Interview: Composer Iain Bell and Librettist Mark Campbell - A Match Made at STONEWALL (and City Opera)

Iain Bell and director Leonard Foglia.

Was the pairing of Iain Bell and Mark Campbell--respectively, composer and librettist of New York City Opera's (NYCO) world premiere STONEWALL--"love at first sight"? I asked them.

We were at the workshop in New York earlier this month that allowed them and director Leonard Foglia to cross the t's and dot the i's on the opera (and hear the new work performed). We'll finally get a look at the finished product on June 21.

Campbell, the overachieving wordsmith who's now working on his 29th and 30th libretti, answered quickly, "We had no choice but to love each other. It was an arranged marriage by Michael Capasso," General Director of New York City Opera. "Fortunately, it was an easy thing."

Marking anniversaries

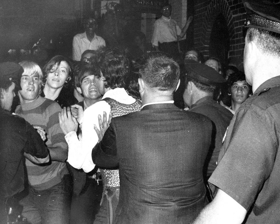

Fortunately? To say the least: The pair had nine months to capture the spirit and feeling, the angst and the triumphs of the events that began on June 28, 1969 at the Stonewall Inn on New York's Christopher Street--widely considered the pivotal moment in LGBTQ history--and make it soar.

New York's Christopher Street.

Why the rush? Simple: Capasso wanted the opera's premiere to mark the 50th anniversary of Stonewall, during Pride Month, while also commemorating the 75th year of City Opera, founded as "the People's Opera" back in the days when Fiorello LaGuardia was mayor of New York.

While commissioning a new work to mark the date in the company's history had been percolating for quite some time, a switch to making it part of City's LGBTQ series--which has included ANGELS IN AMERICA and BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN--to celebrate the heroes of Stonewall made time of the essence. "Once we realized that these anniversaries coincided, the light bulb went on and the choice made itself," said Capasso.

Taking on the project

Not that either of the creators were sitting around waiting for the next project to come in.

Bell was halfway through writing another opera, JACK THE RIPPER: THE WOMEN OF WHITECHAPEL for London's ENO (rehearsing now for a March 30 premiere), which gives a voice to the Ripper's victims. Campbell--whose (R)EVOLUTION OF STEVE JOBS with Mason Bates just won the Grammy for Best Opera Recording--was working on a bevy of new projects, while also getting ready for the world premiere of TODAY IT RAINS. This opera about Georgia O'Keeffe with composer Laura Kaminsky and co-librettist Kim Reed is rehearsing now for its March 28 bow at Opera Parallelle in San Francisco.

They were busy, yes, but neither of them could say "no" to this particular project.

Portraying characters who take a stand

"My first instinct was to say 'yes,'" says Bell, "until I might have to say 'no' because of the timing. 'Let's make this work' I said to Mark and Michael. As a married gay man, the subject matter is of the utmost importance to me. Being able to give these people a voice--their heroism and bravery--is an immense source of pride."

British-born Bell wasn't born until 1980 so he doesn't have personal associations about the event (nor does he remember 1967, when male homosexuality stopped being a crime in Great Britain). "But," he adds quickly, "what I do know about it is that were it not for these people who took a stand and were forced to do what they did that night, I wouldn't be married. I wouldn't be sitting here with a ring on my finger that's a legal representation.

"That to me was the clincher--a debt I owe to these people for their bravery. It is always a privilege as a composer to give something or someone a voice. And when it's something that's as important to our community, the LGBTQ community or any sidelined or disenfranchised group, we can only say yes."

Campbell nods in agreement. "Well, I'll second what Iain said. I wanted to tell this story. When Michael asked if I wanted to do this, I said YES--I don't care what my schedule is. I'm a gay man of a certain age who has survived--who is also married--and I have to tell this story.

Working with the director

"And it was one of those things--a commission where everything came into place very quickly. It was made easier because our director, Lenny Foglia, signed on the at same time as we did. That is a crucial element to any opera--having a director to bounce ideas off."

"I sent him the libretto first before it went to Iain, because I wanted him to spot any problems and he had some great comments that made the libretto much better. So there was no time wasted. We are now at a workshop--we've been here a couple of days--and we're still making changes," he says. "But it was great that, ever since the beginning, we've all been artistically aligned," says Campbell, "including NYCO, Lenny, me and Iain."

(I might add that Campbell is never complacent about his work. I was at a performance in Atlanta of SILENT NIGHT--the Pulitzer Prize winner he wrote with composer Kevin Puts--and the two of them were still taking notes and making changes, after many productions and performances and much acclaim.)

How does it start?

How did it all start? I ask both of them, separately, whether the blank page makes them nervous or gets their motors running? Both had the same response: I love it.

