Feature: Stephen's Sondheim (or How a Stranger Informed Five Decades of One Life)

In 2021 the world said goodbye to Stephen Sondheim. This is how he lives on for one writer.

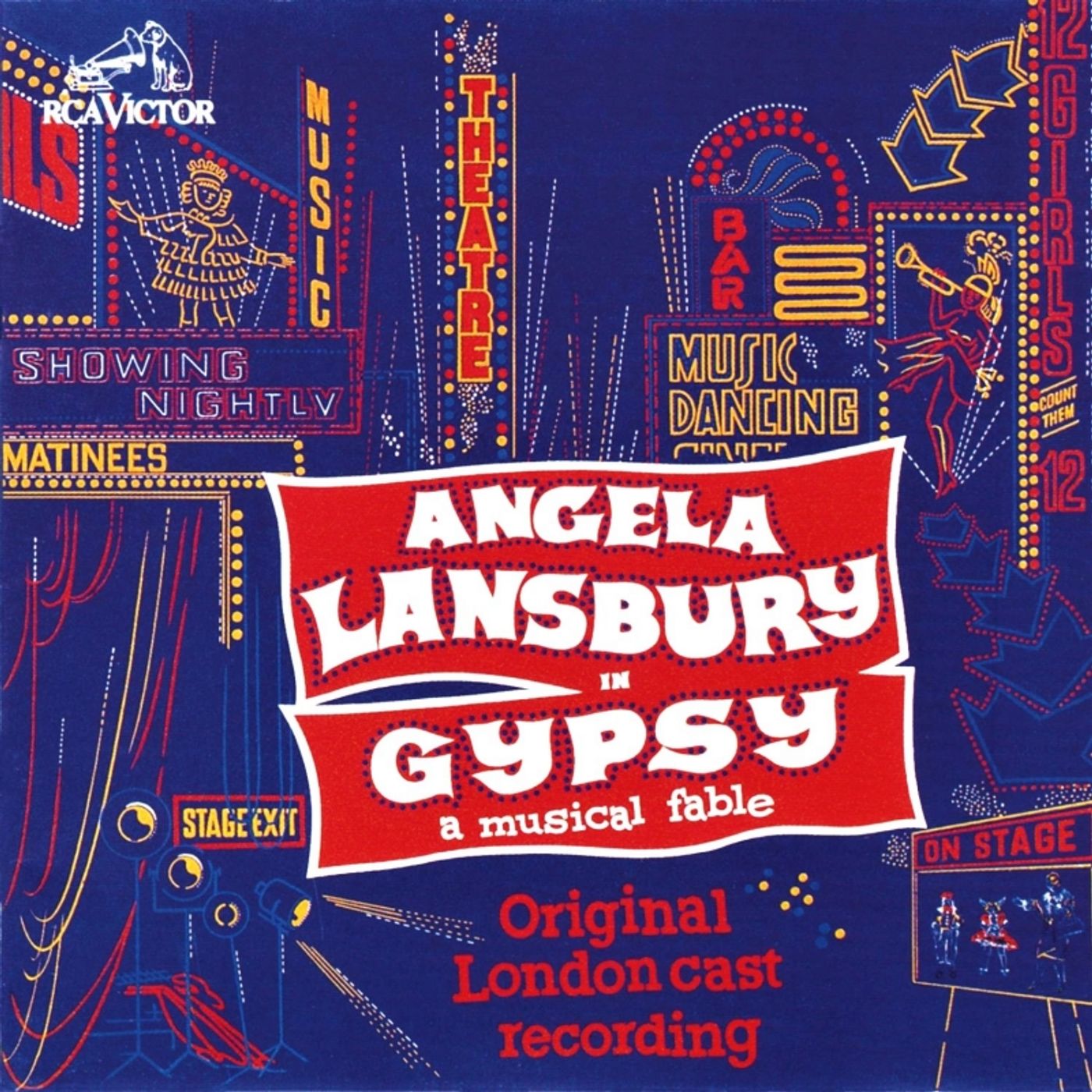

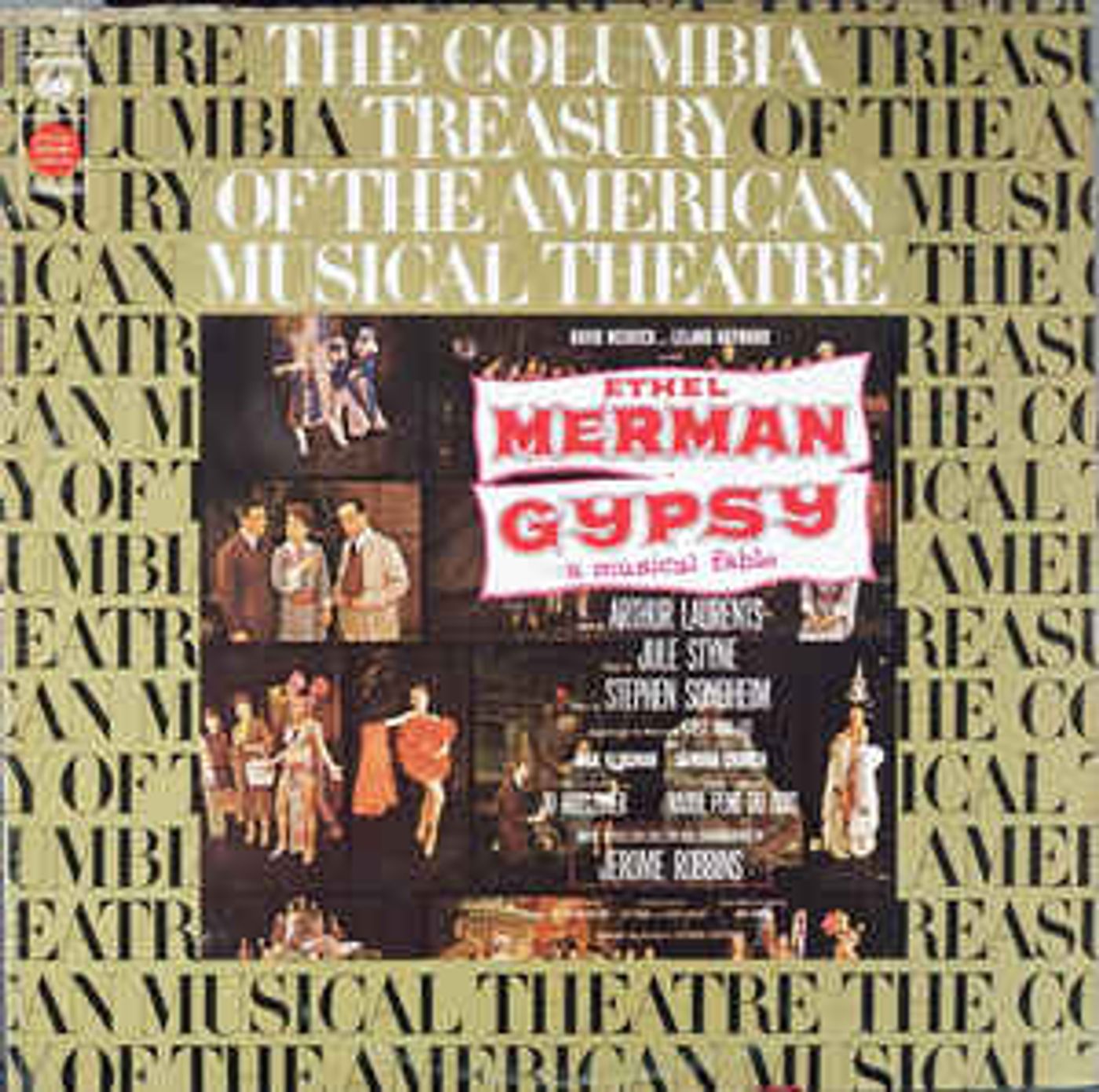

I was eleven years old, maybe twelve, but no more than that. I was with my mother at the department store, probably Sears Roebuck, definitely not K-Mart - I remember the decor of the shop and, in my mind, it looks like Sears. Whenever we were in a store like this, my Mam would allow me to do my own thing, which usually amounted to me hanging around the record department, flipping through the albums, usually Broadway cast recordings or movie musical soundtracks. On this day, I spotted a name that I knew, a name that I loved, and I snatched up the vinyl product bearing that name and carried it over to Mama, waiting in line to return something, there to beg her to buy me the recording, which she flatly refused to do.

"But look, Mommy, it's Angela Lansbury. From Bedknobs and Broomsticks. Can I PLEASE have it?"

"But look, Mommy, it's Angela Lansbury. From Bedknobs and Broomsticks. Can I PLEASE have it?"

"No sweetheart," said Mommy, explaining, "That musical is about strippers and you're too young for it."

My Mother (widely considered by all to be the coolest mom on the block, even to this day) would hear none of my pleading, none of my insistent urgings, none of my promises that I was, indeed, old enough to have the record album upon which was emblazoned the name of the woman who had been my idol since the age of eight.

"No son of mine is going to have a record album from a musical about strippers. You'll have to wait until you're older."

The conversation was over.

I did, in fact, not own any cast recording of GYPSY until I was in college, when a record-buying spree the summer before I started my freshman year sent me to Texas with a suitcase full of albums bought at Footlight Records in New York City. Among that stack of albums were Lena Horne: The Lady And Her Music Live On Broadway, Sophisticated Ladies, both the Lansbury and Merman recordings of Gypsy, and two musical cast recordings about which I knew nothing named Follies and Merrily We Roll Along. I had seen Alexis Smith sing a sentence or two of a song from Follies on the Night of a Thousand Stars, and I had heard Carly Simon sing a song called "Not A Day Goes By" on her album titled TORCH. I wanted to educate myself about musical theater, so I bought the albums (and more) and settled in at college, where I listened to those Sondheim records non-stop for one year straight. Well, more than that.

