Interview: Sheldon Epps of MY OWN DIRECTIONS: A BLACK MAN'S JOURNEY IN THE AMERICAN THEATRE Recounts the Highs & Lows of His Amazing Career

Epps' new memoir gives a fascinating and engrossing insight into his struggles and successes leading the Pasadena Playhouse and directing on Broadway and beyond

Given the necessary-if-belated conversations the American theatre community has been having over the past few years about how to overcome its longstanding dearth of leadership opportunities for people of color, it's fascinating to hear Sheldon Epps tell his own story as a Black theatre director who has been fighting those battles for quite some time - decades in fact. Epps enjoyed a remarkable 20-year tenure as Artistic Director of Pasadena Playhouse, bringing that venerable, overhwelmingly white institution (the training ground for such future luminaries as Dustin Hoffman and Gene Hackman) to new heights. He also conceived and directed the Tony-nominated musicals Play On! and Blues in the Night on Broadway. Along the way, he has worked with any number of legendary performers and Tony winners such as Diahann Carroll, Eartha Kitt, Beth Leavel, André De Shields, Debbie Gravitte, Tonya Pinkins and Leslie Uggams. As if that weren't enough, he has also directed over 150 episodes of some of the most iconic TV sitcoms of the past few decades, including Friends, Frasier and Girlfriends. Oh, and he recently directed the new holiday film, Christmas Party Crashers, which can be seen on BET+ starting November 17th.

Given the necessary-if-belated conversations the American theatre community has been having over the past few years about how to overcome its longstanding dearth of leadership opportunities for people of color, it's fascinating to hear Sheldon Epps tell his own story as a Black theatre director who has been fighting those battles for quite some time - decades in fact. Epps enjoyed a remarkable 20-year tenure as Artistic Director of Pasadena Playhouse, bringing that venerable, overhwelmingly white institution (the training ground for such future luminaries as Dustin Hoffman and Gene Hackman) to new heights. He also conceived and directed the Tony-nominated musicals Play On! and Blues in the Night on Broadway. Along the way, he has worked with any number of legendary performers and Tony winners such as Diahann Carroll, Eartha Kitt, Beth Leavel, André De Shields, Debbie Gravitte, Tonya Pinkins and Leslie Uggams. As if that weren't enough, he has also directed over 150 episodes of some of the most iconic TV sitcoms of the past few decades, including Friends, Frasier and Girlfriends. Oh, and he recently directed the new holiday film, Christmas Party Crashers, which can be seen on BET+ starting November 17th.

Epps' new memoir, My Own Directions: A Black Man's Journey in the American Theatre (McFarland Press, available on Amazon), recounts his rollercoaster ride of a life in the theatre, with the excitement and occasional anguish that accompanied the many highs and lows. His journey in the American theatre has been amplified by his experience as a Black man who has frequently been "one of the few," "the first" or even "the only." This is the very personal story of someone who wanted his race to be recognized, but never used it as a reason to be less than fully respected. In many ways, this memoir tells the story of what people of color in America must face repeatedly to make their lives matter.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Epps by phone from his home in Pasadena recently. He is a naturally engaging raconteur with a seemingly unlimited supply of fascinating tales to tell. Although he has been, as he puts it, "chased by race" his entire life, he has also succeeded against the odds as "just a boy from Compton." We talked about how he dealt with the racism, both covert and overt, directed at him during his tenure at Pasadena Playhouse, lessons he learned from mentors such as Garland Wright at the Guthrie and Jack O'Brien at The Old Globe, what it's like to suddenly find yourself in a room directing someone you've idolized since you were a kid, and what keeps him excited about working in the theatre. In conversation, he is warm and forthcoming, often punctuating his long, complex sentences with laughter. And throughout, there is his uncommonly resonant and expressive baritone speaking voice. The following has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What made you decide to write this book now?

Well, a couple of things. One was practical and the other sort of socio-political. When I stepped down from my position at Pasadena Playhouse in 2017, many people said to me, "Oh, you should write a book. Your experiences at the theater are so fascinating and I'm sure there's a lot that went into being one of the only Black artistic directors in America." Enough people say that and you start to think about it. But then I got busy doing other things and continuing to work in the theatre, which was a blessing.

