century, borrowing particularly from La Sylphide, Bournonville's bouncing melodrama. However, unlike Bournonville's scope, this work has an Epcot depth of cultural understanding. It is polite, classical, and Balanchine honoring a historical tradition, rather than his own era. This isn't always cause for disaster, Tchaikovsky suits him well; however, the Romantic weight of both Mendelssohn's composition and Horace Armistead's beautiful fairytale backdrop, establish a tonal dissonance with Balanchine's watercolor frivolity. Joseph Gordon, NYCBallet's newest and youngest principal dancer, aims for charisma but achieves only a cold severity that such an unselfconscious work doesn't uphold. Ashley Bouder strums smiling through the Symphony. This work serves as a prologue to the rest of the evening's more demanding program.

Short of obvious acrobatics, most dance doesn't consciously grab my attention during its execution. It's usually in the aftertaste of a composition that the complexity of its flavors becomes tangible. This is not the case with Megan Fairchild's virtuosic execution of Balanchine at his most clever in 1972's Duo Concertant, which compelled audible gasps of "woah." Set to music by Stravinsky, Balanchine plays with the musical composition's fractals, repetition, and sparkling invention, creating the ballet equivalent of witty repartee. Anthony Huxley more than holds his own, balancing Fairchild's sprinting flair with an equally engaged presence. Fairchild flew through the composition with the effervescence and pleasure of the champagne being served in the theatre lobby. The work is celebratory and refined, inventive but unselfconscious and Fairchild and Huxley execute it with daring confidence.

Featuring onstage pianist Elaine Chelton, the program's next work is the superficially similar 1975 Sonatine. Set to Ravel's three-part composition, Sonatine is a pas de deux which distinguishes itself by being simultaneously more aesthetically traditional than Duo Concertant and more choreographically iconoclastic. The look of the work, variations of metallic blue, makes it something of a lull compared to Duo Concertant. Ravels's hypnotic and soothing melodies are in themselves wafts of elegant blue, and this aesthetic repetition does drown complexity. Thankfully Gonzalo Garcia and Lauren Lovette do not overcorrect and execute the work's intended delicate sensitivity. This is no small feat as Sonatine features one of the more difficult Balanchine images to ground in dancerly elegance, an interlocked shared half backbend. While maintaining this shape, Lovette leads Garcia off stage left. It is a rare foray into the truly bizarre, in an otherwise reserved style.

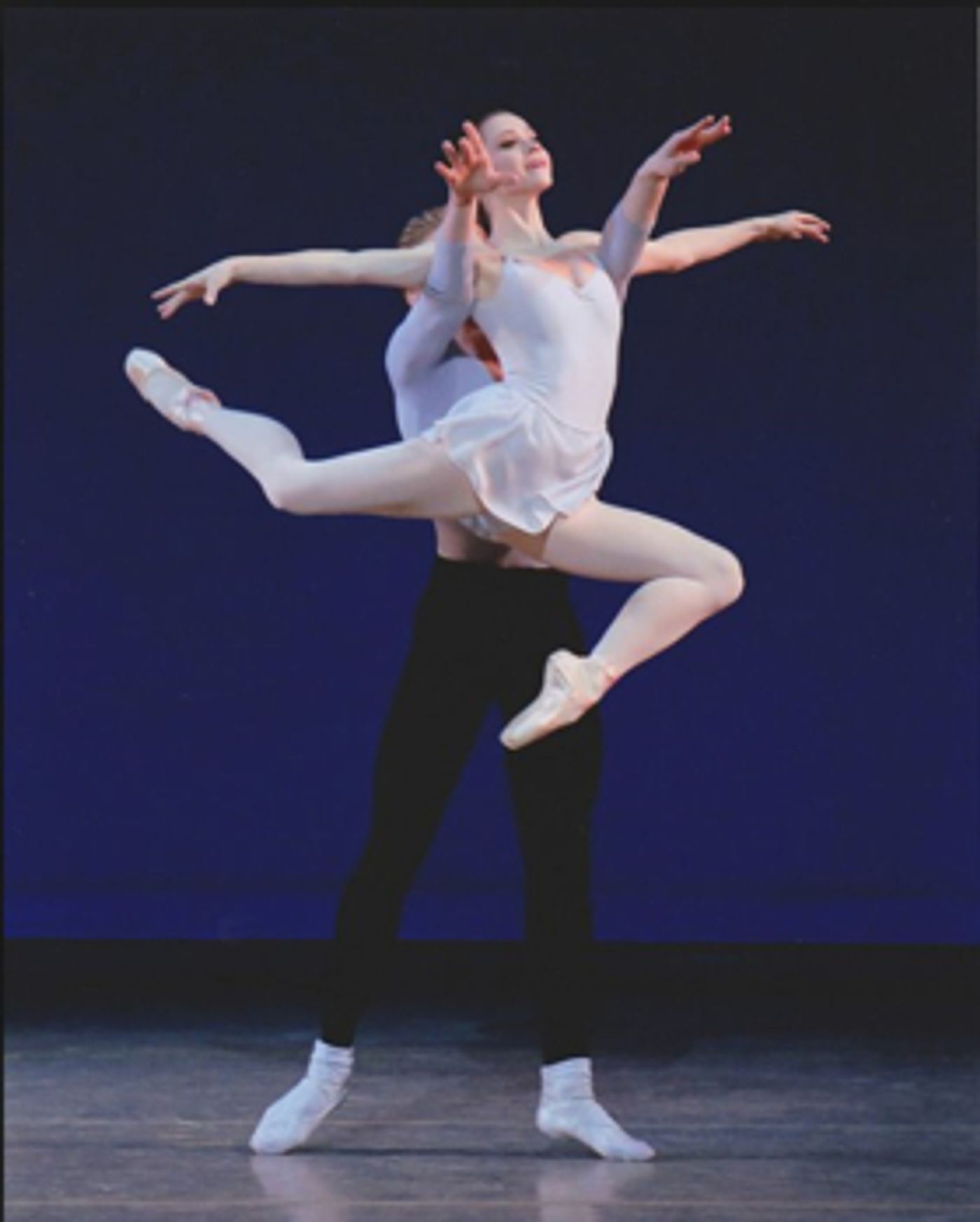

The evening's final work, 1972's sprawling Stravinsky Violin Concerto, is the epic landscape response to the two previous pas de deux. Stravinsky Violin Concerto is Balanchine's proof positive that ballet needn't just inspire, or awe, but can surprise. The shapes accomplished by the dancers are as confounding as you'll witness in a classical ballet company. Maria Kowroski and Adrian Danchig-Waring watch one another like trapeze artists as they execute pairings that seem on the outermost edge of experimentation in the Balanchine form. The following pas de deux, performed by Sterling Hyltin and Russell Janzen, runs more smoothly as it has a closer relationship with Stravinsky's music. Where Kowroski and Danchig-Waring fought for impossible shapes, Hyltin and Janzen offered a smooth shapely tangle. The work in its entirety is a loose tapestry of limbs, something between a Celtic knot and a cubist painting. Compositionally it's beautifully balanced, both too personal to be plastic and too modern to be intimate. Obsession with Balanchine can be deadly academic, or it can be a testament to a rare artistic heritage. This past Tuesday was a delightful look at the latter.

Reader Reviews

Videos