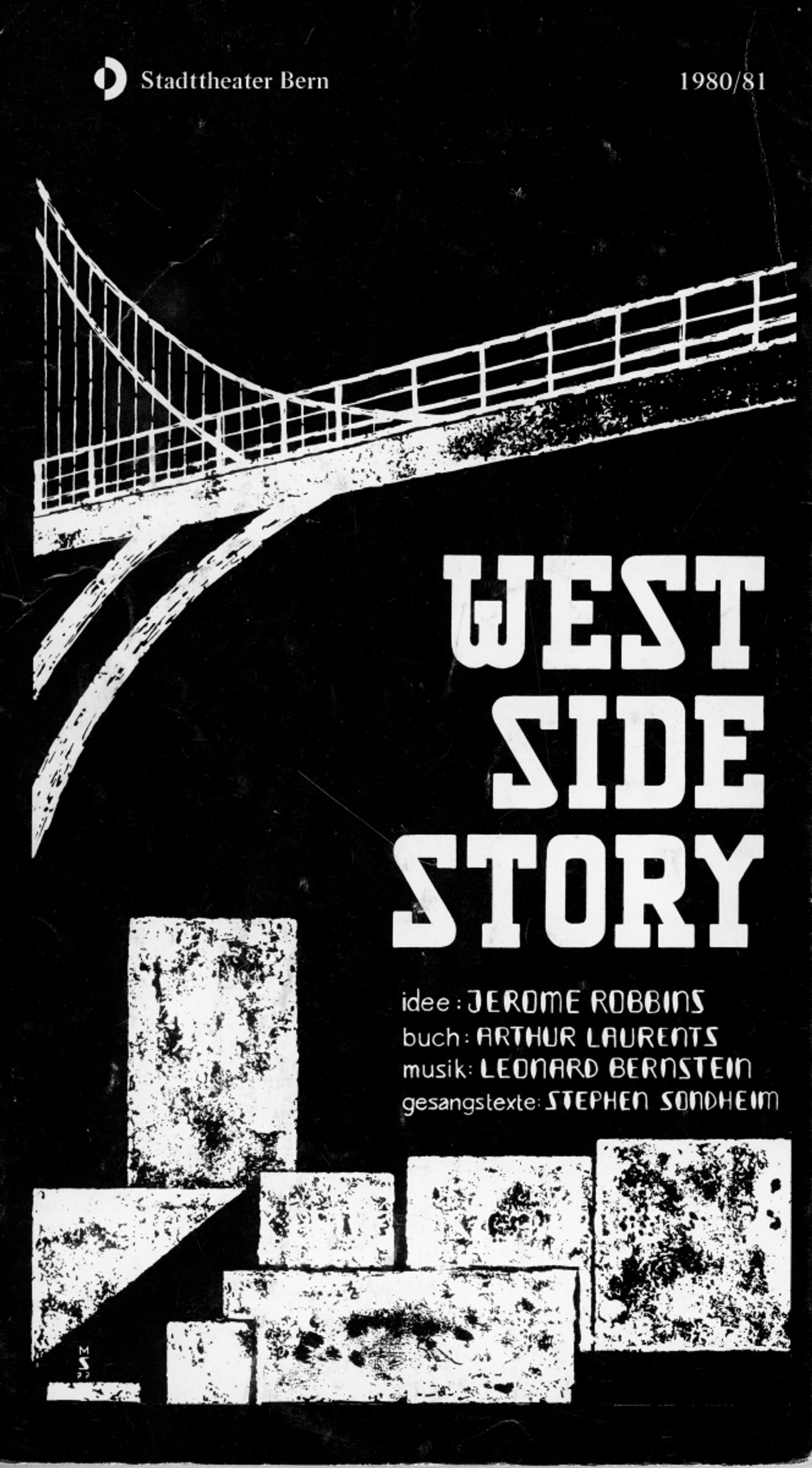

I didn't know who Stephen Sondheim was, even when he was already an active part of my life. I had become obsessed with West Side Story when I was in High School because the Stadttheater Bern had a thing for producing Broadway musicals (always translated into German); the people of Switzerland just loved American musicals but always in German, never in English. When I saw the play, I spoke enough German to follow what was happening, but after seeing the show, I borrowed the soundtrack from a friend's parents, made a copy by holding my cassette player up to the stereo speaker to record it, and I nearly drove my poor mother mad with repeated listenings to singers who, years later, I would learn were not the actors who actually appeared in the movie. My best friends were a pair of brothers, Karl and Ian Thompson, who finally had to smack me down for continually singing, "Anita's gonna get her kicks toniiiiight..." So obsessed was I with West Side Story that I manifested the meeting of the members of the cast of the play, many of whom were American actors living and working in Switzerland. One of them would go on to play Raoul in the original production of Phantom of the Opera, a man named Steve Barton who played Riff in that first production of West Side Story. To this day, I can remember the German translation:

I didn't know who Stephen Sondheim was, even when he was already an active part of my life. I had become obsessed with West Side Story when I was in High School because the Stadttheater Bern had a thing for producing Broadway musicals (always translated into German); the people of Switzerland just loved American musicals but always in German, never in English. When I saw the play, I spoke enough German to follow what was happening, but after seeing the show, I borrowed the soundtrack from a friend's parents, made a copy by holding my cassette player up to the stereo speaker to record it, and I nearly drove my poor mother mad with repeated listenings to singers who, years later, I would learn were not the actors who actually appeared in the movie. My best friends were a pair of brothers, Karl and Ian Thompson, who finally had to smack me down for continually singing, "Anita's gonna get her kicks toniiiiight..." So obsessed was I with West Side Story that I manifested the meeting of the members of the cast of the play, many of whom were American actors living and working in Switzerland. One of them would go on to play Raoul in the original production of Phantom of the Opera, a man named Steve Barton who played Riff in that first production of West Side Story. To this day, I can remember the German translation:

"Ich hab' es gern in Amerika, alles ist schön in Amerika"

And the greatest English to German translation of all time:

"Boy, boy, crazy boy, bleib kühl boy."

