Interview: Clint Ramos Talks SLAVE PLAY's Set Design, THE ROSE TATTOO's Costume Design, Racial Equity in Theatre & More

In 2016, Ramos became the first person of color to win a Tony Award for Outstanding Costume Design of a Play for his work in Eclipsed.

In 2016 Clint Ramos became the first person of color to win a Tony Award for Outstanding Costume Design of a Play for his work in Eclipsed. Ramos' extraordinary talents as a designer have earned him two Tony nominations this season, for Best Scenic Design of a Play for Slave Play and Best Costume Design of a Play for The Rose Tattoo.

Slave Play, written by Jeremy O. Harris and directed by Robert O'Hara, follows three interracial couples in the Old South at the MacGregor Plantation. The play explores race, gender, and sexuality in 21st-century America, and Ramos' set design plays an integral part in establishing the tone of this groundbreaking show.

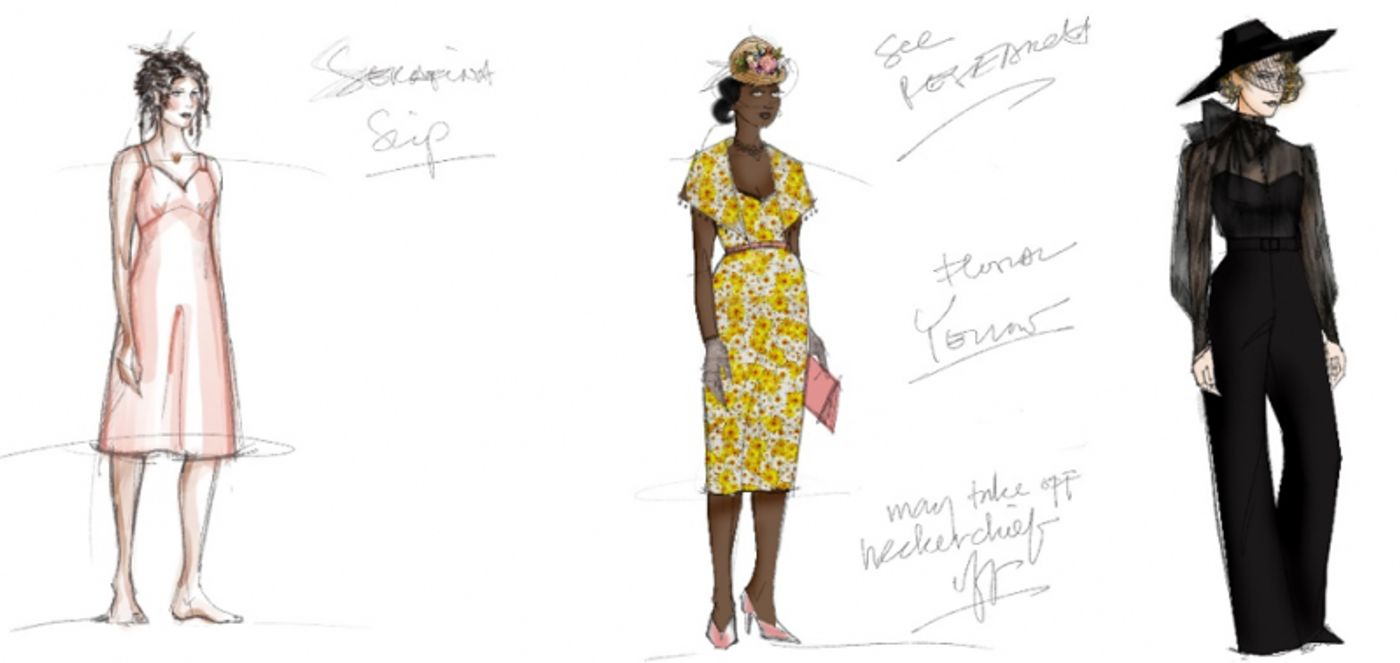

In The Rose Tattoo, a Broadway revival starring Academy Award winner Marisa Tomei, Ramos' beautiful and expressive costume design reflects the passion and personality of the play's characters, visually reflecting the elements of comedy, grief, and love.

Ramos' past Tony nominations include best costume designer for Once on this Island and Torch Song.