Campbell explains that he likes a large blank page and, in fact, he writes on large newsprint pages. "It's the most exciting thing for me--except for finishing a page and turning to the next one." He adds, " I don't know why it would be terrifying to anyone. It's the most extraordinary privilege to be able to do something like this--to tell a story you believe in, about a historic event that changed your life."

Bell chimes in, "I think of the first day of writing a piece is about all those notes about to be written. I have the same thoughts about turning the page on a calendar for the new year--I think about all those memories yet to be made, all those plans and all those adventures to be had." He continues, "I think the same way about a piece of music--all those notes yet to be strung together, to tell a story, and I love that."

First, the libretto

While Mozart's arch-nemesis (at least as far as AMADEUS goes), Antonio Salieri, said in his opera PRIMA LA MUSICA, POI LE PAROLE--first the music, then the words--I know that Campbell believes otherwise. "Maybe a time will come when it won't, but I'm about to finish my 29th and 30th libretti and every time the libretto has come first," he avers.

"I'm not showing off but that's my experience. I have yet to meet a composer"--and he's worked with many of today's best, including Kaminsky, Puts, Bates already mentioned and Paul Moravec, Ricky Ian Gordon, Julian Grant, among many others--"who can write in a void: They take the cues from the story and the characters." He adds, "And if you're a good composer like Iain is, you give a voice to every different character in a musical way." "That's my favorite bit," Bell chimes in.

What will it be like?

When you're creating an opera at the speed of sound, I asked Campbell, how did you decide what it is going to be like? How fast did STONEWALL come to you?

"The outline for the piece probably came in a two-minute phone call with Michael Capasso when I knew he was going to ask me, 'So what would you do with Stonewall?' So I said, 'Every story has three parts.' I've probably said this too many times: There's the problem, how do we solve the problem, and either the problem is solved or not.

In this case, it was very close to being solved." It was, pretty much, Part I would follow a group of people, Part 2 will be the Stonewall event, and Part 3 will be the day after.

How did the collaboration go from there?

Online introductions

Bell recalls, "We were introduced online and we began Skyping about what was important about this piece: What are the roots, the guts of it? The values we're trying to engage with?

"And we were in exact accordance about what we wished to highlight and that it was very important to us both that diversity was central to this piece. And having those things chiming very quickly in our conversation meant that we knew we were onto a good professional collaboration. It just felt right. There were no obstructions, barriers or askance looks. It all felt very free."

What was it like seeing the libretto for the first time? Does that get your sparkplugs clicking?

"Whenever I do a first read-through of a libretto, I have to make sure I have some time to be calm and still with it, so I'm not speedreading but studying it slowly and carefully," he explains. "My natural gear is a quite energetic one, but I know if I were to rush through the text, I know I might miss things. Pacing myself this helps me pick up on themes, either textual or stage directional."

I ask Bell what's it like working with Campbell?

Says Bell, "It's very easy. I never fear when I see his name come up on WhatsApp, with a question or a thought. What you don't want is someone who always comes to you with problems or creating drama. It's never that way with him. It's always positive suggestions or 'have you thought about...' it's very easy flow dialogue. We both made that very explicit when we first met, 'if you have any ideas, just tell me.'"

Visualizing the libretto

When you're writing your libretti, I ask Campbell, are you seeing it move around on stage as you write?

"Absolutely. I always hear music when I'm working and see what's happening on stage," he admits. "Also, I get up and speak the lines of the character who's singing at a certain time to hear if the voice sounds right, or if a phrase really sounds like it's in the character's language.

"I'm not a librettist who works in an abstract way and then hands it to a director and say 'you figure this out and put it on stage.' I have it blocked out in my mind and I know what's going on. Fortunately, when a collaboration is good, like it is with Lenny [Foglia], the director surprises me with something that's way better than I envisioned. And when the composer is as great as Iain, I get to hear music that's way better than I heard in my head." He concludes, "Yes. that's what collaboration is. It's great when the surprises are nice."

The sound of the opera

So down to the basics with the composer: What is this opera going to sound like? I went onto YouTube and there wasn't much about "Iain Bell 2019," except for a few snippets of RIPPER. Nothing from the other operas he's done--including A CHRISTMAS CAROL, a solo version written for the Houston Grand Opera in 2013. Otherwise, the (gorgeous) music dated from a decade ago, with some song cycles that were recorded by Diana Damrau. (Bell wrote his first opera, in 2013, THE HARLOT'S PROGRESS, for her, including a 25-minute Mad Scene.)

Bell explains, "The wonderful thing about being a composer now is that we're living in a poly-stylistic time; chromaticism and dodecaphony are part of my arsenal--part of what I can call when I need it, as extended techniques on string instruments or percussion or anything that one might consider Cage-ian or Ligeti-an or Berg-ian. Or Sondheim-ian. This is all part of the wealth and fortune of being a contemporary composer.

