Broadway By Design: WATER FOR ELEPHANTS

Water for Elephants is running on Broadway at the Imperial Theatre.

|

|

In Broadway by Design, BroadwayWorld is shining a spotlight on the stellar designs of this Broadway season, show by show. Today, we continue with the creatives from the seven-time Tony-nominated Water for Elephants- Scenic Designer Takeshi Kata, Lighting Designer Bradley King, Projection Designer David Bengali, Sound Designer Walter Trarbach, and Costume Designer David Israel Reynoso.

In Water for Elephants, after losing what matters most, a young man jumps a moving train unsure of where the road will take him and finds a new home with the remarkable crew of a traveling circus, and a life—and love—beyond his wildest dreams. Seen through the eyes of his older self, his adventure becomes a poignant reminder that if you choose the ride, life can begin again at any age.

Where did the design process begin? For costume designer David Israel Reynoso, it was with color. "I find 1920s/1930s clothes so beautiful and inspiring and wanted to find a way to bring life and color to what is so often depicted in dull sepia tones," he explained. "Yes, it is a Depression-era story full of hardship… but it felt incomplete to assume that difficult seasons in life appear only in grayscale. I thought about how in times of hardship, I find myself gravitating to glimmers of beauty as lifelines… and it made me wonder about the characters in this story: How do they find optimism despite very difficult circumstances? Where are the moments that give access to beauty… and hope… and color? And while it felt obvious that the onstage circus costumes would offer that dazzling escapism for an audience, I was equally interested in how their everyday clothes could have subtle ornamentation that provided that hope and beauty in more subtle and personal ways.

"Jess (Stone) and I started to imagine that, perhaps, a lot of the clothing that these circus performers wear would be assembled from patchwork fabric remnants and that maybe during long train rides, some would personalize their clothes with embroidery or interesting adornment and mending. Many of the details in the clothes are inspired by conversations with each of the performers. Clothes are so personal and it felt important that these details resonated with them."

"The story being a memory, sense of analogue/hands on creation of the visual storytelling, feel of dusty depression era circus, circus train, circus tent, open fields, and sky," added scenic designer Takeshi Kata.

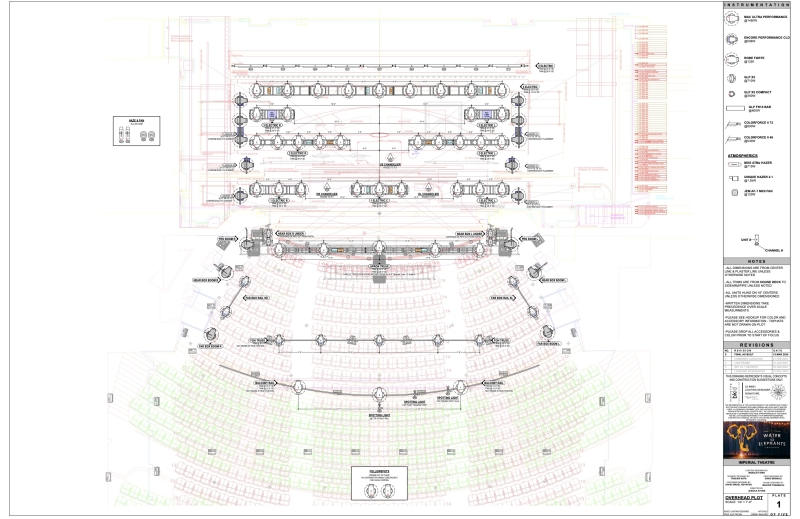

"Jessica Stone and I started meeting with Takeshi five years ago to begin discussing what kind of world we wanted to build; we landed on wanting a very 'analogue' feel to frame the depression-era circus story," said lighting designer Bradley King. "We weren't so much interested in a "black and white" or "sepia toned" world, but we did want the lighting to feel rich and motivated and incandescent - the word I kept using was "yummy." Then David Bengali (projections) brought in some incredible sky vistas by the Hudson River School painters like Bierstadt, and that grounded a lot of my color choices, especially in our sweeping outdoor scenes.

"It's a lot of meeting, looking, talking, thinking, and more thinking! I am NOT a big research person. I think it's incredibly important for set and costume and projection design, as that produces tangible content that you can look at and discuss ahead of time. But lighting is so ethereal, so interdependent on other departments, that I find you can very easily set up a director for disappointment by showing them a photograph and saying "the lighting will look like this"-- it NEVER does. Really I draw most of my ideas and inspiration from my collaborators, and most especially the music. That's the emotional core of the piece."

