Review: DAS RHEINGOLD at McCaw Hall

High Tech Meets Myth in Seattle Opera Rheingold

Opera fans in Seattle have double cause for celebration this season. For the first time since 2013, Seattle Opera is presenting Das Rheingold, the first of Wagner’s epic Ring operas, on the stage of McCaw Hall, as the initial production of its 60th anniversary season. To her credit, General Director Christina Scheppelmann deemed Wagner an important part of the festive year.

Opening night of this grand occasion delivered on its promise of excitement. With inventive high-tech staging and a number of company debuts, including distinguished singer of worldwide reputation Denyce Graves, as well as the return of such favorites as Greer Grimsley and Seattle Symphony Conductor Emeritus Ludovic Morlot, the production was a winner. The large cast was the undisputed star of the show: consistently strong and, as SO scholar in residence Dr. Naomi André has pointed out, standing out for its diversity by including many people of color.

Bass-baritone legend Greer Grimsley, the equivalent of an operatic rock star both around the world and in the city of Seattle, and synonymous with the role of Wotan, looked and sounded better than ever. With his commanding presence and vocal power, he ruled over Valhalla with an iron fist—despite the efforts of his Fricka, Melody Wilson, to take the wind out of his sails. In this all-important divine duo, Wilson stood up to Grimsley, performing with security. But for the most part Grimsley carried the show, projecting a vocal and dramatic strength that built steadily to the end.

Philip Newton

Katie Van Kooten (Freia) and Peixin Chen (Fasolt) joined Denyce Graves (Erda) in making their debuts.

Graves has had a long, illustrious career on every prominent stage on the planet, and her experience showed in her authoritative presence in this production. Her commanding performance as the prescient earth goddess made Wotan’s awed reaction all the more convincing.

Philip Newton

Van Kooten’s tones were clear and golden, appropriate for the innocent Freia. Chen made a robust impression with his giant-like presence, countering his violent brother Fafner, Kenneth Kellogg in his role debut. Both had rich, deep voices that played off each other, and both succeeded in dominating the action when onstage, especially on the neon-lit platform that grabbed attention as it moved up and down.

Philip Newton

Viktor Antipenko sounded appropriately heroic as Freia’s protective brother Froh.

Returning artists Frederick Ballentine, Michael Mayes, and Martin Bakari, gave impressive performances. Ballentine’s Loge stood out, not only for his wily characterization of Wagner’s ultimate, maddening trickster, but for his unique ability to sound like a true lyrical tenor in what is purely a character role. Mayes was an outstanding Alberich: violent, nasty, terrifying and powerful, both vocally and dramatically.

Philip Newton

Sunny Martini

Bakari made the most of the relatively small but pivotal role of Mime, cowering from his vicious brother, but adding subtle hints of his shrewd ability to fend for himself. He sang with appropriately Mime-like tones, never wavering, and piquing one’s curiosity as to his potential rendering of the character in the third Ring opera, Siegfried.

Michael Chioldi, who gave a lasting impression as Germont in the

company’s recent La Traviata, made his role debut as Donner. Chioldi made the most of the relatively small role, relishing every note and heightening the characterization, building steadily toward his moment of glory in his finale-launching thunder bolt aria, which was captivating and exquisitely done.

Sunny Martini

Sarah Larsen (Flosshilde) and Shelly Traverse (Wellgunde) in their role debuts as the first two Rhinemaidens, were joined by Jacqueline Piccolino as Woglinde. Together and separately, they sounded as lovely as three voices could be. High notes were strong and crystal clear, and harmonies resounded beautifully throughout the house. Their playfulness together in the river was hugely appealing.