"I don't believe I need to label things. My music is always a very natural expression and response to what I read and that's what I continue to do. Nothing is calculated. That is, I don't think I want something to sound like 'this'--rather, I respond musically to what I see and feel and that's what comes out.

Lyricism and melody

"But lyricism and melody are always the mainstay of what I do and I hope that people respond to it," he clarifies. "I've learnt from working with some phenomenal singers in the last 10 years just how to write for voices in a way that works with the strengths of the voice, rather than against it.

"Also, atmosphere is really important in what I do. When you hear my music you'll get a sense of place, a sense of time. Is it hot or cold? Are we inside or outside? Those kinds of atmospheric things you'll pick up on."

Let me ask, I say: If someone walks into this room having listened to RIPPER and then listens to this, will they know the same person wrote it?

"Absolutely. Of course, they would, because I'm the same person. I'm joking of course--the pieces were both written in the same 15-month period and both work with voices in a very similar way. What you will notice is the difference in the size of the orchestra, chorus, and the difference in scale.

The sound of 1989?

"I didn't write RIPPER trying to sound like 1888 and didn't write STONEWALL exactly trying to replicate 1969," he continues. "It's 2019, but you can nod at things, wink at things, make gestures that may evoke a feeling or a mood or ambience so you know it's the same composer.

Is there something that sticks out in your mind that says, for example, 'I did this that sounds like 1969 in STONEWALL.'

Bell thinks for a moment and nods, 'absolutely.' "There's a character called Renata who is a fabulous drag queen and we see her getting ready. Though the music is not replicating sounds from 1969, there's a real groove to the bass line of her music that evokes a feeling of time and place."

A less-obstructed landscape

He goes on, "Also harmonically, there's something specific. My first opera, HARLOT'S PROGRESS in 2013 has a 25-minute mad scene and, for me, that called out for a more chromatic, jarring approach in my orchestration because of what we're dealing with. With STONEWALL, it didn't feel like it required that kind of harmonic treatment, so there is a more open, less obstructed harmonic landscape and things fall on the ear a little easier.

"As for what I sound like, specifically, that's something that I can't answer--only other people can," he concludes. Campbell adds, "Iain is a composer who has a tremendous sense of theatre. And drama. And he does it so well."

I ask Campbell about a quote I read, where he said that composers are often blamed for the "tuneless-ness" in modern operas, but he thinks that librettists must share the blame--"because we don't give them organized songs to create tune with." Will we find "tunes" (aka "arias") in STONEWALL?

Repeating a line

His answer? Definitely, adding, "What I meant by that quote is that a tune is often a tune because it's repeated. It's not that one composer writes a tune and another doesn't. It's that a librettist can repeat certain things that allow the composer to repeat them musically, and therefore they stick in the ear.

"Honestly--and I've said this before, too--you can take a phrase from [Stravinsky's quite dissonant] PIERROT LUNAIRE and repeat it many times and an audience will be able to sing it back." (I tell him that I think that is a good trick.) "I really believe that it has to do with repetition. When Steve Sondheim did A LITTLE NIGHT MUSIC, people came up to him at intermission and said, "Finally, you wrote a 'tune'--"Weekend in the Country"--which is such a lie because he'd written so many before. But he figured out that the reason people were calling it a tune was because the phrase "A weekend in the country" is repeated over and over--and that's what they remember.

"So, yes, there are definitely tunes in STONEWALL, beautiful tunes," he explains. "There was one I heard today that will make it hard for me not to weep: The moment in the opera when a character says, 'No, we've had enough. You're not doing this any longer.' It's just powerful. Is it a 'tune'? It is certainly an 'aria'--Verdian. The words are just nothing," he says modestly.

"Raise voices, end oppression"

I pose one final question to the duo: When people walk out of this opera, what do you want them to feel?

Campbell says he wants them to understand that when they join with other people and raise their voices, they can help end oppression. "I know that's a tall order, but this is an example in history of people who had had enough, who were disenfranchised, who had nothing to lose and came together," he explains. "I don't care who threw the first punch, who threw the first stone--none of that. But that these diverse people came together and formed one voice that rose up against oppression."

Quietly, Bell adds, "Thank God for them and people who say 'no.' 'Done.' 'Enough.'"

STONEWALL will have its world premiere at New York City Opera's home at the Rose Theatre of Jazz at Lincoln Center in the Time Warner Center, 10 Columbus Circle at West 60th Street and Broadway. Currently, five performances are scheduled: June 21 at 7:30pm, June 22 at 2pm and 8 pm, June 27 at 7:30pm and June 28 at 7:30pm. See the website for more information and tickets.

Videos