Then we hit the pandemic, and suddenly we were all locked up and told not to leave the house, and so on a practical level that took away any excuse I had not to do it. Quickly following that, a number of big conversations started to happen about race and the American theatre connected to the Black Lives Matter movement, and I realized that many of those conversations sounded like conversations I'd been having for decades. The fact that those conversations were still going on, and actually still going on in the same way, was an additional motivator to say "OK, now is the time to tell this story." Because, unfortunately, it addresses so much of what we're still talking about and trying to overcome.

And as amazing as it is that we're now finally having those conversations on a broader level, I'm also old enough to know this is hardly the first time we've been talking about these issues -

Exactly!

- so it's interesting to hear the perspective of someone like you who's been having these conversations for a long time.

Yeah. I participated in one with Black Theatre United and Ten Chimneys Foundation which brought together their members and about 45 major theaters all over the country. When we'd get into the thick of those conversations, I would often say, "I know this is not the first time you're hearing this because I know you - sometimes specific individuals - have heard this from me over the last 20 years." So it was difficult and frustrating because we were often talking about it as if the subject had never come up. Or as if no one had ever thought about it or pointed out that things needed to change.

What was good is there was something about the politics surrounding that moment in time that gave these voices the courage to be raised more loudly and in greater numbers. And that they were suddenly coming from a lot of very well-known people with major Broadway and film and TV careers made it impossible for the field not to listen and not to make pledges to act, which in fact they have. Not that everything is solved, not that we don't have more work to do, but since that time a lot of things have changed and there are many Black and brown men and women running theaters now. There is no "one and only" anymore.

You really put Pasadena Playhouse on the map in so many ways despite battling with racism, sometimes subtle and sometimes not. In your book, you write "On reflection, I now think that I kept my personal reactions to the bigotry and the racism that I often faced at the theater well buried. I'm sure this was a defense mechanism that kept it from hurting too much." Can you talk a little more about that?

When you write a book, sometimes things emerge that you did not think about at the time you were going through them and that applies to that particular passage. I think it's true that in an effort just to move forward and, as I say in the book, keep my eyes on the prize, I did bury my personal feelings about some of those racial issues and things that were said, things that were done, things that were implied even if they weren't said, and just pressed on. I think if I had given myself too much to them emotionally, it might have battered me down or at the very least used strength and energy that I was putting into the work. Not to be grandiose about this, but in some ways I understand how Obama had to operate. You know what I mean?

Totally! To be honest, when I read that specific passage, it reminded me a lot of what I observed during Obama's presidency, that he often seemed hesitant to talk about racism, especially if it was directed specifically toward him rather than at somebody else.

Yes, that's exactly right.

Is it just harder to call out racism when you yourself are the target?

I think it's harder, and I think also if you talk about it on behalf of yourself it sort of lets the racists off the hook, if you know what I mean.

Can you expound on that?

Then they say (and they would have said this about Obama if he had been a different kind of temperament), "Oh, he's just a bitter, angry Black man." and they stop listening to what you're actually saying. So, yes, it is harder to talk about it when you're talking about racial stuff that is directed towards you as opposed to others. It's also hard to talk about it too often, because then you become the "race president," you become the "race artistic director." As opposed to what Obama wanted to be, which was President of the United States, doing all of the things that he had to do, and that he did. I wanted to be an artistic director who did all of the things that I wanted to do, and I did. I didn't want to be just about race.

