BWW Exclusive: Jonathan Larson's College Roommate, Emmy-Winner Todd Robinson, Pens Essay About the Composer

After watching Tick...Tick... BOOM!, Robinson took pen to paper and wrote a moving essay about his friendship with Larson and Larson's impact.

Emmy Award winning screen writer and director Todd Robinson is known for his work on White Squall, Lonely Hearts, The Last Full Measure and more. But a little known fact about Robinson is that he was the college roommate and best friend of Jonathan Larson. After watching Tick...Tick... BOOM!, Robinson took pen to paper and wrote a moving essay about his friendship with Larson and Larson's impact.

Read the essay in its entirety below:

Tick, Tick, Tick... Reflections on my Friendship with Jonathan Larson

On Thursday, January 25, 1996, I was sitting in a steamy, cedar hot tub in Park City, Utah. It was the very best of times. I was there premiering my documentary tribute to film director William Wellman. I'd interviewed Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum, Sidney Poitier, and dozens of other screen legends. Robert Redford had introduced me and the film at his Sundance Film Festival, and my family was there to see it.

I had just spent the previous year at the side of film luminary and mentor Ridley Scott, traveling the world, glued to his hip as he transformed one of my early scripts, White Squall, into a big-time Hollywood movie. I was hanging out with Jeff Bridges, John Savage, and Scott Wolf, watching my dreams come true.

Surrounded by snow drifts, looking up from the frothy bath into the glowing Milky Way, I caught myself wondering if this was really happening to me, a dyslexic, bad speller from modest Philadelphia, suburbia. The only thing missing was one of Ridley's Cuban Montecristos and a chilled glass of 18-year-old Macallan's.

Holding the hand of our four-year-old Tyler, my wife Elizabeth crunched through the snow, interrupting my private reverie. With four words forever burned into my mind, it all came crashing down as she said...

"Jonathan Larson is dead."

* * *

My first impression of Jon was memorable, as was the last. To be accurate, I actually heard him before I saw him.

I had transferred to the Theatre Conservatory at Adelphi University from a small college in upstate Pennsylvania with my girlfriend, Francine Bianco-Tax, to study acting with Jacques Burdick, Nicholas Petron, and others. They had matriculated from the Yale Drama School to start an undergraduate repertory theatre program and we wanted to be part of it.

All incoming thespians were required to spend a rigorous first semester in what was, and still is, called "Freshman Workshop", a theatre-geek version of Marine bootcamp.

We were forced to wear black leotards and a wraparound floor-length tunic, described as an Old Vic skirt. To this day, I'm not sure of the purpose of these togs, except to create sameness and remove any sense of significance left over from our lingering glory as the stars of our high school musicals. I suppose it was our faculty's version of buzz-cutting the plebes.

As I climbed the stairwell inside Post Hall, passing normally dressed students in my embarrassing, unexplainable regalia, I heard the machine-gun staccato notes of a piano ricocheting into the hallway from our rehearsal studio.

Inside, forty-some clones of myself sat on the floor, stretching, whispering, uncertain, bracing for what was to come.

Sitting confidently behind a baby grand piano was a lanky dude with exaggerated features and a 1970s white-man-curly fro, attacking the keys with the grace of a jackhammer, bashing out the rousing intro to Billy Joel's "Angry Young Man."

Meet Barnes Scholarship recipient Jonathan Larson. I'd been in his presence less than thirty seconds and I already didn't like him. After he finished, he stared with satisfaction at the keys as if he'd just summited Everest without needing oxygen. I wandered over to introduce myself to this cat. I had to see if he was for real.

I nodded as if his playing was only adequate. (It was way better than that, even if it lacked dynamics.) He was tall, I'm not. Another reason for skepticism. He jutted out his chin and looked sleepily back at me, as if I was a troglodyte-groundling who had paid for the privilege of witnessing his beneficence. I was an athlete turned dancer. I was in shape. He wasn't, and noticed. He didn't approve of me either.

I offered that he must be a fan of Barry Manilow, the piano-playing, pop singing star of the age, who fused show-tune storytelling with a keyboard-centric, singer-songwriter style. It seemed logical. A harmless, awkward icebreaker.

He looked at me for a moment, probing for sincerity. Seeing that I was, he twisted his face, stood, taking full advantage of his height, and simply said - "Are you insane!?"

Thank God I hadn't asked him a leading question like "Who are you? What do you do?", as my best pal Eddie Rosenstein would do a decade later. Because if he had answered me the way he'd answered Eddie with "I'm the future of The American Musical Theatre", my pugnacious nature would have required me to punch up and drop him.

Fortunately, we didn't come to blows. This was the theatre. A civilized world of nerdish misfits and reprobates. And we were, after all, wearing dresses. Dr. Burdick entered the room and both our education and scrappy, competitive, deeply loyal, blood-brotherhood began.

After circling each other like rutting elks on some frozen theatrical tundra, Jonathan and I figured each other out and separately, simultaneously, came to the mutual conclusion we weren't adversaries at all. On the contrary, we were simply brothers of other mothers, spun of the same threads of curiosity, creativity, commitment, drive, ambition, and a deep need to be heard. By the end of the semester, we had already cast out our assigned dorm-mates and plotted to begin our own tribe.

Membership required true-believer-ship in the messaging of department chair Jacques Burdick and his disciples, along with guts enough to call bullshit whenever one witnessed anything inauthentic, which was encouraged by Burdick himself. It was fair game to stand up and declare "Stop this shit!" in any performance that revealed pretension or laziness.

We also shared an addiction to music in the days when listening also required pouring over liner notes, pulling apart voicings, progressions, mixes, and arrangements to deconstruct the process of making art. We did the same with the written word of the great plays, books, choreography, and even editorials and reviews in the New York Times - not to mention the curriculum we were studying. We wanted to consume, understand, and master all of it. We wanted a life in the theatre.

In short, we were splitting the creative atom in all of its forms. While Jon and I squabbled from time to time, we were equally committed to an art form where we wanted to leave tracks. We began shaping each other with a creative conversation that would last almost eighteen years, unknowingly preparing each other for lives and careers we couldn't possibly imagine were coming - his as composer, mine as filmmaker.

* * *

For the legions of Jonathan Larson fans, colleagues, promotors, and all who came after, Jon's story begins on the same day that, for those of us who deeply knew and loved him, it ended.

January 25, 1996.

A recent New York Times article reflected on the work of social scientist Pauline Boss and her concept of "ambiguous loss", an abstract that instantly resonated with me. In brief, she posits that closure over grievous loss might be neither achievable nor even desirable. Rather, she offers, loss is something to be acknowledged, managed, and lived with and that "simultaneous absence and presence" is part of a natural state of having a human experience. This couldn't be truer for me than with Jonathan, the ultimate proof of concept.

Jonathan has been gone just over twenty-six years as of this writing, and yet he remains everywhere.