"In creating the projection design, I was inspired on the one hand by matte-painting skies like the ones you might see in great epic films of the 1930s and 40s, and on the other hand by paintings from artists of the Hudson River School," said projection designer David Bengali. "I worked closely with Lighting Designer Bradley King to create a sense of time, place, light, and travel for each outdoor scene. Every projection/lighting state is carefully honed to support the emotional content of the moment and to subtly reflect the internal state of the characters -- their hopes, dreams, and fears."

"The entire framing of the story as a memory play allows for great artistic license," added sound designer Walter Trarbach. "We are not tethered to history or reality, but rather connected to the emotion of memory. When this concept is expanded throughout the piece, it allows us to take inspiration from every aspect of the production. Instead of accurate animal sounds, we create soundscapes inspired by the way the puppets move around the stage. We don’t strive for “period accurate” reproduction of musical styles from the thirties, we are inspired by the orchestrations and the emotions they manifest. Every actor choice, every design idea, every line in the script or piece of movement serves as inspiration and educates us about the most effective way to present the material for the audience."

Where did the deisgn team's biggest challenges arise? King admits that the added circus elements threw him for a loop.

"I like to compare a Broadway musical to operating a giant, complex piece of machinery; there's thousands of moving parts and minor decisions that seem inconsequential can have huge repercussions downstream (changing a costume piece can affect a quick change which can affect the length of a scene transition which means automation timings have to change etc etc). But add circus elements into the mix and now you're ALSO dealing with literal dangers to life and limb. The biggest challenge for me was to really slow down. It's in my nature to get the first pass of the show finished as quickly as possible, but for the sake of the acrobats and circus performers, we really needed to move at a pace that was considered, thoughtful, and deliberate. Everything involving a circus act or trick needed to be "validated," which meant tested, viewed under the lighting conditions, adjusted, and then tried again. That's a much slower pace than many of us are used to working, but it was essential to doing it safely."

Kata had similar hiccups. "The incorporation of all the circus rigging required for the story telling. Luckily we had an amazing team of extremely smart people figuring out the logistics," he said. "Also, working out the balance of how much to remove to keep the storytelling spare, leaving space for the audience to imagine, while still keeping enough to convey and elevate each moment/feel."

"The greatest challenge for this project is the same one I find for any show for which I’m designing costumes… and that is to never get in the way of the performer or the story," said Reynoso. "And I found that to be especially true in designing the costumes for the circus acrobats. There is much to consider when someone is being flung through the air…Without question we aimed to preserve a certain aesthetic and have things be dazzling when they needed to be. But, ultimately our goal as a creative team is to tell a great story. This show very quickly bounces between time periods and also between what is behind the scenes and what is performed inside the big top for an audience. So any costume changes needed to be seamless and in support of good storytelling. And while we do have some costume “tricks” in the show, they are propelled by how best to tell this story (much in the same way choreography and acrobatics are fueled by the narrative)."

Trarbach admitted that his biggest challenges were also his greatest opportunities. "This show exists in a sound-rich environment. Between the train sounds, circus ambience, animal characters, and the extended dream sequence, there are ample opportunities for creative sound," he explained. "We were fortunate to participate in rehearsals several weeks before the cast moved into the theater. This allowed us to work with the actors and puppets to finesse the emotional and practical aspects of the sound design. The animals all have specific character arcs, and we worked to make sure we were hitting the plot points and trying to move their stories forward. We use a variety of train sounds, some comforting, others menacing and tie them to the specific emotion of each scene. By the time we get to the dream sequence at the end of act II, we have developed a palette of sound motifs from which we draw and we use sound effects as emotional short-hand to connect with the audience."

"Although the show includes a lot of video and projection, we really wanted to make it feel totally analogue, hand-made, and human. We worked hard to develop projection art techniques in combination with physical material choices that would keep the projection elements feeling painterly and luminous rather than digital," concluded Bengali "Also, throughout the show, shadows play a part in creating a world of memory, and while sometimes those shadows are cast by stage lights, at others we use projection, film, and animation to create them. Hopefully the audience can't always tell the difference!"

Water for Elephants is running on Broadway at the Imperial Theatre.

.png)

|

.png)

|

Videos