Interview: Steven Hao of THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN at Shakespeare BASH'd

Shakespeare BASH'd presents a rarely-performed work.

THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN is one of William Shakespeare’s lesser-known plays. Based on Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the Bard’s collaboration with John Fletcher is infrequently remembered and even more rarely performed. In it, kinsmen Palamon and Arcite, Theban knights imprisoned after a loss to Theseus’ Athenian forces, go from dear friends to deadly adversaries upon both falling in love with the same woman. Want to know what happens? Shakespeare BASH’d presents the play from January 25-February 4 at The Theatre Centre.

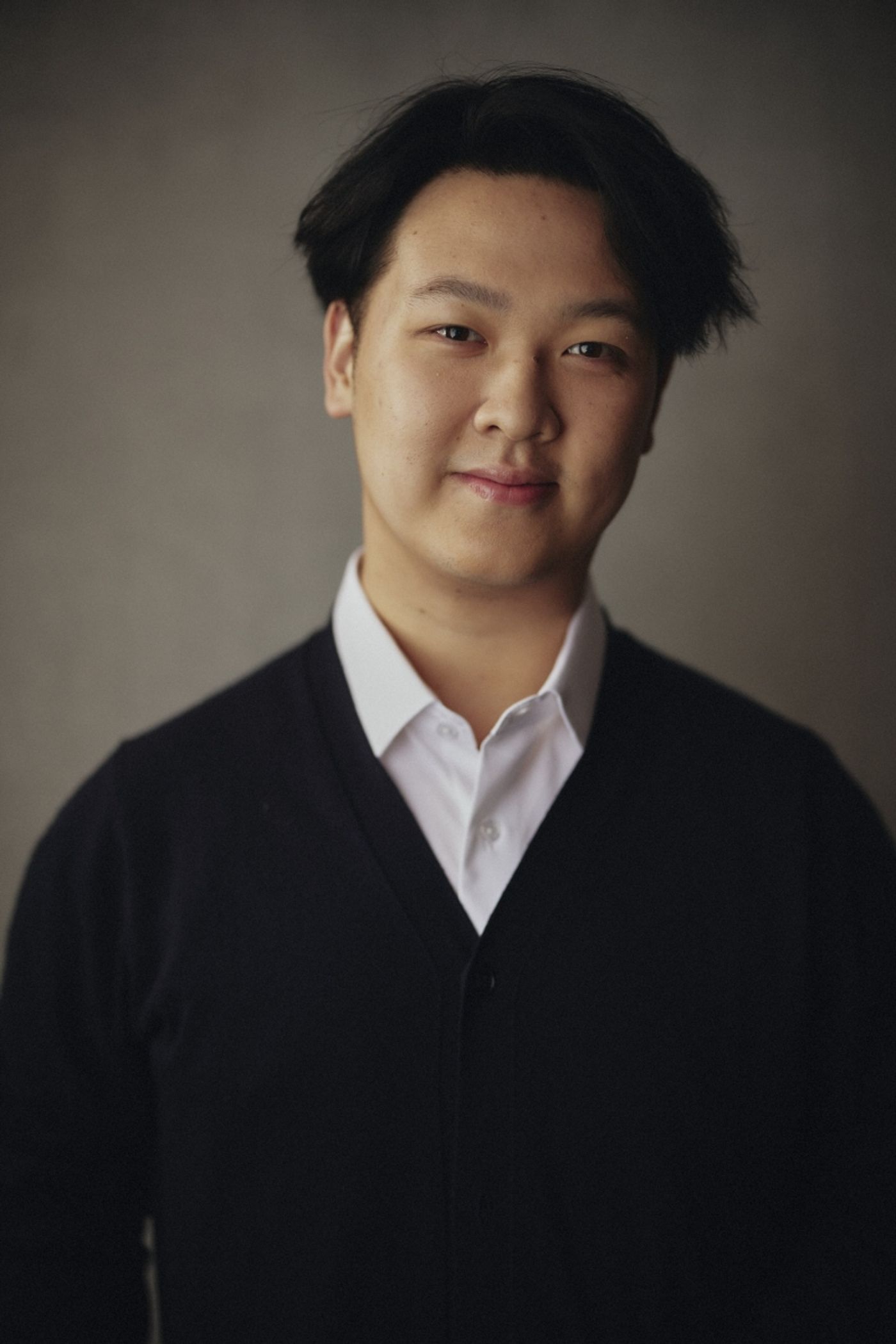

郝邦宇 Steven Hao, playing Pirithous and The Wooer in the production, spoke to BroadwayWorld about the unusual aspects of Shakespeare’s last play, why Theseus is Iron Man, and the joys of putting on one of the few works in the Shakespearean canon that's a "hidden gem" without 500 years of baggage.

