Review: THE WILD DUCK at Shakespeare Theatre Company

Top-flight production of great rarely-produced Ibsen work

The attention to detail in the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s terrific production of “The Wild Duck” extends to preshow atmospherics, with a distinct chill not attributable to the cooling autumn temperatures outside. Indeed, ushers walk the aisles before curtain time armed with blankets to distribute, in case anybody requests one. “The Norwegian cold,” one explains.

The Norwegian chill on stage comes from the personal interactions in one of Henrik Ibsen’s best plays.

It’s “very rarely performed,” director Simon Godwin said before the opening night performance. “This may be the first time you’ve seen it. It may be the only time you see it.”

All the more reason to redouble efforts to catch the first rate production at its Klein Theatre, which has already won over New York with a run at the Theatre for a New Audience in its run in September.

There’s no lack of Ibsen around, with productions of “A Doll’s House,” "Hedda Gabler” abounding and “An Enemy of the People” set to open next week at Theatre J.

“The Wild Duck” may be less produced because of its complexity. But in its adaptation by David Eldridge, the 1884 work crackles with power and contemporary relevance to issues of truth, self-delusion, class differences and corruption.

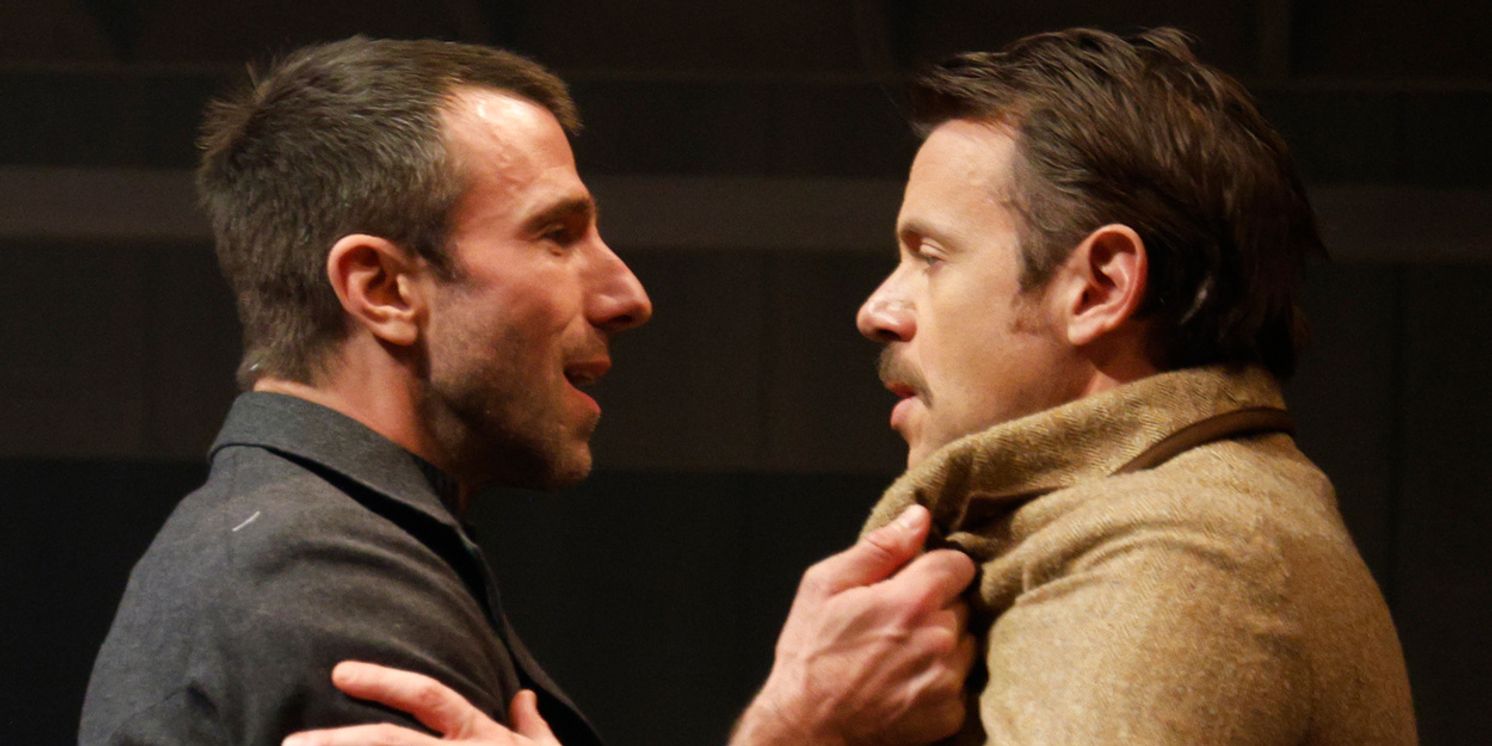

Essentially, it involves the reunion of two old chums, Gregers (Alexander Hurt), and Hjalmar (Nick Westrate) who learn of their respective families’ fates, mostly through the maneuvers of Gregers’ industrialist father (Robert Stanton).

Hjalmar’s own father — haggard, disheveled, ragged and worn — is reduced to menial jobs for the industrialist. He had taken the fall for some malfeasance of both men. But there are further insidious connections that are explored and expertly peeled in the production..

What might make for a lot of talky exposition is instead enlivened not only by Eldridge’s adaptation (that largely sticks to Ibsen but modernizes some phrases, such as the closing lines) but especially by the acting, under the direction of Godwin.

The nervous, naturalistic responses of Westrate (Victor Frankenstein in STC's acclaimed adaptation of the Shelley work) are brought nakedly to the stage, even against the assured air of "chronic righteousness" approach of the self-appointed truthteller played by Hurt, who brings that same perfectly self-satisfied hauteur commanded on screen over the years by his father, William Hurt.