As we were trying to grieve our friend in 1995, another story was being written. It was the story of Jimi and Janis, Norma Jean, and certainly Martin, Malcolm, and the brothers Kennedy. As one of Jon's rock heroes, Billy Joel, would state musically, "only the good die young". As I longed for relief from my sadness, a massive, global transmutation was afoot. In death, Jonathan Larson was becoming an unimaginable superstar.

There would be the Broadway rendition of Rent, a show that ran for more than a decade, garnering four Tonys and a Pulitzer, and more, countless road tours, and international productions in dozens of languages. There was a movie, a live TV version, and record albums. Stars would record "Seasons of Love", now a standard, many times over. tick, tick... BOOM!, Jon's rock monologue about turning thirty while examining purpose and meaning, was remounted off-Broadway and has recently become Lin-Manuel Miranda's opus freshman directing project.

At the recent premiere of the film, someone deep within the Larson business camp whispered to me there was even more to come. I swallowed hard.

On the one hand, creating the permanent legacy for Jonathan was something I wanted most, and it had happened. He will never be forgotten and all the music no one ever heard in his lifetime (except his friends) has been claimed by the ages.

On the other hand, it has simultaneously, unexpectedly been an emotional scab that has been torn open again and again by fans, strangers, interlopers, and yes, the occasional profiteer.

I have heard Jonathan's music in a restaurant in Santa Fe (guess which one), a beer garden in Munich, a grand hotel in Bangkok, Harrods in London, and many places in between. It's inescapable, inspiring me, yet fueling my sadness and longing for my friend. "Simultaneous absence and presence." No shit.

An untimely death drove Jonathan's stock way up. It's impossible to separate the bitter, delicious irony of his passing (during the peak of the AIDS scourge that took so many of the brightest and most talented of our generation) from the thoughtful, poetic elegance of his glorious anthem "Seasons...".

It is an amazing, convenient, highly exploitable set of sad coincidences. With the slightest salting of dramaturgy and the tiniest bit of contextual manipulation, you have, embedded within the tragedy of Puccini's Bohemia, a highly marketable story regardless of Jonathan's actual message. As the mythology grew, I was reminded of a line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, "When the legend gets bigger than the man, you print the legend."

A friend who makes his points with deeply Socratic, rhetorical questioning often asks, "Are you who you say you are, and does it matter to you?" Jonathan was human as they come but entirely authentic. He was writing about what he knew and was experiencing day in and day out. AIDS in the '80s was nearly entirely fatal and a horrible death. He was celebrating our people as they were being lost week after week, for years. Jon didn't write Rent because he wanted a gigantic hit, though he would have benefited from and enjoyed the validation. He wrote it because it was the only thing he knew to do to process his own frustration, outrage, and grief. Ironically, it became his epitaph.

For Jon's friends and family, the global success of Rent is an ongoing if somewhat hollow memorial because the metrics of its success don't accurately reflect the person who inspired, infuriated, and challenged us to never ever settle for anything less than the truth. I'd like to think we did the same for him. In any case, our pride in Jonathan's legacy walks hand in hand with a low-grade heartache that rises like Vesuvius when his victories swell.

* * *

As a transfer student at Adelphi University, I was required to make up classes over the winter break known as "intersession". It was six weeks of Long Island's gloomiest weather and campus was empty. I was lonely and Jonathan decided to drive out from White Plains so we could settle our room and he could keep me company for New Year's. Adopting orphans was something Jon would become well known for, hosting his famous "Peasant Feasts", ensuring nobody he knew ever spent a holiday meal alone.

There were several things you knew about Jon pretty quickly. He was extremely confident. He was a devotee of Billy Joel, Elton John, The Who, and oh, Stephen Sondheim was God. That was not up for debate. If you didn't agree with him on that point, fuhgeddaboudit.

Jon was already sitting on his bed when I came in from class. He made me put everything down and sit symmetrically across from him. He was way feng shui before it was cool to be so. Once I was seated, with the door closed and locked, he withdrew an envelope with great fanfare. From within, he withdrew a letter.

It seems he had had the audaciousness to write a fan letter to the mysterious and powerful Sondheim, and he now held between his fingers a handwritten response from the man himself. He made me sit silently, motionless, as he read the words of the master aloud, twice. I have no memory of what it said, but I do remember that he would neither let me hold the letter with my unwashed, unworthy hands nor let me see the envelope because it contained the great one's return address. It felt like we possessed the Dead Sea Scrolls and he swore me to secrecy. I half expected him to prick my finger and place the burning picture of a saint in my hand.

Either way, we became the brothers neither of us had growing up and we formed our own little street gang right there. Membership required preapproval. I was content to coattail on his confidence, even though it nearly got me kicked out of the program. One might sum it up as overconfidence and cult-like commitment to Jacques Burdick and breaking down his cipher-logic style of teaching. Except the faculty missed the point.

This would rear its head during a faculty jury we were all required to go through twice a semester. I had pretty much prepared myself for the Presidential Medal of Freedom for my potential alone. As a transfer student, I was a year older than my classmates and certainly had some entitlement issues. In short, I guess I thought I was special.

Instead of being praised, I was shredded for what felt like everything, including being born. I was put on probation and told I might be asked to leave the program. What?!!

I left the jury in shock, a cloak of shame draped over me like a wet blanket. I went back to our room and wept. I was devastated. Jonathan was there for me. We talked it through and he helped me quietly come up with a plan to turn it around, and I did. He helped me interpret the real message. Assimilate.

On his advice, I kept my head down and my mouth shut. I looked around at my talented classmates and tried to learn from them. I endeavored to become what the Navy SEALs call "a gray man", somebody who does the work but remains invisible to the instructors who have the power to torment you. At my second evaluation, the faculty puzzled over their notes and shrugged. They couldn't remember why they had been so critical and admitted they must have just gotten me wrong. The fact was, they got me right and I had received the memo loud and clear.

In large measure, I have Jonathan to thank for that because he never stopped believing in me until the day he died. He was waiting in the hallway when I came out of my second jury and simply said, "Well?" When I told him, he shrugged and chortled, "See?! Let's get lunch." And that was the end of it.

I excelled from that point on and even left drama school a semester early to begin working as a professional actor at the Denver Center Theatre Company where I received my Equity card. I owe much of that initial success to Jonathan. He was a true friend in the trenches. You don't forget that.

Our dorm room in Garden City, Long Island was the birthplace of an ongoing conversation that would carry us through to the end of his life, which as everyone knows came far too soon - a life snatched away by a sloppy diagnosis of an undiagnosed genetic condition called Marfan Syndrome.

* * *

I have so many memories of our college productions and the dozens of classes and stages we shared. One curious thing: Adelphi didn't do musicals. Not only was this odd for me, an actor/dancer, but for Jon too, who was an actor/musician. The closest thing to musical theatre was what we called Cabaret Theatre, a student-written form that blended song and dance with sketch comedy and satire, loosely held together with some topical theme. It was heavily influenced by SNL, which was in its golden age.