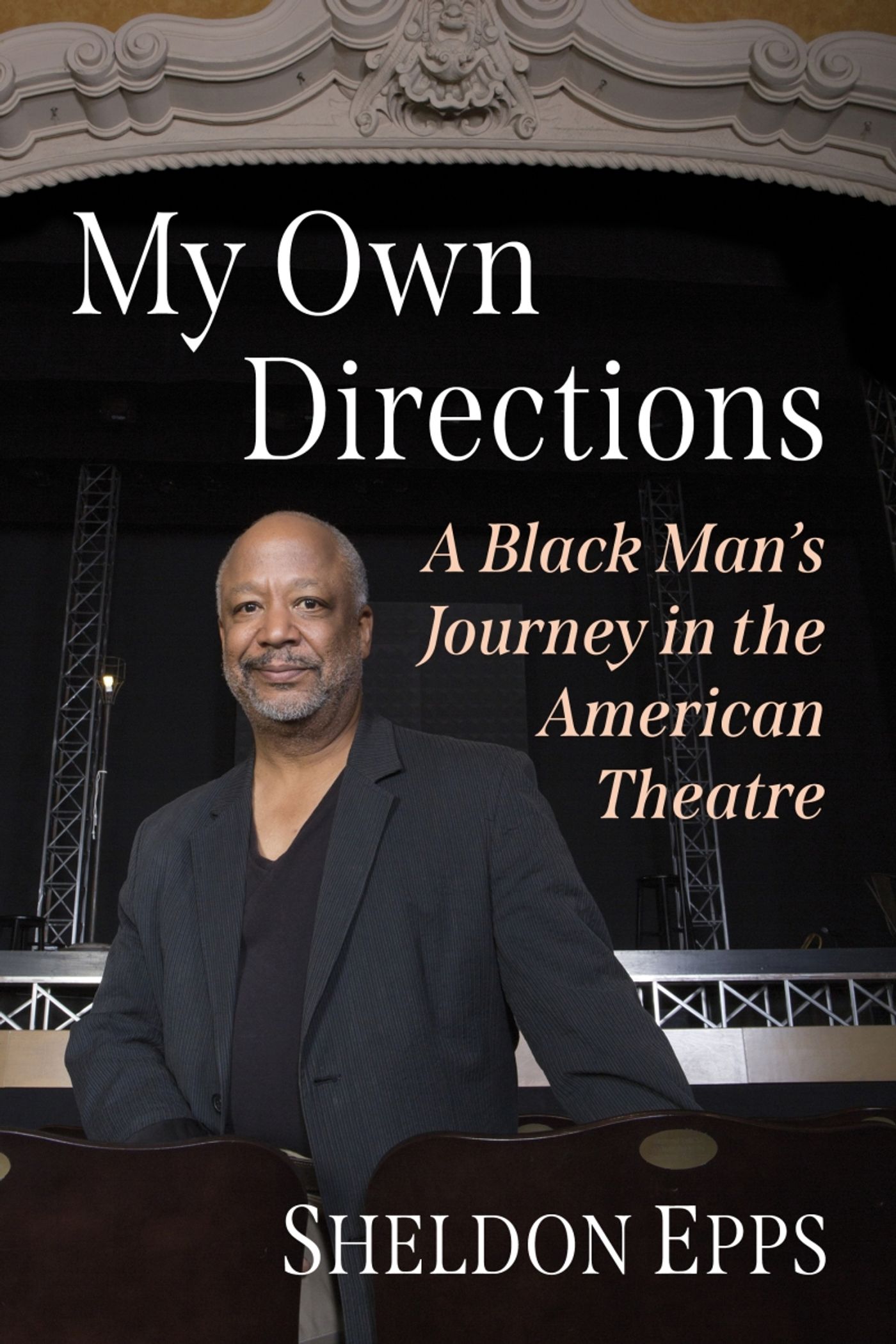

(photo by Jim Cox)

In the book, you mention how grateful you were for the time you spent "in the court of Garland Wright" at the Guthrie. You say one thing you learned from him about being a great artistic director was "staying out of the way until you are needed and then getting into the way (and knowing how to get in the way) when that is necessary. Also knowing that it is not always necessary." I think those two sentences perfectly sum up what is probably the most important thing of being an effective artistic director.

I agree. I started to learn that lesson in those conversations with Garland and continued to learn it with Jack O'Brien when I was at The Old Globe. It is not an artistic director's job to fix everything, or to try to be smarter than everybody else or have all the answers. It's really your job sometimes to just supply the questions and to encourage the other artists who are working in your theater to find the answers.