BWW: What draws you to this particular play?

STEVEN: I’m a huge fan of Shakespearean work. There's so much to dig into in the stories, and there's so much to learn from in the text. When I was performing in COCKROACH [at Tarragon Theatre], this was one of the conversations that we used to have a lot as well, since the play was so “anti-Shakespeare.” But Jeff Ho, who wrote the play, is a huge fan of Shakespeare. He did a lot of his training in Shakespeare.

I think, within the world of Shakespeare, there’s just something so brilliant about it. You can subscribe to what's in the words, what’s in the story; I think, as an actor, there's just so much to learn from. Tt really helps you understand characters. Shakespearean text is so rare because the characters speak everything they're doing and thinking, all at the same time. So any chance I get to do Shakespearean texts, I'm immediately there.

Specifically about this play, I've never seen it or read it, before this production. It's such a unique hidden gem. I knew of the existence of the play, but I've never studied it or touched it. So that was at the beginning a huge draw for me, to work on a play where preconceived notions for the play almost doesn't exist. When I bring this play up to most people that I've spoken to, most people get this play confused with The Two Gentlemen of Verona, which is totally fair.

But this play is so quirky and brilliant that I think, even as a subscriber to Shakespeare's work, audiences will find themselves surprised by just how expansive a story this is. And also, it's nice to work on something where it's not purely Shakespeare, it’s his collaboration with another writer, John Fletcher, who was very popular during that time.

BWW: Would you say, then, that it’s a gift to present a Shakespearean-quality work, but also one that doesn't come with 500 years of pressure behind it?

STEVEN: Yes 100%. I think this will be a lot of people's first time seeing the play and certainly is my first time working on the play. And I don't know when I'll get to work on it again. You see plays like Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream get done a lot, and I’ll always find joy in working on those plays. But it is the rare chance that you get to tackle a play that almost didn't exist in our current realm of classical literature. I think what people will find is that there is an equal amount of merit and interesting ideas in this play to Shakespeare and Fletcher’s other works.

BWW: There’s no definitive TWO NOBLE KINSMEN film, for example.

STEVEN: Exactly. That is probably the most refreshing thing as an actor. There’s no “his Hamlet wasn't as good as like David Tennant’s Hamlet,” or “Benedict Cumberbatch’s Hamlet will always be my favourite Hamlet.” That comparison doesn't exist.

BWW: I believe that the general thought about the play is that Shakespeare was mostly responsible for the first and fifth act and Fletcher did most of the middle. Do you subscribe to that theory, and do you notice a difference between the two writers?

STEVEN: It's actually funny you asked that because our brilliant director James Wallace opened up our first week rehearsals with that information. And we acknowledge that school of thought, but it also comes with our understanding of the place and time, which is that so much of these texts are transcriptions done by the actors. Much of the actual preserved text of the writers is no longer with us. We can only assume certain things.

So I don't necessarily fully subscribe to the theory of who wrote which part, because it does seem like there's a decent amount of interspersed sections where this piece feels very Shakespearean, but this feels like a little bit more Fletcher. But what I can say is that in moments of the play where the language gets really tricky, and you fall back on iambic pentameter so you don’t get lost within what you’re saying, you find that Fletcher follows that not as much.

So suddenly you'll find yourself speaking lines where there are 11 syllables and 13 in the next and 14 the one after, and that sort of throws your mouth for a loop. I think as an actor, it's definitely easy to identify those language differences and it does feel very clear when there's a separation of Shakespearean text versus Fletcher text.

BWW: When we look at Shakespeare's text, whenever we get something like an 11 or a 12 syllable line, I know that we're always encouraged to look at those lines with intentionality, like why is there an extra beat or two. We ask, for example, is the character suddenly feeling unsure? Do you find the same thing in Fletcher's text, or does it feel like he's not as careful?

STEVEN: That rule definitely still follows. When there's not enough beats or when there's more beats, you still have to consider why that is and what information it offers. And it's not necessarily that Fletcher is more careless with it. I think it's that Fletcher's images aren't as concise as Shakespeare's. So suddenly you find these broader images are in some ways more descriptive, but also in some ways less descriptive.

Shakespeare always manages to find very concise ways to get an image across in text. With Fletcher, investigating the number of beats does more to inform how this character actually speaks. If there's already this many beats, why isn't the character speaking in prose? There's a reason why this character is still in verse. And that's been really both refreshing and challenging to work on for sure.

BWW: It’s been mentioned that there is a strong queer aspect to this play, with themes of queer love. Could you talk a little bit about that, and how that might be surprising to contemporary audiences, or maybe even a little revolutionary?