We spoke with Clint Ramos about his experiences working on Slave Play and The Rose Tattoo, how he is is advocating for BIPOC representation in theatre, and much more.

How does it feel to have been nominated for two Tonys this year in two separate categories?

It feels bittersweet. I'm deeply honored and deeply grateful, but it also is happening during a theatrical season that was interrupted and during a future that's unknown. More than anything, what I feel so strongly about, is we're taking the time to actually talk about the work in a very meaningful way, and it's been great listening to folks talk about the work that they've done in the past season. I'm filled with gratitude but it's bittersweet.

I want to ask you about your process working on both shows, and I'll start with Slave Play. This was a groundbreaking show, what were your thoughts after reading the play for the first time?

To be perfectly honest, I could not place my emotions after I read the play. I'm very instinctual as a designer. Robert O'Hara said, "Hey, I want you to read this script by this young playwright, he's still at Yale, and he wants you to read it." And I did, and I immediately called Robert and I said, "What did I just read?" It wasn't because I was confused or anything, I just had never encountered anything like it! I couldn't stop thinking about it after I read it. I thought, "I can't stop thinking about this play, and I can't stop thinking about how we're actually going to mount this, to make this into something that is highly theatrical." Something in me kind of broke open, and I think that's what happens, in varying degrees, to every person who's seen it, who worked on it.

How was the vision for the set design developed? Can you tell me about your conservations with Jeremy O. Harris and members of the team, and the research process for this show?

My initial conversations were purely only with Robert and Jeremy when we were ideating on the blueprint. There are a couple of things that I think were markers to how I formulated the design. The first was when I had that first conversation with Jeremy, and he basically says in the stage direction that either the plantation needs to be rendered in perfect verisimilitude, in other words, it needed to be in a plantation, or that it was as simple as a black box, nothing in between.

So, I kept that in mind, and Robert really wanted to build the play in the round. He wanted it to be intimate, he wanted the actors to be surrounded by the audience and the audience to be seeing each other. None of those options were possible, for budgetary reasons, and for Off-Broadway and on Broadway we were in proscenium theaters, so I had to think about how to satisfy the impulses that Jeremy and Robert had in those two thoughts. So, for me, I really just kept on thinking, "What is it, what is the plantation like?" and I couldn't stop thinking about how we work in a very elitist art form, and most of the people who actually go to the theatre are white. So in a way, there is something to be said about that particular kind of privilege, and all of us were doing it within this sort of white construct. In other words, we were still, quote-unquote, the marginalized.

Robert's impulse for intimacy really made me think about, "How do I do this, how do I actually put the audience on stage? How do I make them watch themselves?" I just poured into my research process. I set those two thoughts aside knowing those were the two missions. The play is about sex and desire and all of that, so one of my research rabbit holes was to look into how sex is being performed, what is this world of kink? Slave play is also a hashtag in the kink community. I looked at a lot of those windows in Amsterdam where they have all the sex workers, and it led me to this photo series of couples who like to watch themselves have sex, and in their bedrooms were a lot of mirrors.

I think that's when it dawned on me that I could do some architecture with mirrors, and I could literally get the audience onstage, get the audience to watch themselves without being physically onstage. By reflecting the audience, we made it very democratic, that the actors who were in a very vulnerable state don't feel so watched because they have the opportunity to actually watch the audience watch themselves.

And then when I was thinking about the thing that Jeremy said, like how do we place that at the plantation? I said, "If the audience is what we usually expect the audience to be on Broadway or Off Broadway, I think you will see a sea of white faces." And so, how do we place that? How do we then make them complicit? And part of it is really just making sure that the house lights never go out. The audience needs to be seen in the reflection, but also, maybe there's a way for me to actually put the plantation in the audience so it's not onstage, it comes from the reflection of the audience. So that's when that panorama of the plantation façade started. That's how I thought about that, I said, "Oh, what if the ghost of the plantation is in the audience? Just hovering in the audience."

Because whether or not in society we're black, white, anything in that spectrum, slavery is our legacy. Every single law, every single action that we have right now has, in one way or another, been informed by that policy that our nation created hundreds of years ago. And so, to me, there was something kind of like, "Oh, this makes sense to me visually, this makes sense dramaturgically, this makes sense intellectually."