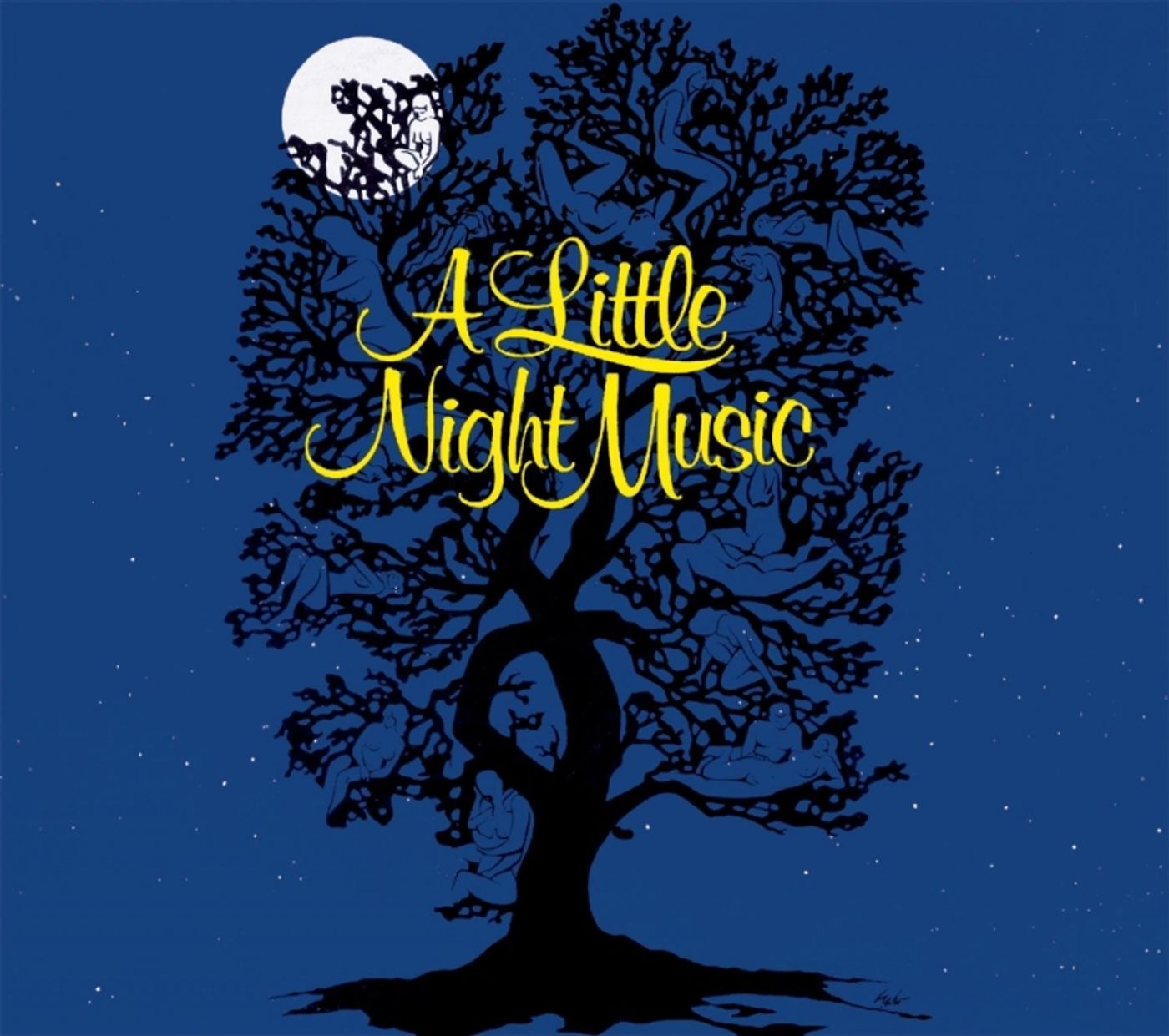

And even though I was the world's worst singer, I insisted on singing "Maria" in the annual talent show at the International School of Berne, and when Steve came to see me sing and dance (to a number from Pippin) in the revue, all he would say afterward was, "Boy! Can you dance!" His insistence on not remarking on the singing was not a subtle message, even to a seventeen-year-old. To his credit, when I showed even the slightest interest, Steve gave me the name and number of a voice teacher, an opera singer who worked at Stadttheater Bern who vocalized me on scales, immediately thereafter declaring that I should learn to sing with the song "Send in the Clowns" because it wasn't very rangy, and neither was I. The boisterous Italian who would, time to time, cry out "eccola!" sent me to a music shop where I was able to buy a music book from the play A Little Night Music. I was scandalized. The illustration on the cover of the book was terribly suggestive, and I was more than a little sheltered, more than a littel shy, more than a little prudish; I had no idea what this play was about, but I could tell from that drawing that it wasn't my kind of show, especially after reading the lyrics to the song titled "The Miller's Son." Scandalous. A high-falutin' intellectual, though, I did rather like the lyrics to a song called "Liaisons," even though I didn't know what that word meant or, for that matter, what the song was about. I urged my voice teacher to let me work on that composition instead of the clown number, so he played it through for me, singing the words that I didn't understand. Never mind, said I, I don't like that melody, said I, it's not very pretty, said I, I'll stick with the clown song, said I.

cover of the book was terribly suggestive, and I was more than a little sheltered, more than a littel shy, more than a little prudish; I had no idea what this play was about, but I could tell from that drawing that it wasn't my kind of show, especially after reading the lyrics to the song titled "The Miller's Son." Scandalous. A high-falutin' intellectual, though, I did rather like the lyrics to a song called "Liaisons," even though I didn't know what that word meant or, for that matter, what the song was about. I urged my voice teacher to let me work on that composition instead of the clown number, so he played it through for me, singing the words that I didn't understand. Never mind, said I, I don't like that melody, said I, it's not very pretty, said I, I'll stick with the clown song, said I.

That freshman year of college changed all that. My drama teacher and head of the Drama Department, Stacy Schronk, gave me the musical theater education I had not been able to get at private schools in Portugal and Switzerland. He praised, at length, Stephen Sondheim, declaring Follies to be his personal favorite, and I spent the years of 1982 through 1985 immersed in the records that would teach me that musical theater had changed since I discovered it at the age of eight by checking out cast albums for Oliver! My Fair Lady, Hello, Dolly! and Funny Girl at the local library. I was swimming in Sondheim, determined to learn every word of every song in every musical he had ever created. The Footlight Records-acquired Merrily We Roll Along became my youthful obsession because I believed, to the deepest place of my being, that I would be a Franklin Shepard or a Charley Kringas, working in show business and making art, and to this day when I listen to the song, "Our Time" I do so with hot, stinging tears pouring down my face, for whatever personal reasons there are that go deeper than they probably should. That all-important first year of college, when I was learning to be an adult, when every emotion was so big, every stake was so high that the music played became like fibers in the muscles of my body, set a standard for the decades that would follow. Even now, the starting violins of the original recording of "Losing My Mind" or the opening chords of Elaine Stritch's "The Ladies Who Lunch" inspire, within, the rising up of all of the earth-shattering emotions