STEVEN: I think something that James always says in rehearsals and also something that I love about Shakespeare BASH’d is that we're constantly being brought back to this phrase, “don't take the text for granted.” James does such a good job of constantly reminding us of what's in the text and the assumptions that we make. What's so interesting about this play is that those lines of love between characters of the same gender are so explicit and so specific that it feels intentional, to a point that it doesn't feel like a disguise.

Shakespeare's often been theorized as having been homosexual or bisexual, you know, for all his writings about “the boy” or the quality of men. I think in terms of the queer language, this work is not new for Shakespeare, but I do think what's special about this play is that the queer love aspect of it feels much more present but simultaneously flies under the guise of honour, like in ancient Greece where sharing that respect and honour with your fellow mates is more important than anything else in the world.

But obviously in a modern context, when we look at that sort of expression of love, the queer love feels so explicit. I think what's refreshing is that, being a queer person myself, we’re portraying characters and we're bringing the contemporary audience into that world of pondering how much of this is your love for your fellow comrades as honour, and how much of this is homosexual love. That's been a really amazing discovery. and I think the audience will find themselves relating with a lot of the thematic nature in the play.

BWW: Early on in the play, Emilia says that she doesn't think she would ever love a man. Then, Arcite and Palamon, the two jailed Theban fighters, say we're not in prison as long as we’re in prison together. We have each other. It's astounding how quickly this love turns to rivalry and rage over this first glance of a woman, and there's a lot of posturing suddenly going on.

STEVEN: Totally. It’s very Shakespearean.

BWW: Speaking of contemporary audiences, how does this production deal with the role of women in the play? Shakespeare obviously wrote in and for his time, and modern audiences for the most part go along with that. But certain plays are also trickier than others to perform for a modern audience, like The Taming of the Shrew. In this show, in many ways, Emilia, Theseus’ daughter, is a prize to be won by either Arcite or Palamon. The jailer’s daughter, who doesn’t have a name in the play, is crucial. She has agency. She rescues Palamon. She sets him free, but then basically goes mad with love while he's uninterested in her. How does the production handle these roles and stories?

STEVEN: To circle back to not taking the text too much for granted, Shakespeare often wrote women not with a lot of agency. And we notice that to be true in many of the plays that he's written, where the female characters do something out of nothingness, while all the male characters have these brilliant revelations of humanity. But I think something that's smart about this play and how we are navigating the role of the women in these stories is that the characters themselves in this play, as you've pointed out, actually have a lot of agency compared with other Shakespeare works. Throughout the play we sort of see Emilia's character constantly speaking up against the patriarch of the play, who’s played by the wonderful Jeff Young, the most lovely man in the world, playing this patriarch who makes decisions for women. We see her repeatedly speak up against the patriarchy and have realizations about herself.

As a potentially queer person, early in the play, she talks about how she used to have this maid and they used to hang out, and how her love for that maid would never be replicated. What’s perhaps refreshing about this play is that we get these beautiful moments of these female characters on stage speaking to each other about womanly desires that don't necessarily exist purely within a man's world.

And there's something else that we're also doing within the jailer's daughter plotline. I mean, obviously this is the classic Shakespeare side plot where nobody has a name. It’s the jailer and jailer's daughter and I'm the wooer; my entire job is to “woo.” There is also an active investigation regarding whether she is actually mad, and what are the assumptions we can make about her being mad. Within those moments, we see the jailer’s daughter having these beautiful turns in the play of declaring her love, that for me trump those of every other character in the play. She's so honest about the way that she loves.

We're not asking the contemporary audience to forgive the play. I don't think that's our intention is ever to make sure that this play within 500 years ago is not written in a patriarchy and is not sexist. The best that we could do through a contemporary lens is to not put on those preconceived conceptions of what these characters say about each other or assume about each other.

In the textual world of this play, the wooer sees the jailer's daughter as a business transaction. His first line is, “I will estate upon your daughter as I have promised.” You know, he talks about the money aspect of this transaction of, I'm marrying your daughter because I've paid. Something that I've then made a decision on as an actor is that the rule we have to follow with that society, but it doesn't mean that there isn't room for love. Because later on the play we see these moments where she says she doesn't deserve to be loved, and I say, “that's all one; I will have you.”

There is a constant navigation and investigation for us as a company, of how to not put on a preconceived idea of what the status of these characters is immediately based on gender, but rather give these characters the agency they deserve that is present in the play, and negotiate sort of what that looks like on stage.

BWW: When I say you know she goes mad due to her love, that is an oversimplification of it because another part of it is just that she realizes, what have I done? I've set him free. What does this mean for my life, and the life of my father? So it's not just a woman going mad over love. It's a woman going mad over the choices that she's actively made and the repercussions those choices are going to have which is, you know, the best thing for any actor.