If we weren't cast in these productions, we were often recruited to play in the band - Jonathan for his keyboard skills and mine for guitar. It was there that an awakening began to happen for Jonathan. He started supporting theatrical ideas with music. Plots and storylines could only become complete through song and movement. The light bulb was going off for him. There was something bigger out there than just acting.

It came together when Dr. Burdick asked Jonathan to work jointly on the 1980 Freshman Workshop called "El Libro de Buen Amor". He may not have realized it at the time, but Jonathan was about to write his first musical. A Quixote-esque epic about finding true love, in what became grand in emotional scope because of Jon's natural ability to create emotional subtext with music. From that moment, I think he knew he had found his way forward. The experience was transformative.

* * *

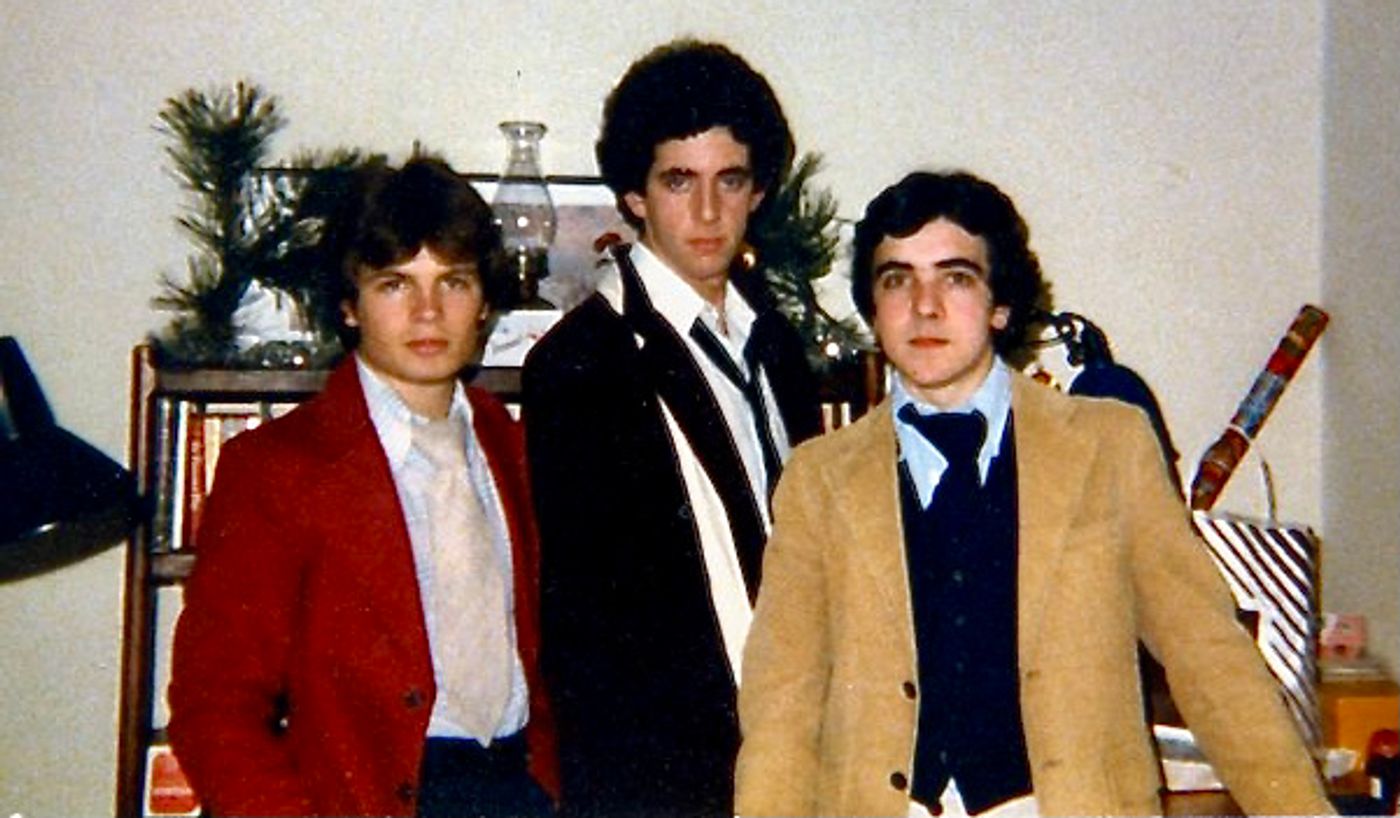

After two years as dorm-mates, we outgrew the restrictions of our penitentiary-sized room. In our junior year, we added Tom Buderwitz to our creative cloister and took over an apartment in Hempstead. (Tom is a prolific Los Angeles set designer and I'm proud to be godfather to his kids.) It was a one bedroom in which Jon and Tom erected a middle wall while I turned the breakfast nook into my domicile.

Roomies Todd Robinson, Jonathan Larson

and Tom Buderwitz.

Bad ties and hair, one and all

The elevator never seemed to work and I became acquainted for the first time with cockroaches. The place was littered with Roach Motels, a disgusting remedy in urban living. They liked to eat the grease off the stove. Jon took great pleasure in sneaking in, in the dark, humming "Say Goodbye to Hollywood" while snapping on the burners like land mines, happily exterminating the scourge.

Each of us bought bicycles for transport to school and fixed the place in hipster-nihilist style, the crown jewel being our gigantic Frankenstein'd Techniques stereo. To us, it was more precious than a car.

We had a great time in that apartment, ironically like Jonathan's final address, on a street called Greenwich. It was our first real experience of independence, dividing responsibilities and being responsible for bills. We had epic parties there, experimented with illicit substances, and even experienced a taste of domestic life with regular Sunday brunches for invited guests. Jon liked to cook and I especially remember his rather extravagant French toast recipe: sourdough heavily soaked in eggs, milk, and cinnamon, piled high with fruit, drowned in syrup, with a dollop from a Reddi-wip can that we alternately took turns sucking the nitrous out of. Ah, youth.

At this time, Jonathan and I formed a musical trio - Jon on keys, me on guitar, and fellow theatre major and alto Perry Chuto fronting the band as vocalist. We could have used a bass player but couldn't find one. We played beach dives across Long Island and in the city, doing a hybrid list of pop songs and show tunes. Often, we'd play comedy clubs during intermissions between comedians. It was in those places we learned just how cruel audiences could be. They were usually fine with us, but for a poor comedian who was bombing, it could get tragically ugly!

Another crazy thing about the apartment was it overlooked a funeral home. We routinely watched the employees flip a Frisbee below or play stickball in the alley, then moments later stand solemnly as the bereaved arrived.