And what a delight to see that haggard, white-haired grandfather scurry across stage — David Patrick Kelly of many David Lynch films (including the poor man who was informed by his appendage in “Twin Peaks,” “I am not your foot.”).

Stellar work is all around, though. Melanie Field makes an impression as the wife tryiing to keep her household together despite her husband's illusions (Field, who was strong in STC’s stellar “Uncle Vanya” last season, is also fondly recalled for her comic roles in TV series “Florida Girls” and “A League of Their Own”).

A revelation is Maaike Laanstra-Corn as their 15-year-old daughter, who is tremulous and declarative as circumstances occur that she can’t quite understand. She’s also encouraged to scream out as needed. Her character is the one who has kept the unseen wild duck in their loft, among rabbits and chickens in some kind of imagined forest. Though it is wounded, there is hope it will thrive.

That bird — like those that appear in Chekov and Strindberg, both influenced by Ibsen — is fraught with metaphor, of which there is no lack in this key work at the birth of modern theater. More than one character worries of blindness, two work in the relatively new field of photography though the overriding theme is that people are unable or unwilling to see what’s all around them.

Stanton makes his mark as the imperialist father, clad in a full length fur at one point (costumes by Heather C. Freedman); Mahira Kakkar brightens up the stage as a maid who knows exactly what she’s in for as his new fiancé. Matthew Saldivar, as a cynical doctor, gets the most laughs for his declarations — and there are laughs. This is the rare tragicomedy where Godwin threads just the right line between high hilarity and shattering truth.

Andrew Boyce’s set — a mansion hallway that makes way for the large, rambling photo studio and home — is subtly lit by Stacey Derosier through a large skylight that shifts from dusk to bleak dawns. Darron L. West’s sound design includes musical interludes from Alexander Sovronsky, performing Norwegian folk and classical music on solo viola an Norwegian Hardanger fiddle between set changes, at one point joined by multitalented Kelly on the long, Norwegian, dulcimer-like stringed instrument, the langeleik.

For all of its Norwegian roots, though, “The Wild Duck” still packs a universal power, and this production in particular hits all of its high notes.

Running time: Two hours and 30 minutes with one 15-minute intermission.

Photo credit: Alexander Hurt and Nick Westrate in “The Wild Duck.” Photo by Gerry Goodstein.

“The Wild Duck” runs through Nov. 16 at the Shakespeare Theatre Company Klein Theatre, 450 7th St. NW. Tickets available at 202-547-1122 or online.

Reader Reviews

Videos