That freshman year of college changed all that. My drama teacher and head of the Drama Department, Stacy Schronk, gave me the musical theater education I had not been able to get at private schools in Portugal and Switzerland. He praised, at length, Stephen Sondheim, declaring Follies to be his personal favorite, and I spent the years of 1982 through 1985 immersed in the records that would teach me that musical theater had changed since I discovered it at the age of eight by checking out cast albums for Oliver! My Fair Lady, Hello, Dolly! and Funny Girl at the local library. I was swimming in Sondheim, determined to learn every word of every song in every musical he had ever created. The Footlight Records-acquired Merrily We Roll Along became my youthful obsession because I believed, to the deepest place of my being, that I would be a Franklin Shepard or a Charley Kringas, working in show business and making art, and to this day when I listen to the song, "Our Time" I do so with hot, stinging tears pouring down my face, for whatever personal reasons there are that go deeper than they probably should. That all-important first year of college, when I was learning to be an adult, when every emotion was so big, every stake was so high that the music played became like fibers in the muscles of my body, set a standard for the decades that would follow. Even now, the starting violins of the original recording of "Losing My Mind" or the opening chords of Elaine Stritch's "The Ladies Who Lunch" inspire, within, the rising up of all of the earth-shattering emotions  only experienced by an eighteen-year-old. I remember the time I was acting in a college play, a comedy by Anouilh, with a cast of actors who diminished me, making it impossible to get up the energy to be funny; before every performance I took my Broadway cast recording of Gypsy to the stage manager's desk, put the disc on the high-fi, plugged in my headphones and listened to "Everything's Coming Up Roses" until I had forged the energy to feel funny. There was the Christmas when my neighbor Carolyn Freeman and I were both stuck in Denton, unable to get home, spending every day together watching a videotape of the PBS screening of Sweeney Todd, or listening to the cast album, singing at full voice because the rest of the neighbors in the apartment complex were all gone for the holidays. The subsequent PBS screenings of the Follies concert, Sunday in the Park With George, and the NYC Opera A Little Night Music became regular viewings in our home. I finally understood A Little Night Music, and Sunday in the Park With George had, immediately, become my favorite musical, from the very first PBS viewing, informed by the legendary Act One finale, as performed on the Tony Awards, that left me hyperventalating and sobbing. And, of course, there was "Into The Woods"

only experienced by an eighteen-year-old. I remember the time I was acting in a college play, a comedy by Anouilh, with a cast of actors who diminished me, making it impossible to get up the energy to be funny; before every performance I took my Broadway cast recording of Gypsy to the stage manager's desk, put the disc on the high-fi, plugged in my headphones and listened to "Everything's Coming Up Roses" until I had forged the energy to feel funny. There was the Christmas when my neighbor Carolyn Freeman and I were both stuck in Denton, unable to get home, spending every day together watching a videotape of the PBS screening of Sweeney Todd, or listening to the cast album, singing at full voice because the rest of the neighbors in the apartment complex were all gone for the holidays. The subsequent PBS screenings of the Follies concert, Sunday in the Park With George, and the NYC Opera A Little Night Music became regular viewings in our home. I finally understood A Little Night Music, and Sunday in the Park With George had, immediately, become my favorite musical, from the very first PBS viewing, informed by the legendary Act One finale, as performed on the Tony Awards, that left me hyperventalating and sobbing. And, of course, there was "Into The Woods"

Not only did our family see the PBS Into The Woods over and over and over oh VHS, we saw it from the second row.

In 1988 my boyfriend (these days, my husband) and I flew to New York to see Steve Barton in Phantom of the Opera, the week before the Tony Awards. In anticipation of our week of theatergoing, we bought tickets to a few other shows, including Carrie and Into the Woods. The day we arrived in Manhattan Carrie closed, and on our second day we saw the fractured fairy tales show, sitting on the aisle of the second row, house left. Knowing nothing about the play, we were there to experience it in real-time. Needless to say, we were overwhelmed by the magic and the majesty and, especially, by Joanna Gleason, who we met at the stage door, after, and who we assured, enthusiastically, "You're going to win the Tony!" When that PBS screening aired, we were transported back to the Martin Beck, again and again, every day for a month: it was heaven on a videotape. When, in 1993, I was the victim of a drive-by shooting and rushed to Parkland Memorial Hospital, my boyfriend (the same one that became my husband) was brought back to the emergency room to sit with me, shaken and teary-eyed, as the doctors examined my leg and gave me a tetanus shot, right smack dab into the bullet hole, and, in order to keep me calm during the process, Pat held my hands with his, looked me in the eyes, and sang:

"Oh, if life were made of moments, even now and then a bad one, but if life were only moments, then you'd never know you had one...."

All the way to the end of the song.

"Moments in the Woods" would become the song that we sang to each other, throughout our life together, any time something significant, scary, or splendid happened. Indeed, on an occasion in the new century, during a party in our Midtown Manhattan home, a guest of the festivities said to me, "Let's go into your office and smoke some weed." I told him I can't smoke marijuana, it makes me sick. Urging me that this was "really good sh*t" that would not make me sick, my friend encouraged me to just do one tiny hit. Naturally enough, I got sick, was rendered unable to host my own party, and had to confess to my guests why I was just going to sit on the sofa until I could stand on two feet, once more. After a while, Pat came to me, sat down in front of me, took my hands in his and sang:

"Oh, if life were made of moments, even now and then a bad one, but if life were only moments, then you'd never know you had one...."