Once, we even had a customer for them in the building. A man had died on the first floor. Nobody seemed to notice or care until weeks of mail piled up. The Super didn't bother to check on him until the rent was overdue. They evacuated half the building after they opened the door. It was the only time we were grateful to be on the top floor of a four-story walk-up. When our neighbors from the funeral home retrieved the body, they seemed unaffected by the rancid smell of rotting death. Soon they were back in the alley playing disc football.

We would never view death the same way. Life goes on and we were content to be witnesses to the circus of the seasons going 'round. We thought the cynicism with which professionals in death approached the world was kind of funny.

But nearly two decades later, when Jonathan died on his kitchen floor, in another apartment on a street also called Greenwich, I thought of the strangers who would come to pick him up. I knew from personal experience those Frisbee flippers wouldn't give a shit about my friend. It haunted me for a long time and I felt ashamed I had been so cavalier about something so intensely personal and agonizing for those left to grieve.

Jonathan and I would share other apartments, which would all look similar. Our junk would follow us - beanbag furniture, butterfly chairs, stackable fruit boxes full of record albums, creaky bookshelves, and third-hand kitchen utensils. And books. Lots of books. If you look at the apartment set in Lin-Manuel Miranda's tick, tick... BOOM!, you will see an historically factual recreation of our living conditions. Many of those materials spent time at our upper West Side address yet to come.

* * *

After leaving college for the Denver Center Theatre Company, I gypsied my way around the country in various shows for a year. When I returned to NYC, I settled into a ground-floor apartment at 782 West End Avenue. This was a tiny studio. I'd graduated a year before Jonathan, but once he was out of Adelphi he moved in.

This place had a spectacular view (not) through fire gates into the alley with garbage dumpsters below. But hey, we'd made it to Manhattan!

We built a loft from reclaimed wood from the movie set Tootsie. (Years later, I worked for the film's director Sydney Pollack and thanked him for my bed.) I slept on top and Jon below me on the pull-out couch. It was mostly tolerable because my girlfriend lived upstairs in a grown-up apartment, and I spent a lot of time there.

At one point, Jonathan found a derelict spinet piano rotting in somebody's garbage pile a few blocks away. We hustled down and rolled it up Broadway. Somehow we got it up the steps, past the building Super, and jammed it into the corner of the main room which was about eight feet wide and twenty-five feet long. Weird. The piano was absent its top, missing ivory on some keys, and woefully out of tune.

What is it they say about "one man's trash is another man's treasure"? The universe knew Jon needed a piano and provided one. Jonathan wrote songs on that old jalopy that today reside in the Library of Congress. For all I know, that piano is still in that apartment because I left it there when I moved to Los Angeles.

* * *

During the summers, Jonathan went to his happy place, Nantucket Island, where for two summers he shared a house with my sister Traci, a singer, actress, and classmate in her own right. It was a creative retreat for him where he could see an ocean for inspiration rather than the charcoaled walls outside our caged city windows.

Jon and Traci quickly formed a duo and played standards in a restaurant/bar called The Club Car, which is still there. I visited Jon and Traci. It seemed they, along with the other young islanders, were having a crazy good time. Singing by night, writing music and soaking in the salt air by day. Looking back, I'm pretty sure our 20s were far better than we thought at the time. Wistful freedom from responsibility, interfered with only by ambition.

* * *

My film White Squall opened the week of Jonathan's passing. I managed to make the Hollywood premiere and was soon on a plane to New York for Jonathan's memorial. The weather was awful all across the country, coating everywhere east of the Mississippi with ice.

As I flew across the heartland, I scratched out the eulogy I would present the next day to mostly strangers. The service would take place in a theatre in Greenwich Village, and along with my sister and other family and friends, I would try and push through my shock to somehow make meaning of this unthinkable, unexplainable loss.

I don't remember much of what I said, though Jon's sister Julie has a tape of it somewhere. There were only two things I knew I wanted to accomplish in those mad moments of grief, the first of which was to help create a foundation in Jonathan's name so he would have a legacy.

Within the year, along with Julie, her folks, and others, we had created The Jonathan Larson Performing Arts Foundation, of which I had the honor of being an original Board Member. It would benefit struggling musical composers so they might know the name of a benefactor and kindred spirit and understand there was an "angel" somewhere watching over them, whispering comforts while they struggled to develop. Today, the Foundation is in the hands of The American Theatre Wing and continues in perpetuity.

The second promise I made was more personal, and harder in a way, because it would require my being vulnerable. I committed to try and fill part of the hole Jon had left for his family. This would require both my time and pressing into the uncomfortable grief of loving parents and a sister.

I engaged with the family and created a deeper connection, especially with Al, Jonathan's dad. We teamed with the Foundation project and grew close, speaking openly about our shared loss, and over time I felt as if I was bringing some relief into Al's life, if only in moments of distraction.

There was more in this for me than I possibly could have known. For one thing, I came to understand where Jon had gotten his worldview. Al and I picked up the same conversation Jonathan and I had been having for years and which Al had been having with his son for a lifetime.

Al was a WWII Navy veteran who had fought bravely in the Pacific Theatre. In fact, his ship had been nearly taken out in a kamikaze attack. Al had lost friends in the war and seen the worst humanity had to offer. It was an honor to hear his stories.

My dad was a Naval veteran of the Korean War, ripped away from his young wife through the draft, giving two years of his life on behalf of his country. These men gave so much more than my post-Vietnam-era generation would ever be asked to give.

My dad was my best friend. He was wise counsel and, along with my mom, my greatest fan and supporter - as Al had been Jon's. Now here I was, trying to fill that hole for Al, as if I was even worthy of the task.

Then something shocking happened. In January of 2006, at 76 years of age, my dad died suddenly of a brain aneurysm. Ten years later, practically to the day Jonathan had passed and basically from the same malady. A burst blood vessel.

For me, the loss was immediate and devastating. And who was there to pick me up, to support me? Jonathan's father Al. The man whose heart-hole I'd promised to help heal. Never had it occurred to me it would be him who would help fill the hole left by the most important man I would ever know.

I deeply appreciated that at eighty years old he made the drive from New York to Philadelphia for my dad's memorial service. He didn't know my parents, but he'd made the journey to support me, my sister, and my mom, and we were so deeply grateful.

They say a boy isn't a real man until he loses his father. Apparently, I will learn this lesson twice. Al crossed over the rainbow bridge Thursday, December 23, 2021. I appreciate and love Al every day for being there for me. It was a tiny but powerful miracle. The angels matching a father who'd lost a son with a son who'd lost a father. We had become mutual heart-hole fillers.

* * *

Ten years earlier, as I completed my remarks before those gathered at Jonathan's memorial in lower Manhattan, I passed the next speaker, Eddie Rosenstein. When I moved from New York to Los Angeles, it had left creative and friendship vacuums in Jonathan's life as it had mine.