Philip Newton

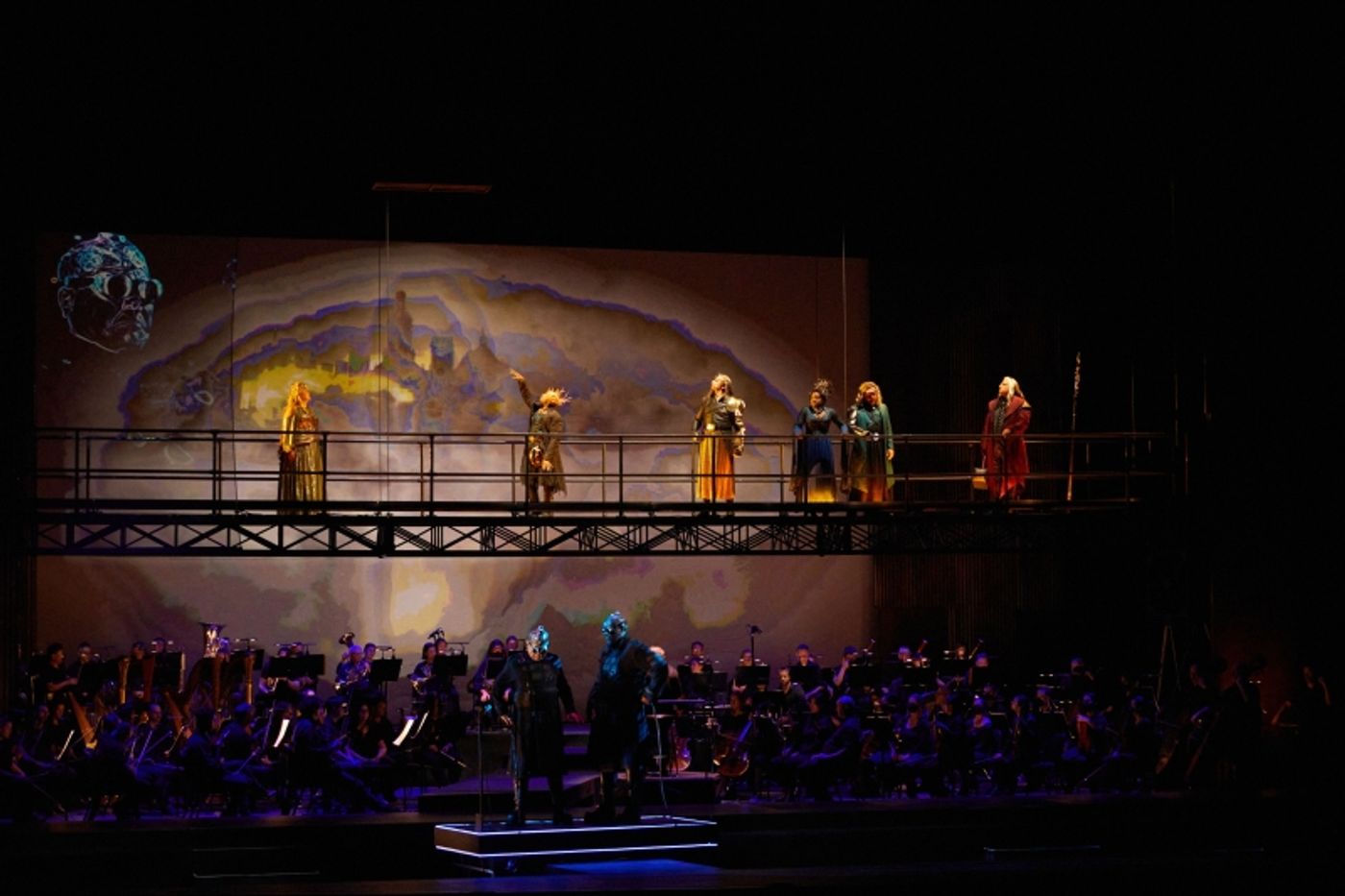

Director Brian Staufenbiel brought his 2016 Minnesota Opera production to the SO stage. Visually spectacular and undeniably thought-provoking, the staging combined the perspectives of Wagner’s ancient mythical context with a modern technological spin. Most singular was the placement of the orchestra onstage, turning the orchestra pit into an extended stage and using the pit as a split-level representation of the Rhine River and Nibelheim. The integration of the orchestra into the stage action as an active player in the drama is an interesting concept. It worked at times, and it’s always fascinating to watch the ensemble work their magic in Wagner’s ingenious score. Granted, a Wagnerian-sized orchestra will not fit into all orchestra pits. But on some level the presence of the orchestra onstage reminded one of the reasons why the composer built an opera house with a pit that was covered over so as not to distract the audience from the all-important drama unfolding onstage.

Morlot is no stranger to Wagner, having helmed the company’s 2021 outdoor non-staged Welcome Back Concert: Die Walküre. Fulfilling the demands of Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk concept, combining music with drama and integrating them as a perfect whole, is no walk in the park. Morlot managed not only to hold everything together impeccably, but he also showed an intense understanding of what the composer-conductor had in mind. As always, Morlot’s conducting was fluid, connecting phrase to phrase as if to reflect the everlasting flow of the Rhine River and the cyclical nature of the work. The orchestra responded as one instrument, organ-like in its wash of sound.

The creative team included three Seattle Opera debuts. David Murakami’s projections balanced exquisitely with Mextly Couzin’s lighting, both of which served to maximize the dramatic upheaval as it played out. Incandescent projections superimposed on the performers added to the overall impression of tech meeting traditional mythology. At times the lighting verged on brilliant, as each scene built toward the combination of light and projection in the earth tones of Erda’s spectacular entrance toward the end, which filled the entire house with eye-popping splendor. The Rainbow Bridge symbolizing the flow of the Rhine River, combined with the dazzling light that led the way to the gods’ entrance into Valhalla, made a striking last impression.

Each character looked his or her best in Mathew LeFebvre’s stunning costumes, from Wotan’s blindingly golden accoutrements to Erda’s tree branches growing from her head. The space-age headgear for the two giants, which could have seemed over the top, worked wonderfully. Even the props, from the golden helmet to the eponymous ring, stood out splendidly.

The outstanding cast and provocative production as they merged with Wagner’s indisputably monumental music and drama made this Rheingold a de rigueur happening well worth experiencing, and hopefully an entrée into subsequent Ring operas for the company.

Photo credits: Philip Newton, Sunny Martini

Reader Reviews

Videos