All the way to the end of the song.

A guest seated on the sofa nearby stood up, declared it to be the most beautiful thing he had ever seen, and went to the bathroom for a bit of a weep.

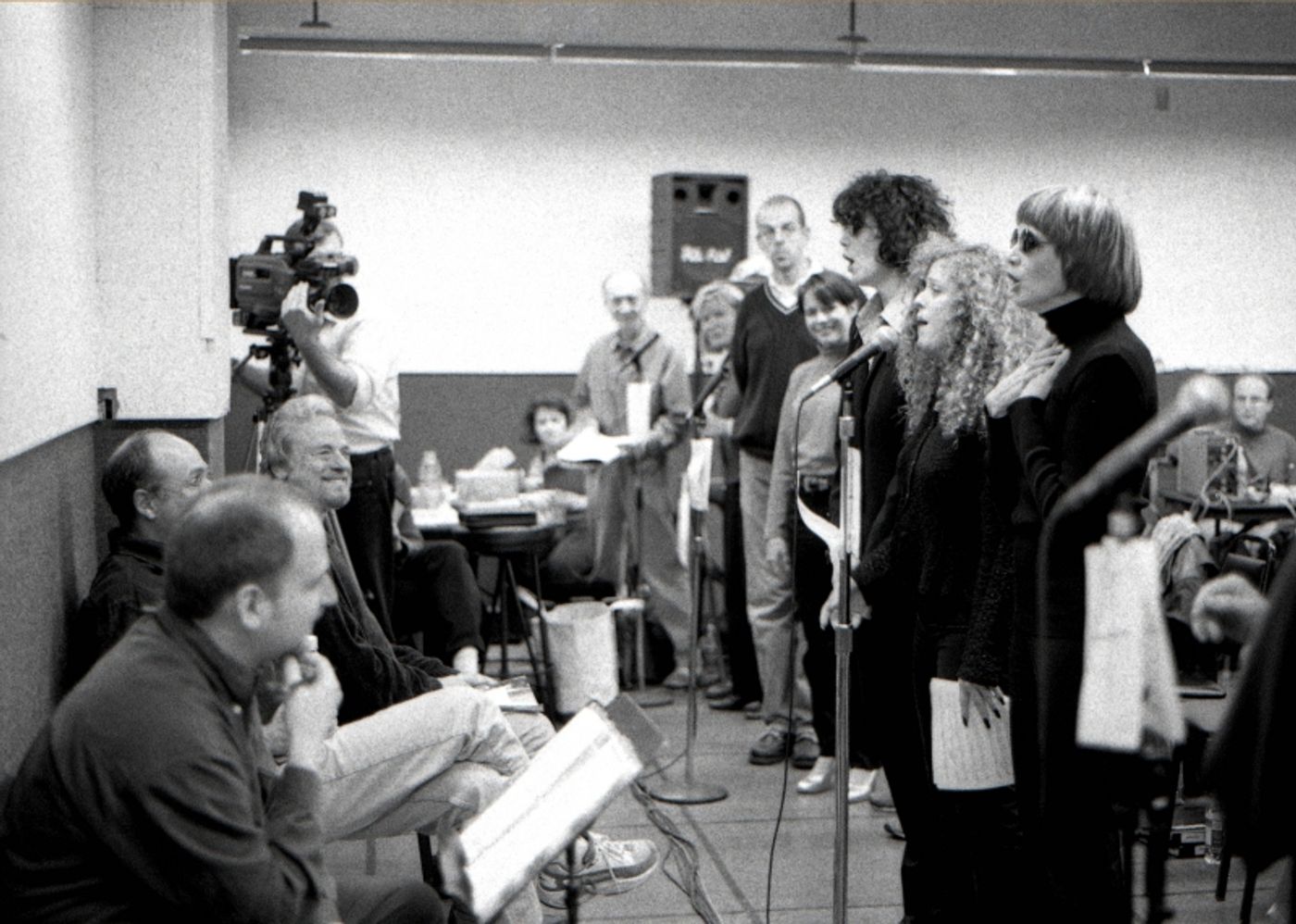

I moved to New York City to be a photographer. I had an idea for a book, a photographic study involving many different models and a sweater. It was called The Sweater Book. It took years to get off the ground and, while I was working on getting it to take off, I looked for other photographic work. My first big gig in the city came by way of the publicist Michael Borowski, who asked me if I thought I could photograph a live performance on Broadway. I said yes, of course, and he gave me the job. My pictures of the Sunday In The Park with George concert were published everywhere. Years later, Michael would call again, asking me to photograph a few minutes of a rehearsal for the upcoming Into The Woods concert, as well as both performances. The day of the rehearsal, I arrived at the (quite full) rehearsal hall, wordlessly tiptoed in, shot a few photos, and then fled. It was not for me to get in the hair of the artists by .jpg?format=auto&width=1400) being distracting; once I had what was needed, it was best to bounce. The day of the performances, I was given carte blanche to do as I needed, moving about the Broadway Theater and capturing both performances of the magical day on several rolls of film. A few years later, reading that there was to be a reunion concert of Passion, I sought out publicist, producer, or anybody else that might listen and might say yes, and, using the previous two concerts as a resume, I pushed my way into the event. It was not quite the experience for which I had hoped - my time there was cut, unceremoniously, short by an irate creative on the production, but it did allow me to capture, on film, a few pictures of the occasion, notably some important shots of female leads Marin Mazzie and Donna Murphy, the latter of whom had been a good friend for a few years, a friend I met during the original run of Passion who grew to be one of my dearest, a friend with whom I would share many memorable moments over the years. Documenting the occasion for her was one of the proud moments of my life behind the camera. It was the Into The Woods concert event that would bring Joanna Gleason into my life, as well, years after the fact.