Sometimes it's your job to stay out of the way and be patient and give people time to find the answers. You know, anybody who goes to a first run-through of a show expecting it to be as complete and full as you hope it will be on opening night is crazy. So you shouldn't give those kind of notes to a guest director that you would not want to get as a guest director. [laughs] Those obvious things that with faith, trust and patience you know are going to be fixed, it's okay to leave those alone. But to ask the right questions is important, to let it be known when you were confused. And - simply to encourage is the most important thing you can do.

I would imagine that might be the hardest thing - to say, "OK, this element of the show clearly isn't working, but it's probably better if I just let them figure it out."

There have been many times, many productions, where in one way or another I asked the question, "What were you going for? What did you intend?" And being given the answer, sometimes my response is "Well, I did not get that." [laughs] I'm speaking now clearly as somebody who's walking in fresh, as an audience does. Or "I can see that you're intending that, but that's not clear yet, so trust your instinct about that and go further with it." Those kinds of conversations I think are much better than "You need to fix that!" Or "You need to let me fix that!" [laughs] You really should be there to help people fulfill their intentions and to be an outside eye to say, "This is very clear to me, and this is not so clear to me."

I loved your recounting of your first theatrical outing as a boy, which was to see the legendary Ethel Waters in The Member of the Wedding. I'm so envious you actually got to experience that because for theater nerds like me it's on that short list of performances that we would all kill to have seen.

Yeah, like Laurette Taylor in Glass Menagerie. [laughs]

Exactly! You write that "Somehow even with all the technique in the world in place, Miss Waters managed to add the elements of heart and humanity to her performance, which she shared with the audience in ways that were subtle yet gargantuan and ineffable." That's probably the best description I've ever read of what we mean when we talk about a true "star performance."

I think what I discovered that day was the power of a star performance on a stage. And by this time, she'd been doing it for years and probably had every single moment calibrated like a precision tool, you know? But you never saw that. All you saw was the tremendous humanity and heart and warmth and soul of this woman. Best exemplified by this amazing curtain call that she did, where suddenly everybody else disappeared and the curtain went up and she was sitting there in a rocking chair and looked up as if she was totally surprised that there was anybody out there looking at her. And you know she'd worked on that forever, right? [laughs] But you completely bought it. There was just something about her ability to take all of those years of technique and showmanship and "I know how to do this" and combine it with honesty and heart and soul. That is what you wish you would see from every star performer.

In the course of your career, you've been fortunate to work with a whole slew of big stars. As their director, how do you help them get to that exalted place? I mean, you know you're working with a star, but you also know you have to guide their performance, right?

It's a little bit of what I said about being an artistic director, sometimes you want to stay out of the way for a while. It's not a good idea working with a big star to walk into the first day of rehearsal and start ordering them around as if they don't know what they're doing. They do know what they're doing - that's why they're stars. [laughs] So you want to see what is the best of what they do in service to the play, the musical, whatever it is, and the character. Then you want to gently guide them into using only those well-honed things that are really appropriate for this particular play and this particular character.

You know, even big stars can be as insecure as an actor fresh out of university, so often it is about getting them to relax and believe that what they are doing is enough. They don't have to play every trick in their book. When you direct Eartha Kitt, you know you're directing someone who's got a lot of different tricks in her book, but she doesn't have to use every one of them all of the time. [laughs] Sometimes it's okay just to leave it alone, let it be. And when you can do that, then you get something like one of those Ethel Waters performances.

I also think it's important not to be overwhelmed by stardom, and actually Joan Plowright was a person who taught me that. There was a very shot-lived television show that she did a part in [Encore! Encore! also starring Nathan Lane], and on the first day of rehearsal, she said, "Please do not treat me like 'Dame Joan.' I'm just another actor." And I said, "Wow, that is a great piece of advice, Joan." [laughs] You sort of have to do that with big stars. You can't be overawed too much. You know, it's easy to fall under Diahann Carroll's spell.

Like how could you not?

Exactly! You do have to remind yourself, sort of on an hourly basis, "Yes, she's Diahann Carroll, but she's also a character in this play, so get Diahann Carroll to do what is right for the character in this play." Cause she'll charm you to death! [laughs]

You graduated from Carnegie Mellon and were well on the path to quite a successful career as an actor before you moved into directing and producing. Do you ever miss acting?