I had never met Eddie, though I had spoken to him and Jonathan on the phone together a few times. They'd asked for notes on a screenplay they'd written. As I recall, that hadn't gone entirely without controversy. What could I say, it was a period piece about a shipwreck - with subtitles. Not an easy thing to get past the executives at the studios back then.

What would later rub salt into a wound of frustration was that my own period, seafaring, shipwreck story was about to roll into movie theaters across the globe. When the two learned of my selling that project a year earlier, there was some half-hearted grumbling, though the stories were in no way related.

Jonathan couldn't understand how the bad speller was making a living in the screen trade while he served greasy lunches and brunches to the ferocious hungry hordes, especially on SUNDAYS!, God's day of rest for composers. Eddie was Jonathan's greatest defender, so he dismissed me on principle. Lottery winners... meh!!!

Regardless, here was my accuser, my replacer, Eddie Rosenstein, hugging it out with me on a stage in front of hundreds of bereaved.

Eddie had met Jonathan at a party years before and had become transfixed, appalled, and befuddled by Jonathan in the same way I had at my first encounter. It was Eddie who confronted him with the deeply complex and probing question "What do you do?" If I were to recreate the moment in a screenplay in order to get Eddie's correct intent and inflection, it would read something more like "Hey, schmuck, who the hell do you think you are?" Which would have been blunted matter-of-factly with Jon's actual, now-infamous "I'm-the-future-of-the-American-Musical-Theatre" retort.

With that, Eddie slid effortlessly into the vacancy my leaving had created. Like Jonathan and me, they rumbled like battle-bots and in the process became the closest of friends. Eddie was a struggling documentary filmmaker who has gone on to make many important, award-winning films. I was also making docs. (Read into that what you will, Rent-heads.)

Eddie was the person who, in Jonathan's final days, was his closest companion. He took him to the hospital when he complained of chest pain and found Jonathan's body on his kitchen floor, in the darkness of night, a boiled-out teapot glowing red on the stove. Eddie was traumatized by this event and carries guilt that he hadn't done enough. Of course, he had no idea what was really happening. Not even the doctors at multiple hospitals had caught Jonathan's killer malady.

So Jonathan complained to Eddie about me and to me about Eddie. Typical triangular venting that only happens within the circle of trust. As a result, Eddie and I developed an uninformed, squishy mutual antipathy for each other without ever actually meeting until that moment on that downtown stage.

We were each startled to realize who the other was. But Eddie had heard my grief and I his a moment later. We instantly understood that we both knew Jonathan deeply, authentically. We were bonded instantly in our mutual love for the same friend who we now had to carry on without.

Where one window closes another opens.

What I didn't know then, what I couldn't have known, was that Eddie would truly become one of the most important men in my life, one of my very, very best friends, and we've managed to do that living on separate coasts. I have known Eddie for twenty-six years now, nine years longer than I knew Jonathan. We watched our kids grow up, go through college, and now mine are both getting married. I even gave his son August his first small role in a movie. He and his family will join us for our children's weddings, like so many other things... like the day I buried my dad, Eddie was there too.

You see, this was Jonathan's parting gift. He gave us a friendship that might, but for his own passing, never have happened. I can speak for both of us when I say we are eternally grateful.

I don't remember much about Jonathan's memorial. I know friends gathered after but not much more. It wasn't a celebration of life, that would come awkwardly later, narrated by others. It was more of a piercing of the shock bubble.

I do remember it was bitter cold and Black Ice coated the streets and sidewalks, making movement treacherous. The steely gray skies of Manhattan seemed to wash away the lights of Broadway, as if draining the joy of Kodachrome of the '90s back to the monochromatic glass-plate photographs of a century before. It was as if a blanket of icy sadness enveloped me, freezing my emotions.

For people like me, opening movies that weekend was a force majeure of punishing proportion. There was no streaming to pick up the slack. Everybody stayed home. JFK shuttered its runways and I was trapped with my thoughts in a city that felt more like a crypt than a place I often longed for. I just wanted to go home.

* * *

Nearly a year before to the day, I was packing off to location in the British Virgin Islands to begin shooting White Squall. It was an adventure I will never forget. Jonathan had closely followed the development of the film. After all, if not for him, the movie would never have been made.

If not for his love of Cape Cod and Nantucket, my sister Traci would never have gone there to live with him. She would never have met Chuck Gieg, the central character in White Squall, and never would have introduced me to him and, well, no movie.