being distracting; once I had what was needed, it was best to bounce. The day of the performances, I was given carte blanche to do as I needed, moving about the Broadway Theater and capturing both performances of the magical day on several rolls of film. A few years later, reading that there was to be a reunion concert of Passion, I sought out publicist, producer, or anybody else that might listen and might say yes, and, using the previous two concerts as a resume, I pushed my way into the event. It was not quite the experience for which I had hoped - my time there was cut, unceremoniously, short by an irate creative on the production, but it did allow me to capture, on film, a few pictures of the occasion, notably some important shots of female leads Marin Mazzie and Donna Murphy, the latter of whom had been a good friend for a few years, a friend I met during the original run of Passion who grew to be one of my dearest, a friend with whom I would share many memorable moments over the years. Documenting the occasion for her was one of the proud moments of my life behind the camera. It was the Into The Woods concert event that would bring Joanna Gleason into my life, as well, years after the fact.

During the run of Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, I printed up some photos from the Into The Woods concert and put them into a photo album, which I sent to the Leading Lady at the theater. The thank-you email that Joanna wrote to me led to a friendship that has lasted, lo, these many years, years during which Joanna has acted as more than a friend but served as a philosophical .jpg?format=auto&width=1400) teacher and life mentor, and, indeed, ring-bearer at my first wedding to Pat Dwyer, who had stood beside me, years earlier, at the stage door of the Martin Beck, insisting that "You're going to win the Tony!" There, in a public garden in Connecticut, as Pat and I exchanged rings and vows before our friends Marci Reid, Hunter Gilmore, and Joanna Gleason, we turned to each other and we sang:

teacher and life mentor, and, indeed, ring-bearer at my first wedding to Pat Dwyer, who had stood beside me, years earlier, at the stage door of the Martin Beck, insisting that "You're going to win the Tony!" There, in a public garden in Connecticut, as Pat and I exchanged rings and vows before our friends Marci Reid, Hunter Gilmore, and Joanna Gleason, we turned to each other and we sang:

"Oh, if life were made of moments, even now and then a bad one, but if life were only moments, then you'd never know you had one...."

All the way to the end of the song.

.jpg?format=auto&width=1400)