Let's talk about The Rose Tattoo. Do you approach costume design differently than scenic design, or is it pretty much the same mindset? How is it different, or similar, for you?

With The Rose Tattoo, the process was not difficult for me, I loved the idea of Serafina. But, to me, I think the idea for The Rose Tattoo was, first of all, how can I relate to this? How can I make that person make sense to my own life? I feel like if I can do that, then I'm able to do that for the audience. How do I bring this woman into the 21st century? How are you going to identify with that person? To me, it really was about figuring out what that play was. To me, it was about humanity, it was about acceptance, and it was about love. And I wanted to make sure that we all understood that this immigrant woman is being othered by her community.

That for some reason, for reasons that we know, her outsider status has been punctuated. That to me was like, "Oh, yes I know this story, I'm an immigrant, I know exactly where we should go here." That's when I started digging into research like, "Okay, let me just find as many photographs of both Italian women and just immigrants, in the South," and then just poured over all of this research. And that's where I found the map for the costume design for The Rose Tattoo.

Trip [Cullman] cast it very non-traditionally. It wasn't bout race, per se, it was really about who is the outsider and who's not. And in that, it's really about who is American and who is not American. That was the difference, that to me was like, "So, Americans need to look this way, whether they're black, white, Asian, or Latinx. And the immigrants need to look this way whether or not they're black, Asian, Latinx or white." So, the differences were really about, "Who's American and who's not? Who's on the outside?" That was really the exploration for The Rose Tattoo.

In 2016, you became the first person of color to receive a Tony Award for your costume design in Eclipsed. What would you like to see more people doing to help create racial equity in the theatre industry, particularly in the behind-the-scenes positions like set design and costume design, which don't necessarily get discussed with the same frequency that on stage representation gets talked about?

That's so important to me. Part of it is exactly what you're saying, how can we find ways to talk about this? I think a lot of folks don't think about equity. Both racial equity and gender equality in the theatre, particularly offstage, because there is just no visibility. Just by the nature of what we do, and what actors do, and the performers do, there is an imbalance in visibility. Because their job is to be visible, our job is to not be. If you look at the numbers, I know Wilson Chin, the set designer, created this study with AAPAC, and for the last two years, 91% of the folks who design on Broadway were white. And that is so much worse than the actors. Their numbers are not great, but it's not as bad as the designers. We need to keep talking about it and not shy away from it.

A lot of folks are like, "These are difficult conversations to have," and I respect that sort of sentiment, but I kind of want to ask everybody, "Why is it difficult to have? Why? What makes it difficult?" These are our peers, we all talk about how we are a community and a family, and I think we have to think about it in the language of love. All of us love the theatre so much. I'm going to speak for myself. I have so much love for it, I owe a lot to the theatre . And like anything else, when you love something so hard and so much, you want it to be the best it could possibly be. And that is why, for me, that is a big thing I fight for because I know it could be better. Literally, what is preventing us from being our best self? Why can't we talk about it? Why doesn't it make sense to actually diversify Broadway? To make it more equitable.

I want to see more women stagehands. I want to see more people of color onstage and offstage. What is preventing us from doing that? What are the systems in place that are actually preserving the privilege and the status quo? As an industry, I think we need to start asking those questions. We need to start talking about it.

Can you tell me about some of what you have been doing recently to help advocate for BIPOC representation in theatre?

I've been advocating for it for years, but over the summer, a bunch of white and BIPOC designers, we started Design Action, and we are advocating for a more equitable landscape in American theatre design. We are also advocating for the inclusion of a lot of younger, and rising black, indigenous and people color designers. I am also a staunch supporter of 'We See You', I signed the document with hundreds of BIPOC theatre workers. And we can see that through that particular advocacy, that disruption, that the field is actually changing. We can see theaters that you never imagined would start talking about it make commitments towards equity and diversity and inclusion.

I think there are more groups that we want to hear from. But we see the needle moving. The field is literally saying, "We are going to be accountable, and here is what we're doing." And it's public, and people are watching it and people are saying, "Great, now you have made these commitments, now we have something to talk about." Words are important because that's what we can hold folks to.

Videos