* * *

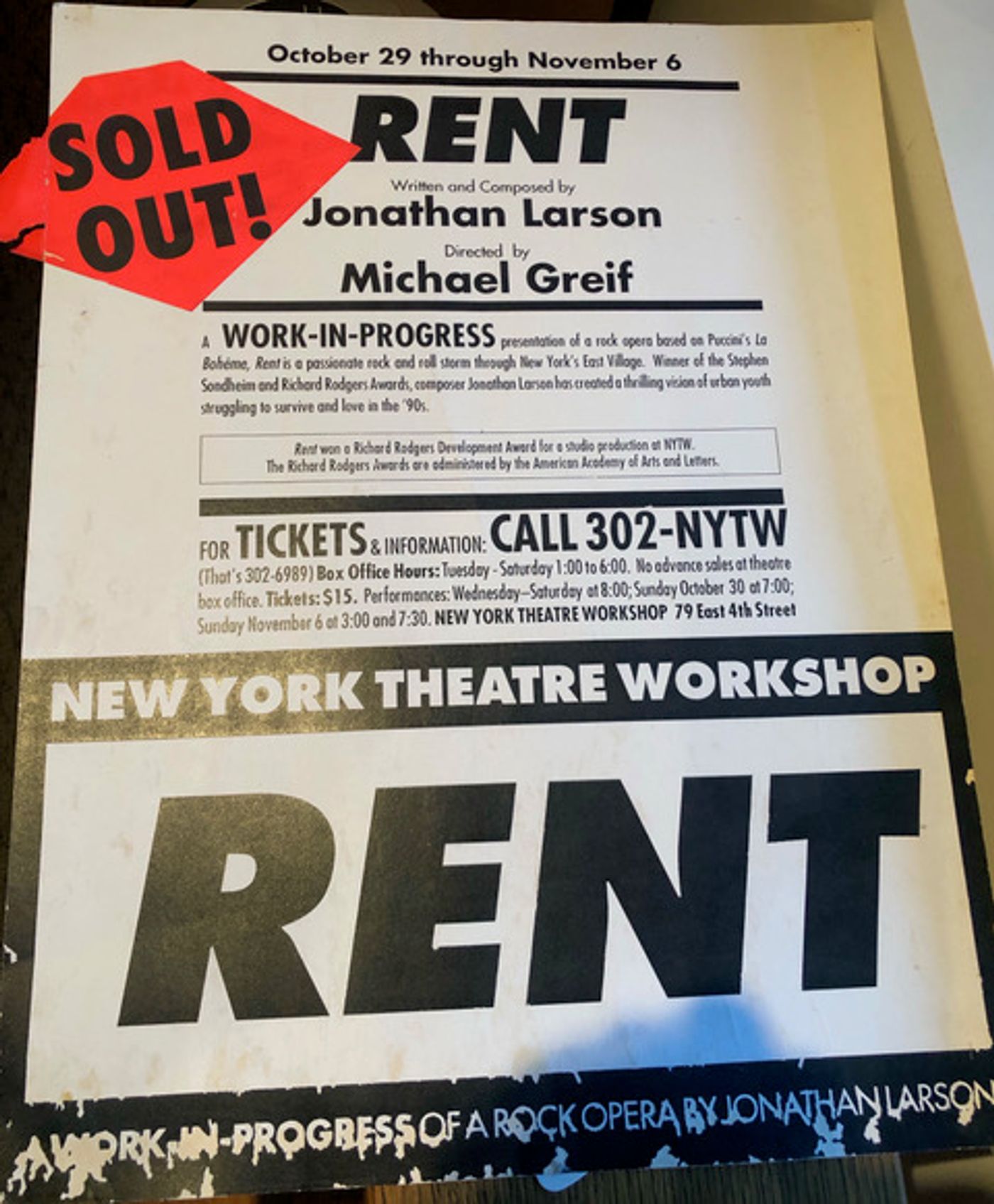

At this point, I had already seen a staged production of Rent at New York Theatre Workshop in the autumn of 1994. That earliest public performance concluded with an endless, rousing standing ovation. I've probably watched the show fifty times since then and I've never seen a single performance, in any country or language, that didn't end the same way.

When Jonathan called and asked if I would come and see that initial workshop, I got on a plane. I wanted to be there for him. I wanted him to know that what he was doing was worth me flying across the country. Not because of what it was, but because we were still a tribe. Womb to tomb.

I'll never forget running cross-town, desperately delayed by a derailed subway car, and racing into the theatre in a flop sweat just as the lights were going down.

Now, I had been reading and listening to various iterations of Rent literally for years - Xeroxes of handwritten versions of the libretti, faxes of lyrics, and endless cassettes of Casio versions of songs you almost couldn't recognize now.

I knew it was good and Jon was doing what he said he was going to do - blending popular musical idioms within the structural format of musical theatre. But I had no idea what he had actually done until I was within the glow of a theatre where, for the first time, he had the control and attention of a real audience.

We've obviously made LGBTQ progress since then. But when the character of "Angel", a man, came out in drag in that gender-bending Santa costume and ripped into "Today 4 U", it was a little shocking, even by East Village standards. It wasn't a subject you waved under the noses of "The Ladies Who Lunch", let alone matinee audiences from Long Island and New Jersey. It was bold, risky, and dangerous in its time.

I was in the back row, peering through a sea of conservative blue hair, and I remember wondering if these people were going to get up and leave. They were noticeably uneasy. But (spoiler alert) by the time Angel died in the second act, you could hear people audibly stifling sobs... myself among them. It was so moving. So powerful. That was the moment I really saw Jonathan's guts and genius.

You see, with Angel, he puts something in front of you and forces you to feel uncomfortable, to privately lean into your bias, your fear, and form an uninformed judgment. Then he forces you to see all of that through a prism of love. My response was not simply reactive. It was deeply personal as I found myself in an uneasy conversation with myself about such bias and how we revert to fear as a default setting when we're unfamiliar with something or someone that might seem different.

"Make the unfamiliar, familiar. Make the familiar, unfamiliar." Jacques Burdick.

Jonathan didn't just ask that dramatic question, he confronted the audience with it, pushed fear buttons, dismissal buttons, because he was pissed and hurt. What happens when an unspeakable, unexplainable, existential scourge wipes out a generation of your heroes, mentors, and co-creatives?

When his best childhood friend Matt O'Grady was diagnosed with the death sentence of HIV, that was it. Jonathan was coming for us. He double-dog dares you and then inside of three hours heals you with empathy, love, forgiveness, gratitude. He understood these things, especially fear and love, could not coexist in the same space in time. Those are the conditions he created in Rent. He sets you up and then asks, "Who are you? It's one or the other. Choose." That is the undeniable power of his dramaturgy.

Even then, I had no real understanding, nobody did, that Jonathan had tapped into the Spindeltop of New York theatre, triggering a geyser of tolerance and change that would shape a generation of writers and composers to follow.

For me, Rent is a gothic reflection of a moment when our creative community was staring into the face of extinction. It skillfully guides us through the tears of loss and shame to discover humility and gratitude for people we may not even know. Love is the antidote.

But the theatre universe wasn't all in yet. They were only willing to go as far as a brief run off-Broadway.

* * *

Jonathan sounded tired when I called to share the news about White Squall being green-lit. He was happy for me, but I had to temper my excitement because I knew it was hard for him to hear it.

In 1995, it felt to both of us that my career was a quantum leap ahead of his. I'd been working full-time as a screenwriter and documentary filmmaker steadily since 1990, but in reality I was only an inch or two ahead, and unbeknownst to any of us, he was about to eclipse his own wildest dreams in a tectonic way. A whole new life for him was less than a year away. He just couldn't see it.

Jonathan was struggling financially. Everything he had was invested in Rent, but it all seemed so uncertain. Instead of flying to the Caribbean with the cast and crew, I flew to New York. I overnighted at some crappy airport hotel and invited him to come out and spend the night.

Jonathan met me at the curb and helped me hump a couple months' worth of clothes and gear into the back of his beater Datsun station wagon, a car he would leave unlocked on the streets of the city to avoid it being broken into. More than once, he'd found someone sleeping in it.

Belching smoke, he happily delivered me to our digs. As we sat in the bar sipping beers, I remember Jonathan going mental because they had a baby grand piano on a pedestal that was fueled by a floppy disc. It played endlessly into the night, a musical robot replacing an actual piano player. He was outraged that a corporation would substitute a musician with a machine. I couldn't disagree.

We spent the night catching up on everything. I know he was glad I'd come and I could see it had cheered him to talk about the coming drama surrounding the mounting of his play. There were crazy personalities, the money people, and the pressure of dozens of voices in his ear trying to get him to do what they wanted.

It turns out that when people give you money to make your art, they think it buys them the right to inject their opinions. But this is where Jonathan's stubbornness became his superpower. They had no idea who they were dealing with. He collaborated with the few he respected and silenced the rest. We now know it was all going to work out. He knew what he was doing. Then it wasn't so easy.

I had good tidings, however. We needed sea chanties for the movie. A sea chanty is a traditional folk song commonly sung in rhythm to coordinate work aboard large vessels during the age of sail. I referred to them in the script and I figured why not ask Jonathan to write us one or two. It would be good money and a boost, something else to talk about.