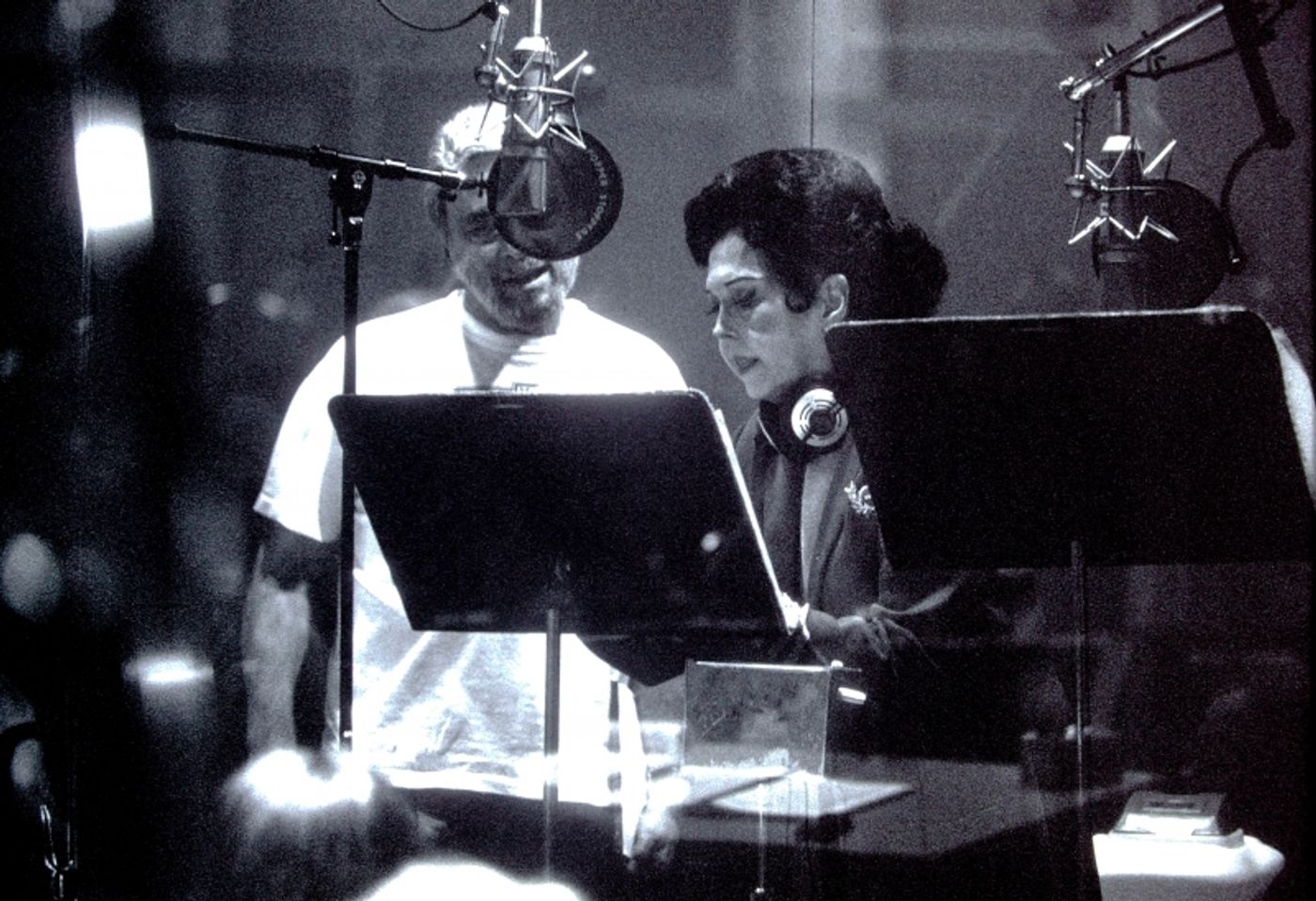

I met Stephen Sondheim. Twice. The first time, I was contracted to photograph the recording sessions for the Paper Mill Follies. It would be three days of work, and I was happy (no, I was thrilled) to do it. On the first day there, I was urgently advised to not speak to Mr. Sondheim, to stay away from Mr. Sondheim, to only speak to Mr. Sondheim if Mr. Sondheim spoke to me first. I did just that, for the most part, as the gentleman and I shared a proximity in the control booth that was justthisclose to one another, as I hovered in the background of the recording studio, surreptitiously snapping shots that would document the event, and as I shared that room with only Meredith Patterson, Michael Gruber, Paul Gemignani, and Mr. Sondheim, there to .jpg?format=auto&width=1400) rehearse and record the "Who Could Be Blue/Little White House" duet. Hiding behind a music stand in the corner, I watched through a lens as this man, so revered by all, this man whose artistry had, so, touched my life, talked two beautiful young actors through their upcoming task of preserving, for the first-ever complete recording of a legendary score, one of the expurgated original songs. All of the artists were so intent on capturing the moment correctly, the conversation was so detailed and yet casual, caring yet concentrated - it was a fly-on-the-wall moment unlike any other. And to be there, in the room, to hear the song sung live, in real-time was an honor unmatched. After the completion of their task, all turned to vacate the room, with Mr. Sondheim trailing behind the others.

rehearse and record the "Who Could Be Blue/Little White House" duet. Hiding behind a music stand in the corner, I watched through a lens as this man, so revered by all, this man whose artistry had, so, touched my life, talked two beautiful young actors through their upcoming task of preserving, for the first-ever complete recording of a legendary score, one of the expurgated original songs. All of the artists were so intent on capturing the moment correctly, the conversation was so detailed and yet casual, caring yet concentrated - it was a fly-on-the-wall moment unlike any other. And to be there, in the room, to hear the song sung live, in real-time was an honor unmatched. After the completion of their task, all turned to vacate the room, with Mr. Sondheim trailing behind the others.

"That's one of my favorites," I muttered to the legend in a t-shirt. He turned to me with a slightly surprised look on his face.

"Really? It's just my Jerome Kern imitation."

"There's nothing about you that is imitation." It just came out of my mouth, as I wound the film back into the canister, like an exhale of air. And he laughed and smiled. Then Stephen Sondheim walked, wordlessly, away.

The photos were never used. The brilliant illustrator Hilary Knight was contracted to sketch the artists, and the CD booklet presentation was breathtaking, one of the best I've ever seen, with Mr. Knight's artistry taking the packaging to levels otherwise impossible. I don't mind that nobody saw the photos, I'm just proud to have been there to make them.

The second opportunity I had to talk to Stephen Sondheim was no more than a moment in time. By some miracle, I was invited to the closing night party of the 2001 revival of Follies. My husband (a most generous and gracious man) agreed that he should skip the party so that I could take our friend, Michael Raymen, whose boyhood trip to see the original Follies remained the highlight of his lifelong theater-going passion. There, on the dance floor of the party venue, Michael had a chance to meet Stephen Sondheim and share some private words with him, after which the gentleman and I had a brief inconsequential exchange (every word of which I can still remember) before he went off into the party. He had been simply standing there, watching the cast and crew dance, all by himself in a checked button-down and professorial trousers, holding a glass in one hand... just watching and smiling, and enjoying the show. And two strangers stopped to chat with him, one to offer compliments, the other to pass social intercourse back and forth. This man, hailed as a legend, was kind, unassuming, attentive. He was pleasant and he was present; Mr. Sondheim did not spend the moments of conversation with the strangers looking over their shoulders, he did not seek a clean exit, he did not give them the bum's rush - Mr. Sondheim remained in his lone spot on the dance floor, chatting with strangers as though they were friends until the chat was finished, polite, friendly, generous.

There is a wonderful Instagram page right now where people who have had letters from Stephen Sondheim are sharing their treasures. It is heartwarming to see his generosity so richly represented online - and anyone who writes letters, thank you notes, and cards knows the time and energy that can go into one little letter. Still, every day these days, more and more visible proof is released onto the internet, proof of Stephen Sondheim's kindness and largesse, and it's beautiful to see. That such cherished works of epistolary refinement should exist and that they should bring people joy, pride, contentment is a work of wonder.

I don't have a letter from Stephen Sondheim. I don't have a Sondheim letter because I never wrote - it's not my way. I was concerned from bothering the man and felt that anything I might say wasn't his to know, only mine to live, mine to acknowledge. It's ok. I don't need a letter from Stephen Sondheim. He gave me so much more, without really knowing it, without ever being told, and I am reminded of what he gave me, every time I see a photo I made that has a Sondheim story behind it, every time I hear a Sondheim song that has a Stephen association, every time I send a message of affection to a friend I made because of Stephen Sondheim, every time that something significant happens in life and my husband looks at me and sings, "Oh, if life were made of moments, even now and then a bad one..." I feel Stephen Sondheim in the clubs I frequent and the artists I review, I hear him on the CDs I play, and I see him in photos around my home.

Stephen Sondheim didn't inform my life: he made my life. In that life - a good life, a happy life - he will live forever.

Photos by Stephen Mosher

Photos by Stephen Mosher

Videos