No, not all. Because early on when I started directing, I figured out that what was most fascinating to me was the putting it together, the figuring it out, the making it come to life in the rehearsal process. The repetition of it night to night was not all that interesting to me, and I became the kind of actor who had a lot of great technique but would sort of get through the run on that technique. In a way, I became the kind of actor I didn't like to watch very much, you know? One who was cheating, one who was there but not really there, every night. So I just knew it wasn't for me. Whatever it is that feeds actors in that way, doing a play over and over and over again, just didn't feed me. So, no, I don't miss that.

Acting taught me how to be a director, I think. Somebody once asked George Balanchine, "Could you ever be a great choreographer if you hadn't been a dancer?" and he laughed at the question. The interviewer asked, "Why are you laughing?" And he said, "Well, how would you know what to say?" And in some ways I think that's true of directors and acting. If I hadn't been an actor, at least if I hadn't studied acting - it gave me the tools to work with actors to know how to be helpful, what the language was. You learn other things about design and concept and all of that, but having been an actor certainly was one of the things that taught me to be a director.

Your book doesn't really cover your rather remarkable TV career directing over 150 episodes of so many hugely popular sitcoms. How did you manage to pull that off while working your day job at Pasadena Playhouse?

Very long days! [laughs] It was only possible because the theater is here in Pasadena, in greater LA, so literally I would spend a good portion of the day working on a television show like Frasier or Friends or Girlfriends, and at the end of that day come back to the theater and work in the office, and then see a rehearsal or preview or performance, and then spend my days off and weekends at the theater working.

I do now look back on it and wonder "How did I achieve that?!" Because now it seems a little bit insane. But it was, 1) the fact that I was at least in the same city so I could get to the theater every day at the end of the workday in television, and 2) the form of television that I did, half-hour situation comedy, for the most part didn't do 16-18 hour days. There was a portion of the day that was left once I finished that to come back and work at the theater. But it was hard and at some point the juggling got too intense, and that's why I put away working in television for a while.

Back in those years, I would see your name attached to Pasadena Playhouse and then I'd be watching Friends or Frasier or whatever and I'd see you credited as the director and I'd actually wonder if there were maybe two different guys named Sheldon Epps. [laughs]

Fortunately, not! [laughs]

Play On! is a show I've been really curious about for years even though I've never had the opportunity to actually see it. The combination of Shakespeare and Duke Ellington struck me as an intriguing concept, plus it had such an amazing cast led by André De Shields and Tonya Pinkins, and it generated terrific word of mouth in San Diego. I was sure it was going to be a big hit on Broadway, and then somehow it wasn't. In hindsight, do you wish you had approached the Broadway run any differently?

Oh, I'm sure I do. Interestingly, both of my kind of signature shows, Blues in the Night and Play On!, despite the fact they had Tony nominations and in the case of Blues in the Night an Olivier nomination in London, neither of them had great commercial success on Broadway. However, in both cases I got the opportunity to keep working on them post-Broadway, in the case of Blues in the Night over years and years.

With Play On!, initially it was getting to do it [post-Broadway] at the Goodman in Chicago that gave me an opportunity to approach it again and fix some things. And you know there were other things surrounding the short run on Broadway, economic things like marketing budgets and all of that. But one of the things may have been that we rushed going to Broadway a little bit too much and didn't have time to continue working on the show until post-Broadway. In every other theater where it's been done, it's been a very, very big hit and broken box office records.

That reminds me of when I saw Hamilton off-Broadway at the Public. It was already clear it was going to be a huge hit, and when the producers decided not to transfer it immediately in time for that Broadway season some people thought they were nuts. But they spent those extra few months really finetuning the show.

I think those creators were very smart about that, to say, "Listen, there's stuff we need to do to get it ready to go to Broadway." I think Play On! might have benefited from another regional production or workshop or something before we went to Broadway. In an odd way, the Broadway production became the workshop! [laughs]

I fear that happens all too often.

Yeah, and you know I was young and overly eager and perhaps too ambitious then. Now, I might insist on that. And have, in some cases, with other shows I'm doing now, where producers have been eager and say, "Let's just get to New York. Let's just go to Broadway." And I've said, "Well, I don't think we're quite ready for that. Let's see if we can find another out-of-town situation first."