I had settled into rehearsals on St. Vincent Island with cast and crew. There was much to do, especially acquainting the young actors to the rigors of sailing a tall ship. And this of course would include learning how to haul away, in unison, in order to raise and lower The Eye of the Wind's twelve massive sails. This would require a song.

Like clockwork, I received a package from Jonathan. It was a padded envelope with the address written in his indelible hand, a cursive script practiced for years, reflecting his love of words. Inside was a cassette tape. I was excited to let Ridley know I had solved the "chanty" problem for him.

But there was a wrinkle. As it turned out, nobody, anywhere, could locate a cassette player. Not even in a car. After a day or two of searching, a production assistant located a stereo system in a bar in neighboring Kingstown.

Ridley and I piled into a car and off we went. The owner of the saloon, an islander with beautiful gold-rimmed teeth, smiled through sleepy irritation of having been woken early and unlocked the door.

It was a total sawdust joint, stinking of molting beer, smoldering tobacco, and the sweet edge of vomit. Cleanup from the previous night's cruise ship patrons awaited the next shift.

The tape player was no easy thing either. It was high on a shelf behind the bar, and our host had to stand on a stool to get to it. Then it dawned on me. Even if the ancient machine didn't chew the tape to bits, I had absolutely no idea what to expect.

The crackly speakers came to life and Jonathan's voice confidently slated the first song. Then he launched into one original sea chanty after another, belting away. I was a little horrified as I'd expected something more polished somehow. Ridley stood there, stone faced, listened to three songs end to end, scrunched his face, and said, "Ya, the first one I think." And that was that.

Upon reflection, all sea chanties are sung generally without accompaniment. They were work songs, duh! It had just sounded a little naked because there was only one voice and I knew the face on the other side of it!

I needed to return home for the birth of our second child, our daughter Tessa. So when they shot the scenes involving the chanties, I was in the delivery room at Cedars-Sinai.

Turned out the actual crew of our ship had work songs of their own and I guess it was easier to use one of those than learn a new one. I didn't realize this until I saw the rushes at Disney and reported the disappointing news to Jon. It was a bummer because I'd told him I thought we were using his song. He was entirely philosophical about it, though, pointing out this was one more thing he'd learned he could do.

Had Jonathan lived, he would have scored the movies I'd later write and direct for sure. Another bitter pill to dry-swallow. Today, that cassette and the songs on it also reside in the Library of Congress. Not bad for music that was rejected. Once again, nobody understood what promise he actually had.

* * *

As that ice storm pounded New York a year later, a purplish review of White Squall appeared in the New York Times by Janet Maslin titled "Seafaring Boys in Stormy Weather". She sought to largely dismantle our labor of love, summing it up as "sometimes listless and tame". Welcome to the big leagues, Mr. Robinson, where they throw fastballs at your face.

I remember sitting in a tiny room at the Soho Grand Hotel, reading that review on the front page of the Arts and Leisure section of the Times. As I leafed through it, I found Jonathan's obituary on the back side of page 1. What?

How could it have been that two college roommates, lifer friends, would share a destiny in the same issue, on the same day, on the same physical piece of paper?! It was a stunning, ironic discovery.

I longed for my pal who I knew would have helped me put it all into proper perspective. But he wasn't there. My friend, confessor, and partner was gone. I could neither share the joy nor sadness of the moment. I was on my own.

* * *

I would experience these feelings when Rent opened on Broadway, when the praise and accolades came pouring in. We were still all in a state of slow-rolling shock. I remember Al, Al's wife Nanette, and Julie looking like deer in the headlights.

Eddie Rosenstein was there with a motion picture camera in hand. He, like me, would take shots at telling Jonathan's story the only way we knew how - through a subjective documentary lens. Unfortunately, those projects were never completed for one reason or another.

There was a groundswell of attention focused on the production. Relative strangers emerged to reimagine Jonathan's life. It seemed peculiar to see the show so big and loud, the protagonist, Mark Cohen, with a spring-loaded Bolex 16mm movie camera in his hands - a camera Eddie and I had both owned. The show was replete with amalgams like that of the people from Jonathan's life, but they were general enough to make direct identification tricky, though many have laid claim.

In the tsunami of mad adoration that was breaking, friends and family were largely swept aside by the rising tide of interlopers, carpetbaggers, and hangers-on. At least that's what it felt like. They were celebrating. We were grieving - are still grieving.

While Jonathan's legend was being written by many of the very same people who had previously rejected and ignored him, it became impossible to separate the man from the story that was being velcroed to him. Those who never knew him were consecrating him.

Jonathan would forever be imprinted with his main dramatic question of "How do you measure, measure a life...?" Now, finally, we could see what he had done. It was an anthem, a triumph, and I felt so proud of him. Everyone did.

Yet there was the awkward duality of joy and sadness for us insiders because we couldn't share and celebrate the moment with him - or later the Tonys or the Pulitzer, any of it.

As the audience roared and speeches were made by the cast - at the massive after-party hosted on the frozen subfloor of a hockey arena, where paparazzi flashes blazed - I felt invisible. We all did - like ghosts in a dream from which we could not awake.

* * *

"Absence and Presence"

I've since had a complicated relationship with Jonathan's work. I deeply love it, but it has also, for decades, forced me to relive my grief repeatedly. So many of the efforts to present Jon's work have been wonderful, and yet they often echo with a distant hollowness I can't quite put my finger on. His absence and simultaneous presence are inescapable.

In any case, we who loved him attend openings in solidarity with the creators, in memoriam of our friend, to share with each performer some intimacy, a personal anecdote or two so that they too might feel closer to the man whose art they are about to inhabit. In spite of the joy and excitement of each of these triumphs, there is a lingering sadness. To endure having that scab ripped open again and again for twenty-six years has been difficult. We all had plans to move forward together, those of us in our geek theatre "tribe", our "Island of Misfit Toys".

We were supposed to raise children and bury our parents together, create, collaborate, argue... go to Mets games and grow old hating the Yankees, and always, always remain the bodyguards of each other's dreams, trusted critics of our separate works, and in the end, be no more or less to each other than we all were in the beginning - those wistful days when everything was possible, when we found our people, each other, ourselves, and forged a collective mission and unbreakable bond of creative accountability and brotherhood.

* * *

Now comes the film adaptation of tick, tick... BOOM!

I braced myself at the Los Angeles premiere of Lin-Manuel Miranda's freshman directing effort about my friend. Sitting near Jon's sister Julie and her now-grown sons, I dreaded reliving the recreated apartment and the Moondance Diner - of going back to the literal physical spaces of a personal trauma. I was afraid it was going to hurt, as it so often has.

But this was not to be. Maybe for the first time since Jon's passing, his work was infused with joy, hope, a lightness of being that was saying everything is still possible in this moment.