STEVEN: Right, totally.

BWW: It's interesting that you talked about your first line being about the financial transaction because that's actually kind of a callback to the opening of the play, which I thought was very interesting. “New plays and maidenheads are near akin/Much followed both for both much money giv’n/If they stand sound and well.” It's a very bold way to start a play, I think.

STEVEN: 100%. Yes. There's also a theory that the prologue and the epilogue were written after the play had run for a month or so. There’s a theory that audiences were confused by the play’s goal, so then the prologue and epilogue were added to edify and to give context. But what's true within the world of the play is that the idea of marriage back then, as much as it was about a celebration of love, was very transactional, and I think that is still very present in this play. But it's something that we're investigating. It’s not our job to judge what's there, but it is our job to take it into the contemporary context and make a sense for the story that we tell today, rather than trying to recreate or to fix.

BWW: So I know that Shakespeare BASH’d really prides itself on not necessarily a “bare-bones,” but a stripped-down, text-focused aesthetic to its shows. How do you think that that lends itself well to this production?

STEVEN: The one consistent thing that you will always get from a Shakespeare BASH’d production is that, even though you might have never read a Shakespeare play, or you might have not studied Shakespeare, or you're not an actor, when you go see your Shakespeare BASH’d show, you're still able to get what the story is. That's always been one of the strengths of this company. And for a play that's as underdone as THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN, I think that sort of attention to detail is more required than ever. If we were doing ROMEO AND JULIET, you don't necessarily need to pay that much attention to know that they both die at the end, because it's the most famous love story of all time.

But with this play, because it's so underdone and there's so few pre-existing big productions that people know of, it suddenly becomes all the more important that we really focus on what we're saying. And everything that we're saying has to have intention and meaning behind it, so that we're able to give this story to the audience. I think it’s perfect that BASH’d is doing this play because the first time I read it, I was sort of like, this is one confusing play! There's so many moving elements. But BASH’d does such a good job of translating that to just focusing on the story, so the audience will be able take away what's within the play because the story’s really clear.

BWW: When you work on Shakespeare, the actors have to know what they're talking about! Only then does it translate to the audience.

STEVEN: Totally. Totally.

BWW: Something that I think is really interesting about this play is that it takes these references to these characters that we know well from Greek myths, with characters from plays like OEDIPUS REX, ANTIGONE and PHOENICIAN WOMEN. The conflict in ANTIGONE stems from Creon refusing to give Polynices, Oedipus’ son, a religious burial after he is killed by his brother Eteocles over the rule of Thebes.

In KINSMEN, the reason why Theseus gets into this conflict with Creon which sets the events of the play in motion is that three queens come to him and say Creon has refused our husbands burial rights after conquering them in way. And to them it's not about “We want our country back,” necessarily, it's that “We want to be able to bury our husbands.” And then you get this very familiar story again with brothers—not brothers, but they're kinsmen, and just like Polynices and Eteocles, Arcite and Palamon go from being deeply devoted to each other, to fighting to the death. There are so many parallels to these well-known Greek myths.

STEVEN: The funny thing about this piece in the time that was presented is that you sort of have to take into context that people know who these characters are. The play begins with Theseus and Hippolytus having this ceremony, this wedding, and the audience of that time knows who they are. Even today, I think if you're even remotely a Shakespeare fan, you know who Theseus is, right? You'll have to fact check me, but I think Theseus is the most repeated character in all Shakespeare plays. He's everywhere. Partially because he is everywhere, you know, but partially because that character is mythical. It's kind of like today's Marvel Cinematic Universe where you go watch a movie and you're like, yes, I know who these people are.

BWW: Theseus is Iron Man.

STEVEN: Yes, Theseus is Iron Man.

BWW: And the play is also based on Chaucer.

STEVEN: Yeah, The Knight’s Tale.

BWW: Do you know how closely it's based on that original text? Or does Shakespeare extend it?

STEVEN: That's a great question, which has come up a couple of times in rehearsal. I think Shakespeare is known to take stories that already exist and adapt them right into his own versions. We see him do this in many of his history plays and also tragedies as well. And I think this play’s no different. I think there was a good degree of things borrowed from the Knight’s Tale and characters, including references within the play, and certain side characters that pop up.

BWW: Is there anything else you want audiences to know about?

STEVEN: I’m just really excited to for folks to investigate this play. I hope audiences coming in with any form of understanding of love are moved to consider what it is to have love for someone from many complex angles.

BWW: Well, I'm really looking forward to seeing it, and thank you so much for spending the time with me!

THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN runs at The Theatre Centre from January 25-February 4.

Photo of Emilio Vieira, Kate Martin and Michael Man by Kyle Purcell

Videos