When you're out of town, though, and audiences are already loving your show, is it hard to say, "No, we still have work to do."?

It's very hard, but as in the case with Hamilton, you've gotta be strict with yourself and know when that's the truth and abide by it. Have faith and patience that if it's this good now, it's only going to get better if you take more time to work on it. Very rarely - it's not impossible - but very rarely do things get worse because you give them more time and attention. [laughs] You've got to be very misguided for that to backfire on you.

I've only seen that happen with shows out of town that weren't very good to begin with. Often, the creative team ends up tinkering around the edges which ultimately just makes it even worse. But those shows were probably never going to work anyway.

Right, that's also something you've gotta know. When something is fundamentally flawed, for whatever reasons, you're not going to be able to beat it into being good. Sometimes you have to say, "Well, this is just an idea that doesn't quite work. So let's let this rest."

This may be impossible to answer, but out of the million and one plays and musicals you've worked on, which one feels most like your authentic self? Not necessarily which one was your favorite, but one that is the most honest reflection of how you see yourself in this world?

Wow, that is an impossible question! Well... I still think on the musical side Blues in the Night does that, because it's a combination of elements that are important to me theatrically and personally. And - my concept and production of 12 Angry Men did that. I'm a person who believes that whatever the problem is, if you go lock yourself in a room and talk about it openly and honestly, and/or argue about it and even fight about it, if you do that with an open heart and the right intentions, you can come to a better place. And both in the original and in my concept of the play, that's exactly what those guys had to do.

What was your concept for 12 Angry Men?

Well, interestingly, it was Obama-related again. It grew out of that moment with the Trayvon Martin case where Obama did in fact finally come forward and talk about racial issues, about the fact that young man could have been his son, or could have been him at a younger age. He was incredibly open and honest about it in a very heartfelt way.

And I said, "Okay, if he's brave enough to address this head-on like that, then I need to do something at the theater that addresses it in the same way." In one of those lightbulb moments that we sometimes luckily get, I said, "I'm going to do 12 Angry Men with six Black men and six white men, and try to discover what that does to the play without rewriting it at all."

What it did to the play was flabbergasting and overwhelming. It gave so much of the play a richness of subtext, which was perhaps already there to a certain degree, but resonated in a whole different way. There's a moment in the play when the vote is taken and the next character's line is "Huh... six to six. Whaddya think of that?" Well, when that vote is six Black men and six white men, that line suddenly has a tension and a combustibility that is amazing. And when you see the triumph of everybody coming around to doing the right thing by the end of the play, because they've faced not only the case and their prejudices about the case, but their prejudices about the other people in the room, it's just incredibly moving.

That line you just quoted, if you didn't already know the play you would probably think "Oh, they just added that in for this production."

That's exactly right. And people did that, you know people constantly said, "Well, that line, you put that line in, right?" [laughs]

Since you don't appear to be retiring anytime soon, are there any plays you haven't gotten to direct yet that you'd really still love to have a go at?

This probably sounds like a really hubristic or arrogant answer, but...

Go for it!

- no. And it's just the good fortune of my life and the way it's occurred. Most directors have that shelf of plays on their wish list, but I guess because of my time at The Old Globe for four years where I got to choose many of the things I wanted to do and then 20 years of programming at Pasadena Playhouse, I've really taken all of those play off the shelf. I've gone through all of the plays I really wanted to do, that were really calling to me, and even all the styles of plays, which I realize I'm incredibly blessed and fortunate to have done.

So now I'm waiting for that thing to come along and be presented to me that gets my juices going. And fortunately, that has happened. I just did a play [by Martin Casella] called Miss Maude in Houston, Texas. And I did a new play [Deborah Brevoort's My Lord, What a Night] about the relationship between Albert Einstein and Marian Anderson at Ford's Theatre. So, yeah - I can't think of things that I'm longing to do that already exist. I'm really waiting for that new thing that has a great story or great situation or great characters to be put in front of me, that makes me leap up and say, "Okay, this is one I've gotta do!"

Videos