I felt Lin-Manuel and Jonathan clarifying the point that, while we have no control over inspiration or the creative impulse, we must endure the bootcamp of survival, preparing ourselves with craft so when opportunity does come, when the stars align, when the muse whispers, we are able to receive her creative caress and let it flow through us.

And if the alchemy of all that doesn't deliver? "You start writing the next one. And after you finish that one, you start on the next... And on and on, and that's what it is to be a writer, honey." The cold, hard truth nobody wants to hear. "But... oh, what a way to spend a day..." Oh, and Jonathan did know what he was about from tick on, for sure. Clearly, so does Lin-Manuel Miranda.

I'm so grateful for that scene in the film. What that agent says to Jonathan is everything. Perseverance alone may not ensure success, but giving up guarantees failure. Endurance is the ultimate test of ambition. We all doubt ourselves. It's human to do so no matter what you do. Jonathan built a creative life, modest to be sure, but that allowed him to continue to develop, fail, and grow until story, skill, and an audience ready to listen showed up. When the door finally opened, he walked right through.

What Jonathan carried under his arm was a message for a generation. He had the functional construct of Puccini's La Bohème, the personal experience of loss and outrage, and the talent, craft, and prep to blend them in the right moment with an answer so relevancy could bless it. I call it poetry.

And for me it changes everything. Contextualizing the irony of his death and the briefness of his life only punctuate and ratify the timeless, universal message he was delivering - time is shorter than we think. Joy is everywhere, open your eyes and look for it. Choose love, not fear.

Lin's tick gets at the core of who Jonathan was with layers and nuance. It is a celebration of hard work and passion - a story about a young man who paid for his triumph by sacrificing his 20s and 30s to toil and labor. He had anxiety, he was uncertain, insecure. But he was unrelentingly dedicated to the mission that had begun with the oath we recited each day at drama school. "First I honor life, and with it, my life in the theatre." He took that literally and his human experience and creative life were rich because of it.

I must also mention a beautifully adapted screenplay by Steven Levenson, a superb cast that includes a flawless performance by my pal Bradley Whitford as the late Stephen Sondheim, and Andrew Garfield, who captures so much of Jonathan - a tour-de-force performance of immersion and commitment, in the opinion of this person who knew every quirky nuance of the actual guy.

It's as if Jonathan slipped inside Andrew Long enough to let us know, me know, it's going to be okay. You see, the thing missing in Rent (for me) is Jonathan. We have to project him onto Mark, Roger, and the rest. But as Ken Burns likes to say of filmmakers, they "raised the dead". Lin and company breathed life back into our brother and now I can forever get a little dose of him whenever I need it.

It is a joyful collage of image, light, sound, the mix, not to mention the music, editing, and pacing are fantastic. I never got ahead of the story, was vexed with dilemmas and surprised over and over - and it was accomplished with the shackles of COVID upon cast and crew. They somehow pressed through and the result is that for two hours, I was back with my friend.

Another well-deserved shout-out must go to Jon's sister Julie Larson, who worked for decades with her parents protecting the integrity of Jonathan's canon of work. She was instrumental in getting tick actualized into the movie we have today.

The film made so many of us who knew and loved Jonathan proud and happy again. I will watch and share this film many times. Most importantly, I KNOW Jonathan would have LOVED it. I'm grateful Lin-Manuel has become such a devoted part of Jon's living legacy. After all, that was always part of the plan - legacy.

* * *

The last time I saw Jonathan was in December of 1995. I was in New York doing post-production on the Wellman film, and he drove to my grandfather's house out on Long Island to hang once we were through. My producer, an athlete turned filmmaker who'd played football at one of the Ivys, was with me. Not exactly a musical theatre guy.

Jonathan and I spent the day walking the beach, throwing a Frisbee, and catching up on all things us. But that night I was exhausted. We had to drive to JFK to catch a super-early flight back to L.A. the next morning. I was cooked after one beer, excused myself, and went to bed. The next morning before it was light, we said our goodbyes in the driveway, got into separate cars, and trailed each other to Sunrise Highway.

The last glimpse I had of Jonathan was of him waving out his window as he peeled off onto the William Floyd Parkway to jump to the LIE into the city. I tracked his familiar exhaust plume until he was out of sight.

My producer and I continued along the South Shore in drowsy silence. After a few minutes, rubbing his sleep-deprived eyes, my companion wistfully remarked, "Interesting friend you have, dude." I shrugged in puzzled agreement. "Yeah. Why do you say that?" "Well," he said, "he kept me up until 3:00 in the morning, singing me the entire score for some musical he's writing called 'The Rent', a cappella! He wouldn't let me go to bed until I'd heard every word of it."

I laughed my ass off. That was the gutsiness of Jonathan. Giving a private performance of what would become the biggest Broadway hit in decades to a perfect stranger into the wee hours. Poor guy had no idea what he'd heard or witnessed. But boy, was he going to find out!

Looking back, it's such a treasured memory and makes me smile to share it. There really was only one Jonathan Larson, and he WAS "the future of the American Musical Theatre". That's not mythology, it's empirical fact. Ask Lin-Manuel Miranda if you don't believe me. He'll tell you the same thing. Jonathan was not going to be denied. He was going to be heard, one person at a time, if that's what it was going to take.

I really miss that guy, my dear friend, the brother I'd never had and all that might have been, and the memories we would have made.

* * *

The final summary in Rob Reiner's coming-of-age classic Stand By Me ends with the words of protagonist Gordie LaChance as an adult writer, reflecting that "I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve... Jesus, does anyone?"

I think the relationships that survive high school are forever linked through the collective, shared memory of childhood. But there is something equally unique about the people we meet in the early years of adulthood when, for the first time, we're independent, or at least separated from the all-too-familiar logic of our parents.

Our histories have been wiped clean as we gather in groups that have joined in common purpose and aspiration. We are flooded with new ideas, new skills, shedding much of what has restricted us, while seeing the world through the ground glass of fresh possibility.

Within that special cohort, there is an even smaller, more intense cadre of true intimates who shape us like no others. At that time for me, one was Jonathan. Today, I can count few men in my life with whom I share that depth of spirit and history.

When it really comes down to who understands me, who I can truly rely upon, be vulnerable with and trust, the club is very small indeed and membership becomes more and more elite and fragile as the years pass.

Jonathan still comes to me in my dreams as does my dad and now Al. Sometimes I return from that place, eyes wet, for the emptier reality I exist in for their having left. But on the other side of consciousness, in that state where I often leave my body and fly, they are all well and content, and I sense they're no longer plagued with the concerns of this mortal plain.

I hope there is an afterlife, a universal collective where we let go of this human experience of our spiritual selves and embrace again in joyful communion. I hope in whatever timeless continuum that is, we may gather along a foaming shore, watching birds fly and the waters run... because we have so very much still to talk about.

Videos